Review

The Work of Art in the Age of Branding: On "Superarme" by Andy Medina

by Stefanía Acevedo

At Galería Galería

Reading time

7 min

Superarme by Andy Medina (Oaxaca, 1993) opened on December 19 at Galería Galería. The show is an investigation into intervening in logos and trademarks, taking them as part of a contemporary symbolic language in which desire and fetish are at play, as well as an investigation into tactics for appropriating those brands that are inacces$ible to us.

In Superarme, Medina has focused on the complex process of “branding,” that is, the process of advertising and positioning a brand until it’s established as a symbol in the culture: everything can potentially become a commodity so long as it bears that logo. In this exploration, Medina refers to Supreme, known for taking the aesthetics of skateboarding and streetwear to levels of minimalist design that have established it as a cult brand. Its “branding” makes anything bearing its logo a commodity, from bricks to pipe wrenches. I had the opportunity to talk with the artist about the exhibition:

For this exhibition it was very important to link the profiteering of the fashion world to that of the art world. What makes Supreme valuable is the profiteering around the brand. This same mechanism takes place with art; art pieces function under the same paradigms.

Medina uses the brand’s visual elements to offer a twist on branding strategies, and in two registers: on the one hand, he critiques the economic system that fetishizes these products; on the other hand, he makes use of it by inserting it into the contemporary art circuit as part of the pieces’ value. In Medina’s words:

I’ve seen a lot of pirating of Supreme and it struck me to see how such an expensive brand has a copy, undifferentiated from the original. They both have the same image. The pirating of a brand as prestigious as Supreme is in some way aspirational, since people without access can’t buy such expensive clothes, but they devise their own methods of adaptation in order to have a garment.

Hence the show carries the title Superarme (“Exceeding Myself”), referring to that aspiration characteristic of every success narrative. Medina harnesses logos and he exploits the value developed by marketing in order to enter into an economy of images from existing records.

Appropriating the Supreme logo and bringing it to his own production implied that Medina would change, to begin with, the brand’s characteristic red color for the electric blue that has accompanied his work and that is coming to be his own seal. A blue background and white letters make up the color palette of Superarme and of almost all his pieces. The entire room at Galería Galería was painted electric blue, which contrasts with the impeccable white of the floor; one had to enter wearing cloth shoes in order to keep it in that condition. Medina made his own curatorial and assembly decisions, thanks to his previous experience at Yope Projects and La Trinidad, galleries in Oaxaca.

The ethos of contemporary life is to “exceed oneself” through money, since that seems to be the only way of quantifying success. In that sense the piece most critical of this notion of progress is a photo printed in black and white on tarp, of a supply-center diablero (cart-carrier), bearing a huge smile, showing us his arms as both tools and as fruits of his labor, with the Superarme logo above him. With this gesture Medina reminds us how the discourse of success operates at different levels, as well as that his work is far from any romanticizing of precarity. In the future the artist would like to use this piece to promote his brand on a billboard. Superarme is thus the launch of Medina’s brand, through which the circulation of his own production will begin.

As is characteristic of the artist’s work, a picture is presented using the pigmented marble plaster technique, in this way appropriating the tradition of Oaxacan painting that he inherited. In this picture the marble plaster is electric blue with a white background from which emerges the fragmented brand Super / arme, the edges surrounded by mirrors. On the floor we find several Superarme decals that seem to indicate the appropriate distance for correctly observing the pieces. On the ceiling there’s a giant sticker covering the entire white surface. Superarme on the ceiling and on the floor—it’s everywhere!—a bombardment so you never forget it.

Among the other pieces are branded silver knuckles, which sit on a triangular white base mounted on a wall. These are presented as accessories on an acrylic base, allowing one to see them in their entirety thanks to the half-moon mirror behind it. The piece’s intrinsic value, what it bears thanks to its material, is augmented in a contemporary art branding environment.

The second picture contains 36 pins embedded in a background of acrylic blue paint and white lettering. The fragment shown in this piece is “Sup”: the pins in some way reproducing the painting itself by having a blue background and white letters, fully showing the Superarme brand. We observe commodity upon commodity in a gesture leading Medina to experience the materiality of painting itself.

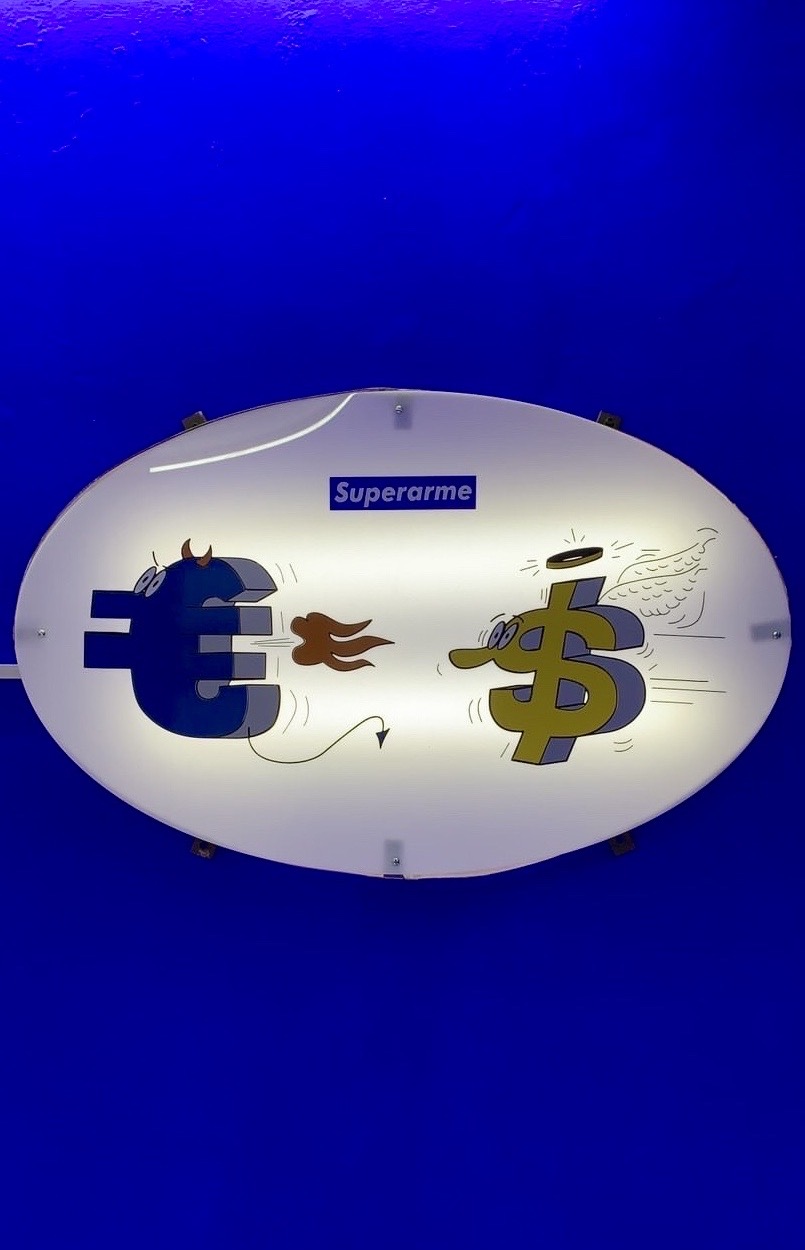

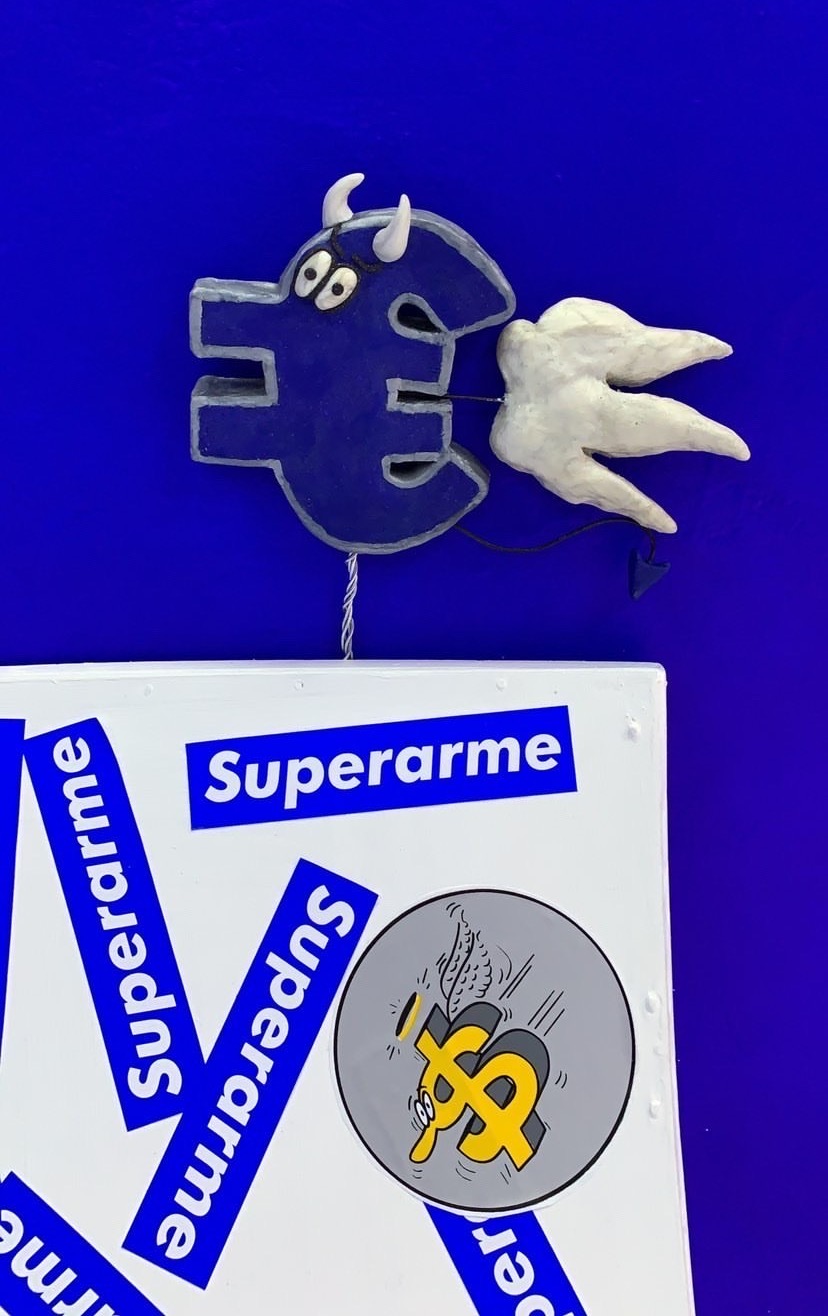

There’s also a virtual correlate of visibility that, like any brand seeking to position itself, is played out on Instagram. Medina created accounts for Superarme (@s.u.p.e.r.a.r.m.e) and for 0nly_cash (@__0nly_cash__), a project on which he has worked for two years and in which he carries out explorations with graffiti and drawing. From there emerge characters guided by comic aesthetics like innocent Cent, grandfather Dollar, little angel Peso, and little devil Euro. With these characters Medina has aimed to delve into his research on how the market works without abandoning irony or humor. We find some of the same characters in this show, as in an acrylic light box where we see Euro and Peso accompanied by the Superarme logo.

We also find a small installation evoking the world to which Supreme is directed: skateboarding. A wooden ramp displays the logo, as well as Euro and Peso, who stand at the top as small polymer clay sculptures with which the artist has begun to explore the concept of the art toy. The transition between fashion accessory and art piece is dissolved in these works as well as in the knuckles.

Medina’s work veers toward “culture jamming,” a popular practice of intervention in logos, but also toward reflecting on the reproduction of the work of art in a copy of a copy of many copies. He reminds us that there’s no original to which we can return, and—if there is one, as commercial brands claim—it must be desecrated and pirated. In reproduction and copying, we break with the auratic or original object that would seem not to admit any copy of itself. Fortunately, we can break the aura surrounding the original object. Exactly that characteristic of the copy—that is, its being repeatedly updatable—forces us into continuing to wager on that change in the fields of visibility. We will just have to wait for a meta-appropriation in which someone pirates Superarme.

Find more info about the show here.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

Published on January 9 2021