Review

Peninsula sowing: On 'Tierra de pocos. Teatralidades y farsas' at Pequod Co.

by Dorothée Dupuis

Reading time

4 min

It’s said that in 2007, in New York—at the speculative peak of the U.S. art market before the subprime¹ crisis—gallerists fought to be first into the graduate shows at Parsons, Cooper Union, or Columbia in order to scout the most promising artists and invite them into their programs for the following year.

In Mexico City, despite the impact of a program like SIEMBRA—initiated by kurimanzutto gallery in the middle of the pandemic, which definitively put a generation of artists such as Ana Segovia, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane (both soon incorporated into the gallery’s roster), Wendy Cabrera Rubio, or Paloma Contreras Lomas (represented, in fact, by Pequod Co.) on the map—the group-exhibition format for introducing young artists remains rare among local galleries.

This is why the joint initiative of Pequod Co. and Proyecto Y² to present Tierra de pocos. Teatralidades y farsas—showcasing the work of four recent graduates from the University of the Arts of Yucatán under the curatorship of Lorena Peña Brito, chief curator of the Museo Cabañas—stands out within the local art season’s opening landscape.

The exhibition invites viewers into key issues of the Maya peninsula: persistent poverty; the exoticization and invisibilization of local identities; and tourism’s logic of dispossession and extractivism applied to land, nature, and people. These realities, though obvious, merit our attention—especially because of the original ways the works approach them. It also bears witness, in the work of artists so young they were born after 2000, to a completely naturalized understanding that gender is a construction and that, while the binary still needs to be fought, it is no longer taken for granted.

The piece that immediately caught my eye was Melissa Gabriela Aguilar’s video El andar de la obra negra, la alteración de los paisajes (2024), in which the artist slowly builds herself high-heeled sandals out of rubble. The work alludes to an architectural landscape where the concrete block can signify both the intense real estate activity and the precariousness that continues to govern most residential areas, as well as the pain bound up with both. There’s humor and a kind of pride in this performance, referencing canonical feminist art in a good way; that humor is also present in Aguilar’s other video La persecución de la Yaguara (with Mónica Mitre, 2025), whose queer/TikTok vibe effectively pokes fun at the exoticization of Maya symbols.

Ximena Carrillo’s video-actions Gota #1: lágrima and Gota #2: tortura (2025) recall canonical video art through their classic framing, simplicity, and execution. The piece recreates the figure of La Lloronathrough the artist’s own youthful face, at once source and path of tears. Exposed to the extreme, her dampened visage—as Peña Brito’s curatorial text notes, sweat serves as a common thread across several works—conjures both Abramović and Miley Cyrus in Wrecking Ball, a mix of references typical of her generation.

In Max Castañón’s work, sweat becomes even more visible: the artist uses boxing (which he has practiced for years) as a living metaphor of a masculinist yet homoerotic obsession with the male body and its limits. Boxeando contra su sombra (Sombra, 2025); stealing athletes’ underwear in gyms to stuff a punching bag that, in my imagination, could be both hit and hugged (Intimidades, 2025); or directing a chorus of half-naked young men skipping rope like a classical coach (Orquestra de cuerdas, 2025)—all allude to the constant eroticization of a tropical climate instrumentalized by vacation culture and its capitalist wellness ethos, with a queer ambiguity that is formally strong.

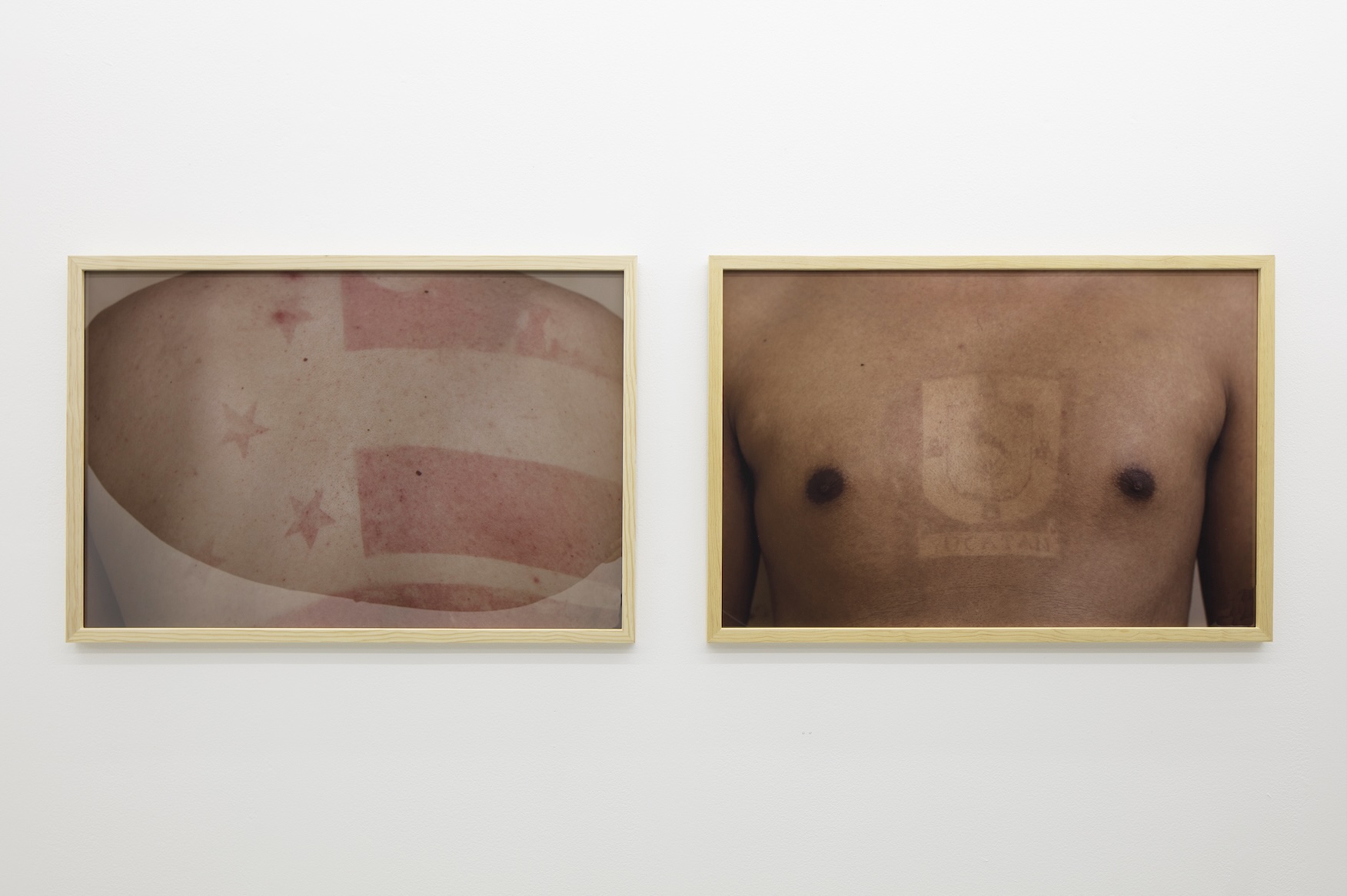

Finally, Yael de Gorostegui’s work explores Yucatecan flags and symbols (Series: Lo que revela el sol, 2025) imprinted on the skin of models after hours of sun exposure. This stencil-like system also relates to her aquatint and etching practice, visible in her more abstract plant-motif prints. Although at first I felt a little cold toward the apparent literalness of the work, I ended up seduced—as with the other artists—by the classicism of her stagings: frontal photographs that, in an age of AI, eschew theatricalization—contrary to the show’s title—and instead show things as they are: like the cruelty of the Yucatán sun, which crushes everything.

— Dorothée Dupuis

Translated to English by Luis Sokol

1: Subprime refers to high-risk loans granted to borrowers with poor credit histories or low incomes, which increases the likelihood of default.

2: Proyecto Y is a platform for the development of emerging art from Yucatán and Quintana Roo, led by collector Catherine Petitgas, artist Fritzia Irízar, and manager Óscar García.

Published on October 2 2025