Review

The Wind Keeps Blowing On: La permanencia de las piedras by Federico Pérez Villoro

by Bruno Enciso

Casa del Lago Virtual

Reading time

6 min

Having adopted measures regulating our presence in different spaces in order to address the current health emergency, our relationship with the environment has changed profoundly. Most immediately, it seems that the change lies in having or not having access to certain experiences, those fostered in currently restricted places. Then other types of complexities unfold in various directions: What spaces do I have on hand? What would be convenient, or even possible, to do in those spaces? With whom do I share them? Naturally, experiences around art in the city have been directly altered.

At this juncture, Federico Pérez Villoro presents La permanencia de las piedras (“The Permanence of Stones”), a project commissioned by Casa del Lago, UNAM. The virtual exhibition consists of a short story written by the artist, narrated in the voice of Paula Villanueva Ordás and edited by Isabel Zapata, as well as a series of images by Julieta Gil. Everything is integrated into a website designed and programed by Tyler Dingsun. Upon accessing the site, the visitor listens to an audio recording telling the story of a character who returns to Mexico City and looks for a monument that he knew as a child. While the audio is running, you can navigate an immense white space: rotating in all directions, zooming in or out at will. This space houses different images that operate as plastic landscapes.

The piece is placed within the framework of the pandemic, and it works with the idea of an individual whose interaction with the world is mediated by immense data capture and processing systems, using smart devices. For those of us with computers or smartphones with internet access, it’s easy to feel called upon.

In the story, the character returns to the Mexican capital after a long time. “To return is to realize that nothing is the same” (“Volver es darse cuenta que nada es lo mismo”), he says. His aim is to visit the monument to Rosa Espino in the Calzada de los Poetas (“Poets’ Path”) in the Forest of Chapultepec, so that he can return to a childhood memory that he shares with his mother. Rosa Espino was a fictitious poet that the Porfiriato-era general Vicente Riva Palacio used as an alter ego in order to write and publish poetry without that interfering with his political duties; a secret that the general took to his grave, and that the historian Francisco Sosa would reveal only years later. Once on the path, the character can’t find the monument he is looking for. With the aim of checking whether it’s the correct spot, he goes to Google Maps on his cell phone, but he can't find it there either. If it’s not on Google, perhaps the monument doesn’t exist, or never existed?

Here begins a deep reflection on the intersections of memory, identity, historical narratives, and the information systems that currently shape our idea of reality. Up to the end, the narration continues recounting the adventures of its protagonist, who takes on the task of adding Rosa Espino’s monument to the Google Maps database. The story offers a tour through the painstaking process of becoming a guide in the service of a system that awards points until eventually one can suggest a new place on the map; a stroll through a huge city full of anonymous passages that resist being rendered as hard data. The narrator’s voice is careful in her intonation, and she maintains attention by using a pleasant rhythm. The story is full of generous images and strong critical convictions.

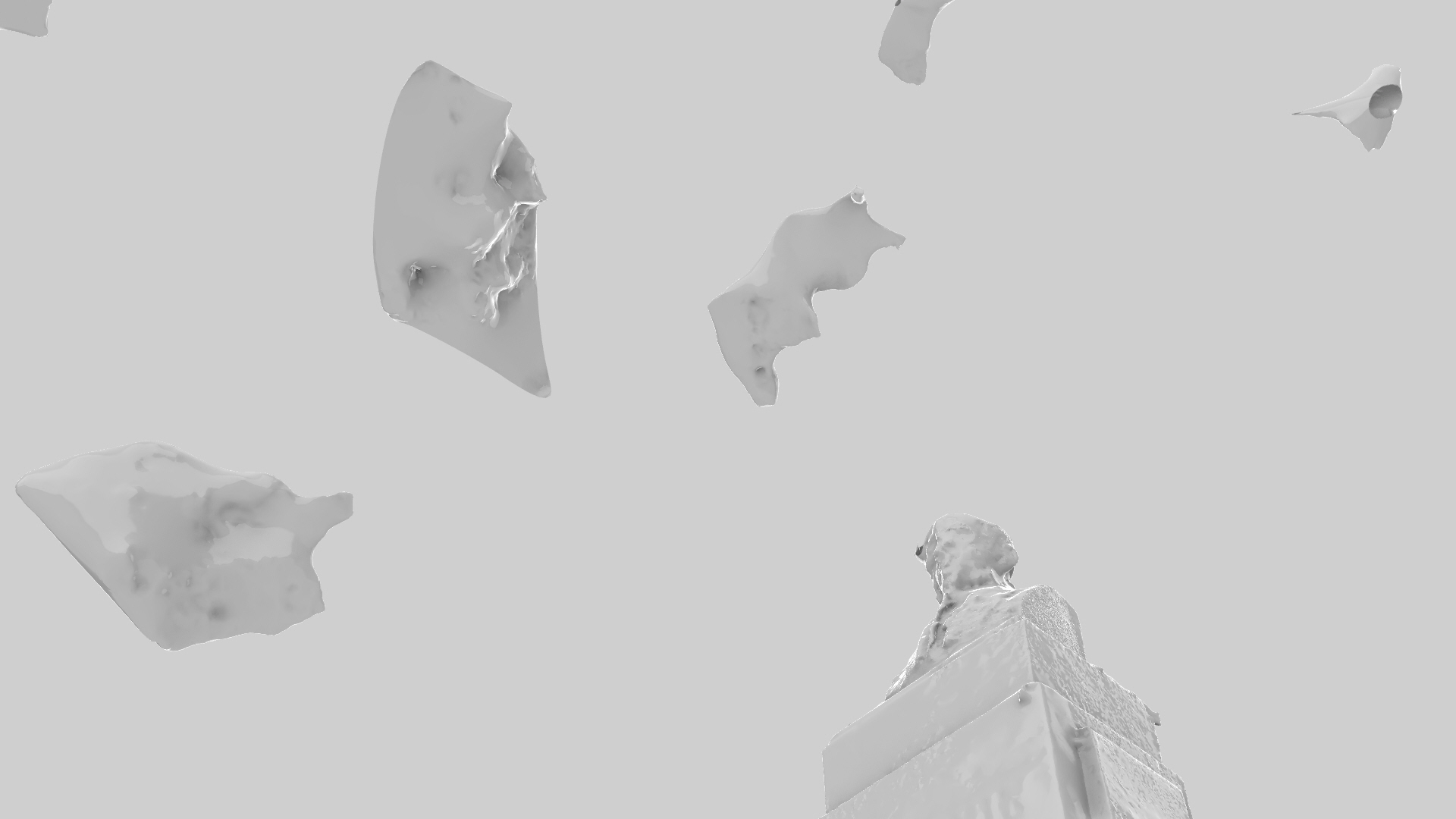

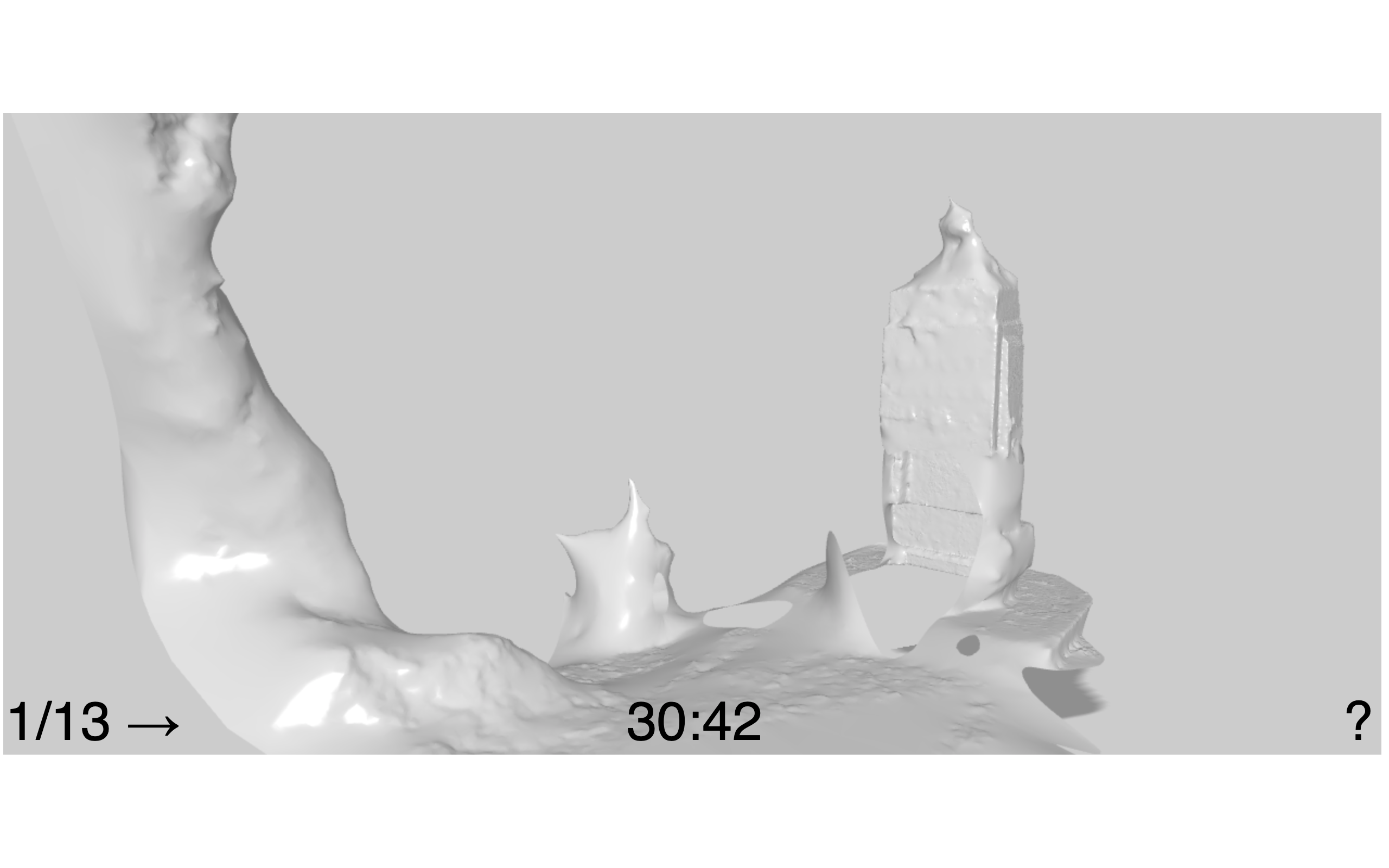

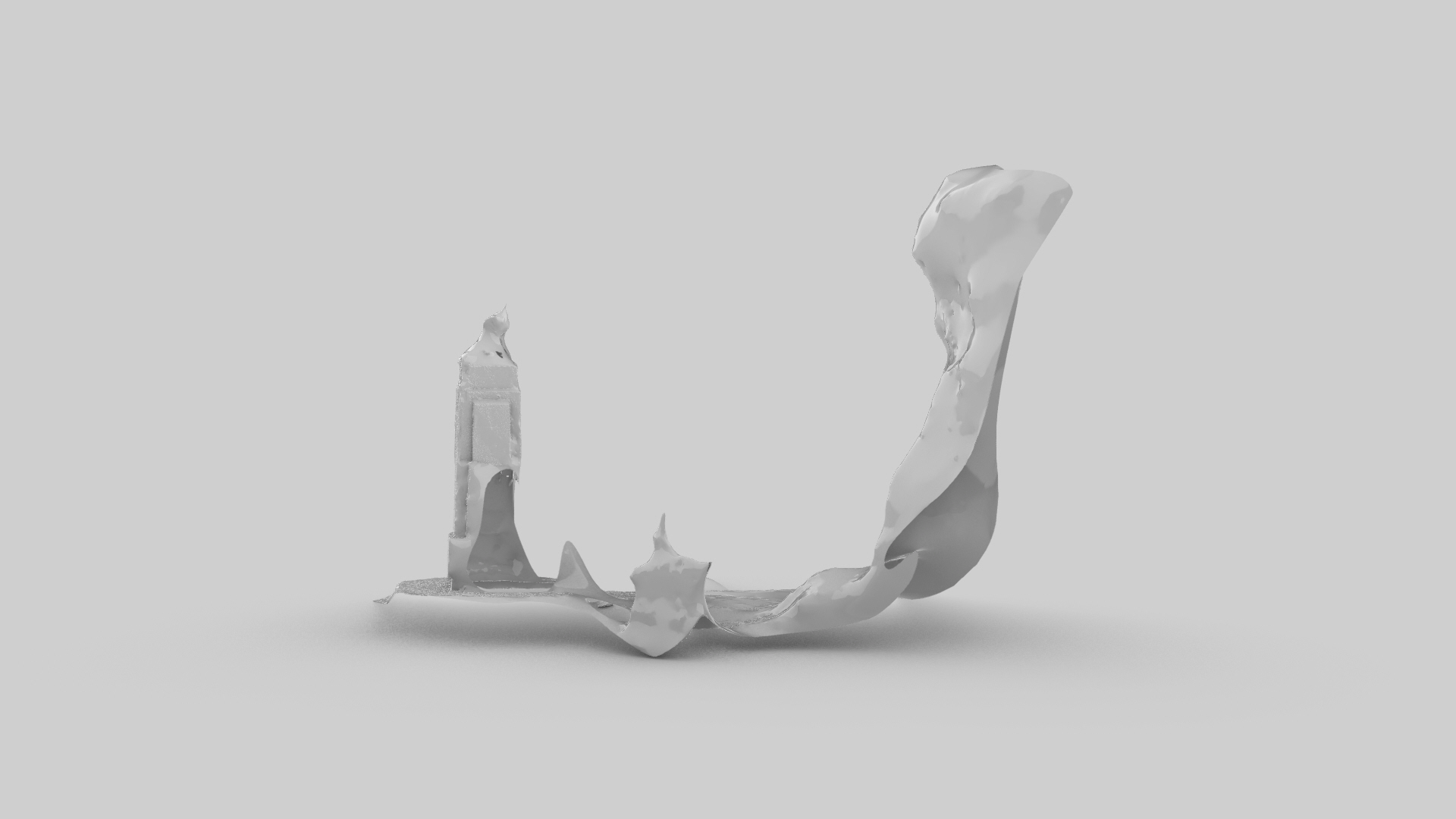

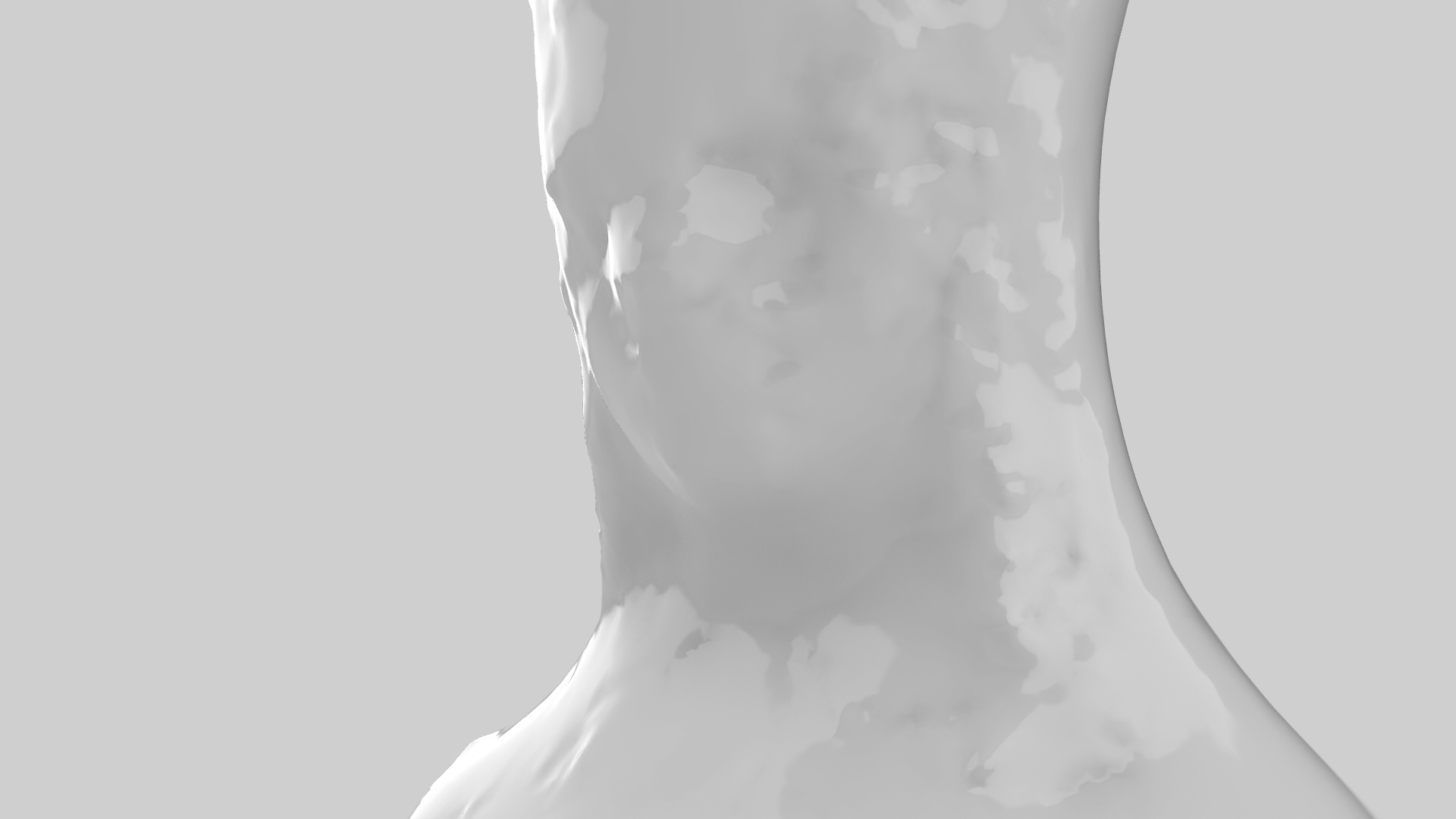

On the website, the visual operation is different. The visitor directs their gaze throughout the space using the cursor, the click function, and, optionally, the keyboard arrows. There are available thirteen images, to be browsed through one at a time. Since the cursor is very sensitive to changes in direction and speed, it may at first seem complicated, but once you have acquired a certain familiarity with it, the different visual and plastic values offered by the images can be explored with ease. All of them offer a variety of material bulks that appear to be made of some type of shiny ceramic. Their white color, their shininess, and the shadows produced by their reliefs make them stand out against the gray background, something so clear that it appears to extend to infinity.

These ceramic landscape-objects were developed from the monuments located on the Calzada de los Poetas. Despite the fact that they seem to unfold mainly on a horizontal axis, there are quite a few plastic variations that leap in all directions. Some pieces of matter lie suspended. These images are an interesting complement to the story’s narration, putting forward precisely a viscous material connection between spaces, memories, and data that circulate on invisible planes. The minimal visual information, fused in the white color, blurs the lines that distinguish the ground from the plants, from the trees, from the monuments, and from those of us who contemplate them.

The story and the images are traversed by a common element: the wind. It’s the sound of wind that, without ceasing, runs throughout the visit to the website. The narration ends, the visual navigation runs out, but the wind continues to blow. It’s not bothersome to the ear, it’s practically white noise; a subtle but very powerful element for noticing a flow that goes on, despite the words and images. A flow that runs throughout a wide space and in a time that is not yet measured.

Even if it’s true that the specificity with which the website operates constitutes a kind of limitation, the joint action of listening to the story and of exploring the images maintains its strength. In addition, it leads to pertinent reflections about the possibilities of works conceived for virtual spaces in the current context. Casa del Lago has announced that this is just the first installment in a series of actions aimed at adding the non-existent monument to Google Maps, so I suggest staying tuned.

Published on June 18 2020