Review

The Persistence of Fascism: On "Estética del dominio" at the Museo Anahuacalli

by M.S. Yániz

Reading time

5 min

Before entering, the Diego Rivera Anahuacalli Museum requires the visitor to shed all ideological prejudices associated with the white cube and its historical role in the Cold War: as a space of “neutrality” for the aesthetic and political deployment of the United States in its struggle with Europe and the rest of the world. The Anahuacalli functions simultaneously as an anthropology museum, a personal archive, a pyramid of worship, and a popular house for cultural encounters. In a space so heavily coded, temporary exhibitions pose a museographic and critical challenge, since one must not only place new objects alongside the thousands already present, but also imagine space where it seems not to exist. The task is one of organizing by subtraction.

Estética del dominio [Aesthetic of Domination,] curated by Arturo Pimentel and Karla Niño de Rivera in the context of the museum’s 61st anniversary, departs from a group of photographs from Germany in the 1930s belonging to Diego Rivera’s collection. The exhibition has a dual intention: on the one hand, to work with the archive of the Nazi regime preserved by Rivera; on the other, to reflect on the contemporary circulation of the aesthetic regime of fascism.

Bringing photographs and works related to fascist ideologies into the museum slightly disrupts its calm and the aestheticized way in which the beautiful pre-Hispanic art collection is usually experienced. I visited the exhibition on a Saturday at midday and noticed the visitors’ bewilderment when encountering the works of the temporary show. It was as if audiences—both national and international—were unsettled by violent images in a space they attended to contemplate beautiful objects, despite the entire colonial history embedded in the concept of the pre-Hispanic. Temporarily, the museum becomes a mixture of times that unsettle affects.

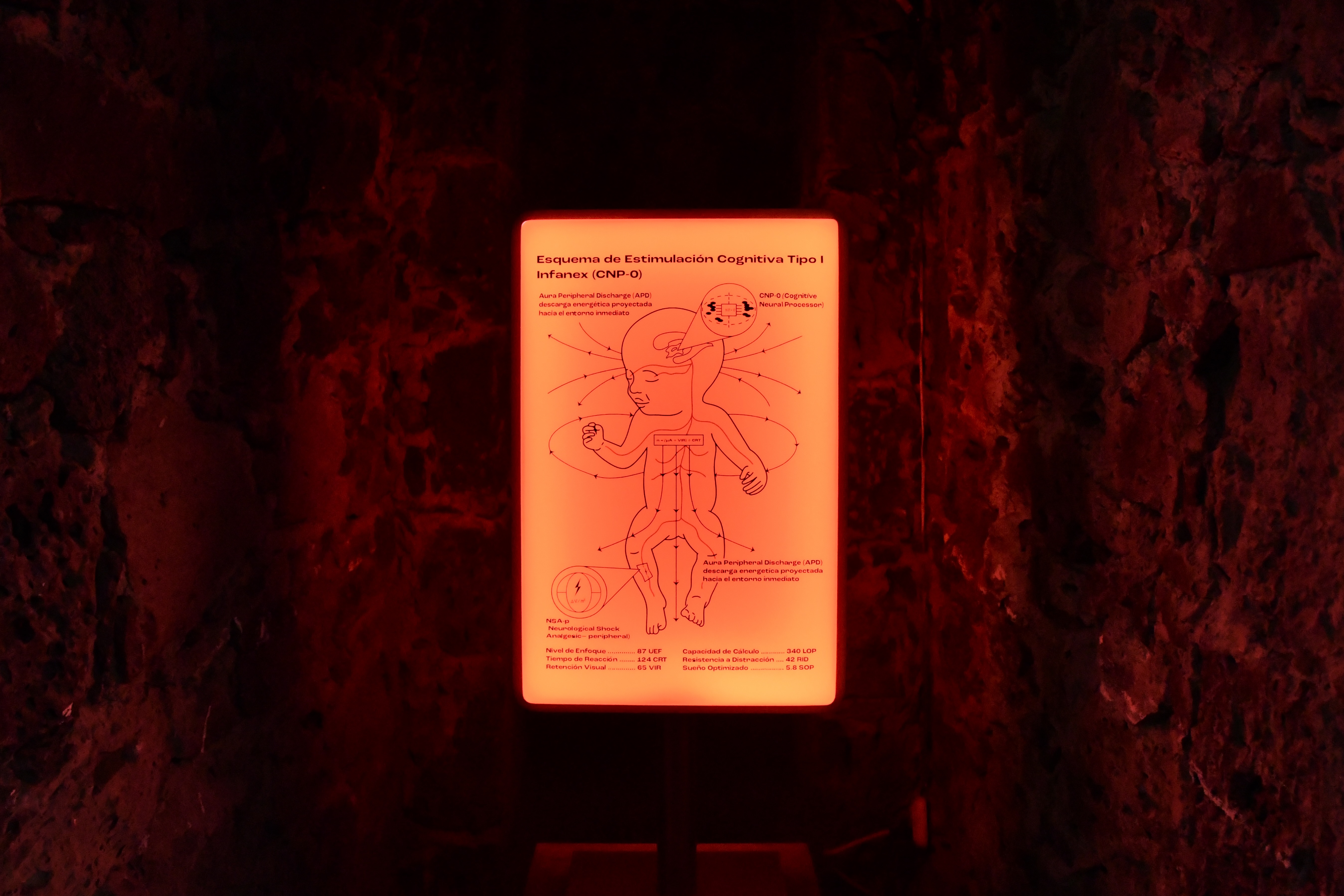

Within the rhythms of the permanent collection, a series of fissures becomes evident upon reaching the cage of Estética del dominio. At the entrance is the curatorial text, but to find the works one must traverse the entire building and carefully attend to material differences in order to distinguish what is art from what is history and heritage. How do ideas and times enter into dialogue here? The exhibition demands crossing the ghosts of pre-Hispanic reverie to uncover images and materials that historically support ideologies and subjugate populations. At first, the tone is subtle: a gridded pyramid with varying opacities announces that historical vision is fragmented. Then appears an extremely strange, glossy, and beautiful diagram by Gabino Azuela, Esquema de estimulación cognitiva [Cognitive Stimulation Scheme,] which promotes a cerebral implant to enhance cognition. Azuela transported me to science fiction and to the idea of fascism as an aberration in history, a collective delirium. I recalled the series El Hombre en el Castillo [The Man in the High Castle,] based on Philip K. Dick’s novel, in which the world is different because the Nazis won the war; the resistance encounters scattered films containing fragments of a liberal world led by the United States (our own). The narrative opens the hypothesis of an inverted world, in which reality itself is also an implant in the collective brain—much like in Azuela’s piece.

At the center of the exhibition, on the second floor, stands the cage in which the Nazi-regime photographs preserved by Rivera are displayed. Alongside them are engravings and images from antifascist movements and caricatural denunciations. In this dialectic, the aesthetic of domination becomes palpable as the use of collective bodies.

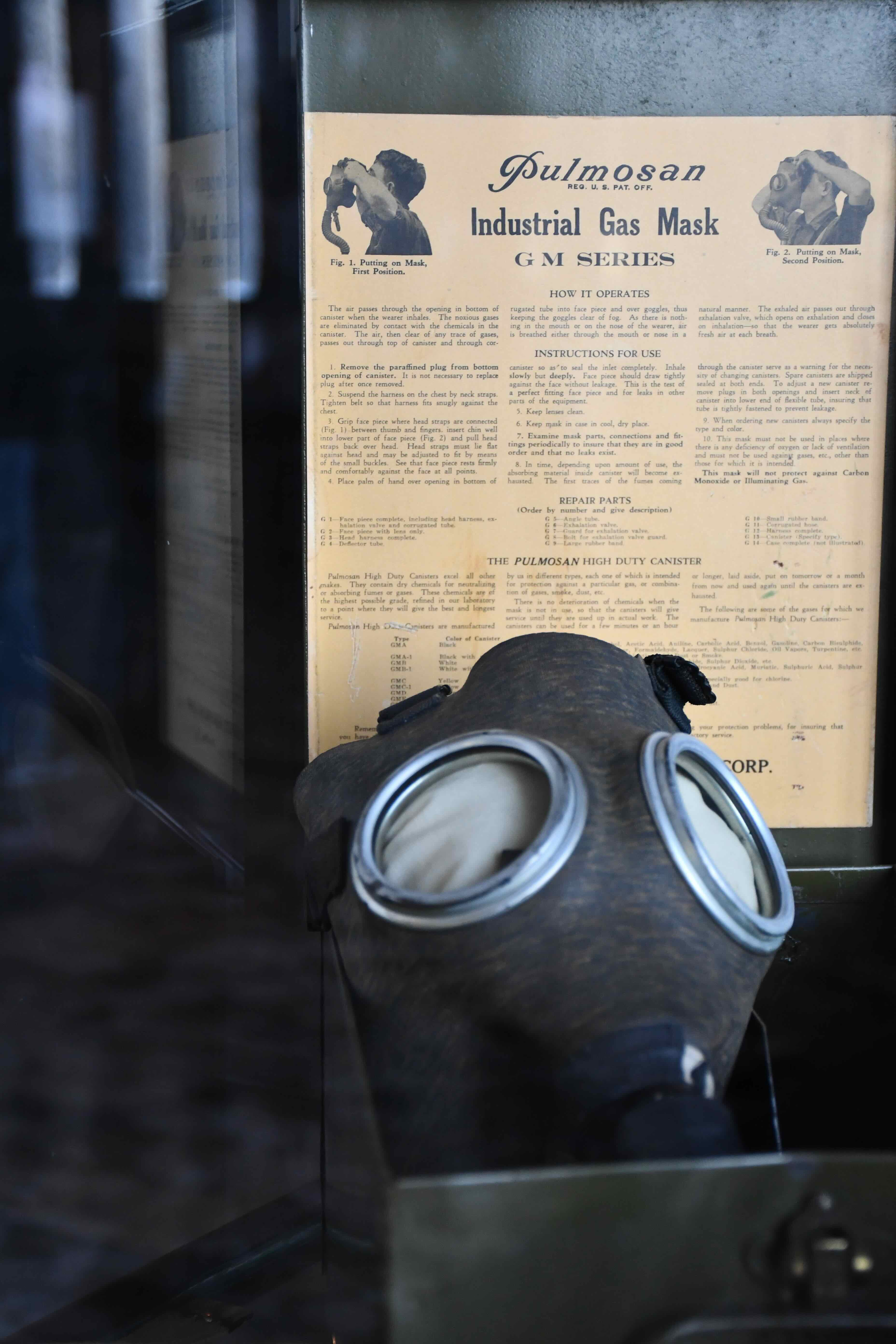

Next to the cage is a gas mask that Rivera used several times in his murals, as if it were necessary to place an index of reality next to the images in the exhibition, as if representation alone were insufficient to display fascism in its brutality. On the other side of the cage stands a poetic planter that unsettles the historical materiality of the exhibition. This planter is part of Iván Argote’s Flores Silvestres [Wildflowers] series. In it, the artist rescues fragments of the bases of historical bronze figures and, by slicing them, fills them with local flora that slowly dies, suggesting that even great names and their histories are transitory, and that not even the most atrocious violence survives the cycle and beauty of the wildest plant.

The exhibition unfolds through oscillations between history as to what truly happened and the materialist poetic gestures of artists who flee ideological reification. I believe the success of exhibitions drawn from collections lies in presenting the past not only as it actually was, but in reactivating the ghosts that pursue us. Because, ultimately, to curate is to become the ghost of others’ ghosts; it is to pursue spirits that may not wish to return. We become hunters of an inactive memory. And it is there—when we strain time—that history reveals itself as an accumulation of material affects that crash against the constitution of the present.

In one of the second-floor rooms there is a video of a woman running with all her strength away from a war tank. This piece was the one I noticed most unsettled viewers. It is evident that the video is staged: the tank is not aiming at her, nor is the woman truly trying to escape. In the background there are trees she could hide behind, but she does not attempt to do so. The audience’s frustration grew as it became clear that the woman was not actually fleeing, but running in circles. The video is by Regina José Galindo. She is shown running in Kassel, the main arms-producing city during World War II. Perhaps what this piece reveals is that, unknowingly and unwillingly, we are all acting as if we are fleeing fascism without knowing how to truly escape it—or whether we want to. Because unlike the 1930s, today we do not know which war tank announces its arrival.

Translated into English by Luis Sokol

Published on Jan 4 2026