Essay

The Arts of Monoculture and Care in Art: "Espacio vientre" by Delcy Morelos at the MUAC

by José Imanol Basurto Lucio

Reading time

7 min

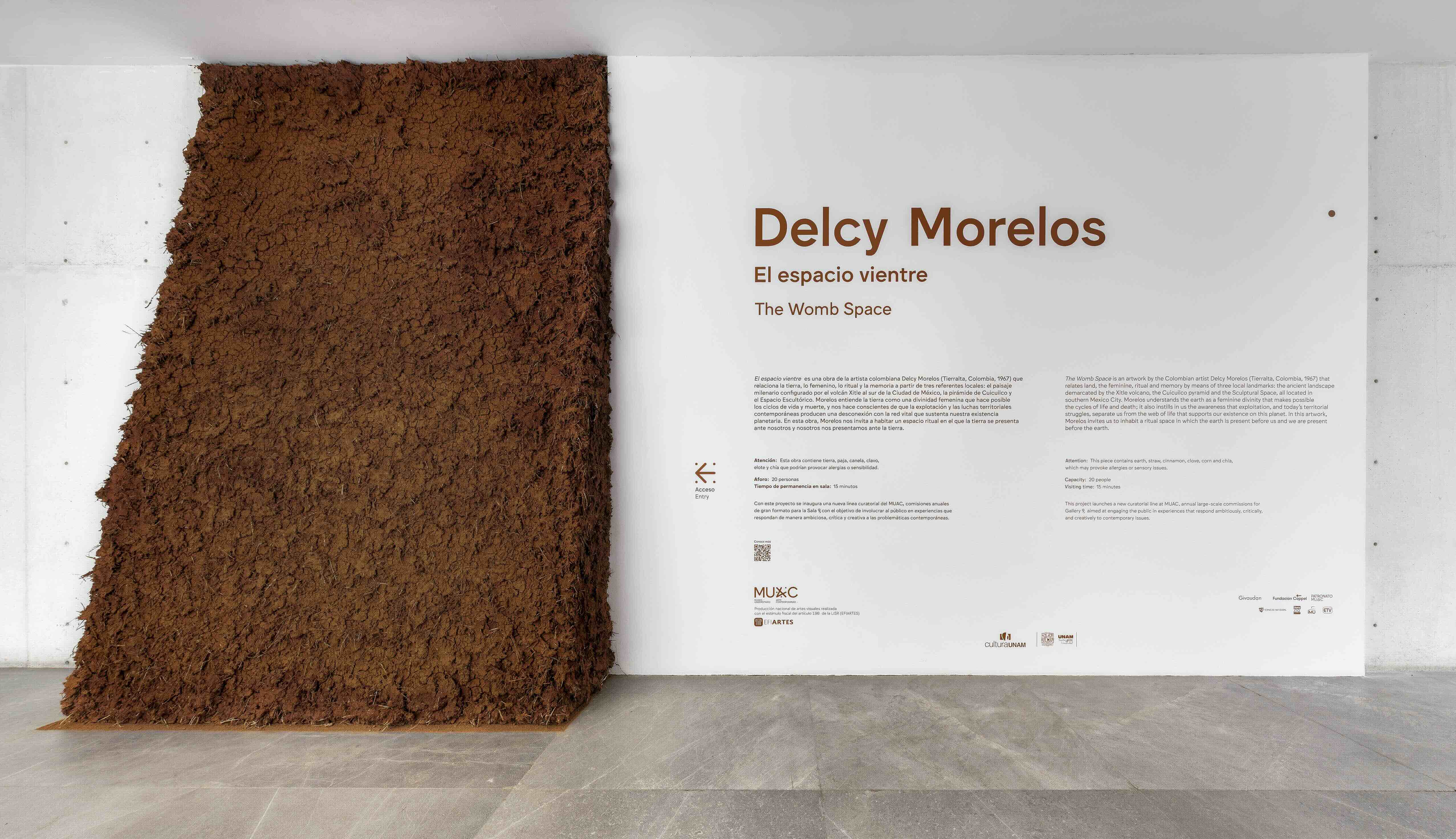

Espacio vientre by Delcy Morelos, at the Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC), proposes the possibility of a gentle relationship with the earth. The exhibition is a site-specific installation produced through a series of visits by the Colombian artist to Mexican territory. Curated by Daniel Montero and Alejandra Labastida, the project presents itself as a declaration of intent in the face of planetary crisis, renewing a debate on the entanglements between soils, humans, and ecosystems.

To enter the installation, visitors pass through a tunnel that leads them to the center of a set of concentric, stepped terraces. Space frames the earth as a feminized and fertile entity. Upon entering, one feels a sudden shift in temperature: a current of cold air covers the skin. Taste and smell adjust to register the subtlety of an earthy flavor that modulates as one moves through the installation. Vision is drawn to details that reveal variations in the multiple (re)arrangements of the substrate and its plants. The visitor is surrounded and overwhelmed by an entity that breathes and displays its force through diverse sensory channels.

Despite its good intentions and its attempt to activate a different aesthetic regime, Espacio vientre participates in the logic of monoculture: its installation reproduces an operation of domination and disregard for the non-human agencies at play. Monoculture is an agricultural-industrial practice based on the exploitation of territories for the standardized production of high-demand crops. This method tends toward the homogenization of heterogeneous ecosystems: plants, soils, organisms, and human bodies inhabiting the land are reduced to interchangeable commodities—docile, stripped of singularity, and redeemed only through a human will that asserts power over them.¹

Delcy Morelos draws, within her visual repertoire, on references to the archaeological site of Caral in Peru. However, her concentric terraces also recall another Andean site: Moray. Moray was an agricultural infrastructure that employed terraces and raised fields to produce diversified crops arranged at different levels.² Such polycultural practices continue today through a long-term, dynamic process in which ancestral and Indigenous–peasant knowledge³,⁴ are activated. Under these conditions, relationships with territory are negotiated: temporalities and the needs of the various agencies involved in cultivation are articulated.

In Morelos' installation, discursive absences appear to downplay the importance of the non-human bodies with which the artist collaborates: soil and plants. First, an unconscious monoculture is enacted. Espacio vientre already appears to host timid sprouts of what seem to be chia plants. If so, the botanical richness of Andean raised fields has been replaced by the homogeneity of a single low-maintenance species, whose seeds participate in an industrial, transnational commercial network.⁵

Second, it is presumed that the lighting and humidity conditions of the gallery are not “regulated” by the museum’s artificial ventilation and lighting systems. It remains unclear whether the needs of the soil are expected to be met solely by the faint sunlight filtered through the ceiling skylights. Given that this is a fragile ecosystem inhabited by plant species and bodies of soil, the exhibition’s discourse should address these practical and concrete matters concerning the well-being of the whole.

During my visit (two weeks after the opening,) I found the mounds dried out and gradually crumbling.⁶ The wall texts do not specify whether a watering protocol will be implemented to maintain their firmness and prevent erosion. What is stated is that the installation was made using fertile soil previously used for maize cultivation in a nearby community. That community remains anonymous within the discourse; its name is not mentioned. This information would be crucial should a process of returning the soil take place. Even so, uncertainty remains as to whether the substrate will still be usable after nine months of what appears to be negligent treatment.⁷

In the face of the emergence of artistic projects that sow life within the inhospitable terrain of the museum, comprehensive intervention protocols are required—protocols that respond response-ably to the more-than-human entities that encounter one another in the gallery space. These protocols must be named in the discourse; otherwise, a form of low-intensity domination is performed. It is paradoxical, given the installation’s own aims, to stage a commentary on human–soil relations while simultaneously ignoring the needs of the soil and the plants already germinating within it. These are not inert objects displayed for contemplative viewing, but agencies/subjects that co-produce the aesthetic experience and require care for their subsistence.

A question of care in art is beginning to germinate. When the needs of non-human participants in artistic processes are disregarded—as occurs in Morelos’s installation—an art of monoculture is produced. That is, homogenizing and sovereign processes that manipulate other bodies are reinforced. In this case, the art of monoculture treats plants and soil as inert, docile materials, available to be intervened upon, shaped, and exhibited without consideration for what they require in order to thrive.

We know that plants and soils are not inert materials, but creative agencies. In botanical science, discussions now address the cognitive faculties of plants; Stefano Mancuso has developed scientific research protocols to establish such capacities. To preserve their vitality, plant organisms deploy strategies of reading, intervening in, and deciding upon their ecosystems—they become agents.⁸ Something similar occurs with soil. Laura Tripaldi questions the presumed inertness of these materials by pointing to their “intelligence,” present in their physicochemical recursivity. This allows them to operate as self-organizing systems that perceive and respond according to environmental conditions.⁹

In Espacio vientre, a material-objectual rhetoric is enacted that eludes human responsibility for sustaining the delicate relational ecosystem produced within the framework of the artistic installation. This observation, however, should not be read as an act of public shaming, but rather as a suggestion that knowledge about care in art be allowed to flourish. Insisting on care is not synonymous with imposing a moral imperative or performing punitive surveillance. It is, instead, an invitation to sustain ethical uncertainty within discourse.

A provocation, then: it is possible to inhabit and represent the vertigo of not knowing whether one is doing enough for the agencies summoned by a work, and still attempt to care for them. This would entail naming procedures and making visible the (collective and individual) efforts deployed to ensure the well-being of the non-human collaborators who create alongside us. It is a matter of practicing—and insisting upon—other arts that are increasingly just, that disobey sovereignty over the non-human and resist the logics of monoculture.

— Translated into English by Luis Sokol

1: Cfr.: Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World (Princeton, 2021), 38-40.

2: S. R. P. Halloy, R. Ortega, K. Jagger y A. Seimon, “Traditional Andean Cultivation Systems and Implications for Sustainable Use,” Acta Horticulturae 670 (2005): 12. 31-55.

3: Elvis Parraguez-Vergara, Beatriz Contreras, Neidy Clavijo, Vivian Villegas, Nelly Paucar y Francisco Ther, “Does indigenous and campesino traditional agriculture have anything to contribute to food sovereignty in Latin America? Evidence from Chile, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Guatemala and Mexico,” International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability (2018). DOI: 10.1080/14735903.2018.1489361.

4: Francisco Javier Rendón-Sandoval, Ana Isabel Moreno-Calles, Perla Gabriela Sinco-Ramos, Mariana Vallejo, Luis Felipe Arreola-Villa y Alejandro Casas, “Peasant’s Motivation for Managing Plant Diversity in Traditional Agroforestry Systems from the Tehuacán Cuicatlán Valley, México,” en Biodiversity Management and Domestication in the Neotropics, ed. Alejandro Casas, Nivaldo Peroni, Fabiola Parra-Rondinel, Veronica Lema, Xitlali Aguirre-Dugua, Edna Arévalo-Marín, Hernán Alvarado-Sizzo y José Blancas (Springer Nature Reference, 2025), 2-3.

5: It is difficult to identify the plant species, however, this is how it was referred to by an educational facilitator at MUAC. The possibility that these are chia plants is high, considering the appearance of the sprouts and the artist's history, as she has used such seeds in other installations. See: Delcy Morelos, “There has been a dictatorship of vision in the visual arts,” interviewed by Mariana Toro Nader, Ethic, June 18, 2024. https://ethic.es/2024/06/entrevista-delcy-morelos/.

6: This was pointed out by a custodian, who warned me not to get too close because there had been previous incidents with sporadic collapses.

7: The exhibition will be on display until July 7, 2026. Its nine-month duration alludes to the length of pregnancy.

8: Cfr.: Stefano Mancuso y Alessandra Viola, Sensibilidad e inteligencia en el mundo vegetal (Galaxia Gutenberg, 2015).

9: Laura Tripaldi, Mentes paralelas. Descubrir la inteligencia de los materiales (Caja Negra, 2023), 134.

Published on Feb 8 2026