Review

Evidence of a Suspicion: On Dulce Chacón’s Paleontología Sideral at Banda Municipal

by Jimena Cervantes

Reading time

6 min

The Banda Municipal gallery presents the exhibition Paleontología Sideral [Sidereal Paleontology] by Mexican artist Dulce Chacón, curated by fernanda ramos mena. Upon entering, I get the feeling of visiting a science fiction museum or standing in front of a cabinet of geological curiosities from an indistinguishable past-future. Paleontología Sideral showcases the development of a long-term investigation complemented by another project by the artist, Los objetos que caen del cielo [The Objects That Fall from the Sky]. The research-fiction stems from an archive of images, observations, and tracking of fallen and found objects. The artist focuses primarily on the record of space debris and meteorites found near the Rincón del Paraguero crater in the Valle de Santiago, Guanajuato. From these records, a series of questions unfold regarding the implications that her findings have triggered on different scales of human life. This artistic research exercise strains the relationships between information and visualization within the frames of interpreting scientific and historical facts when speculative elements are involved.

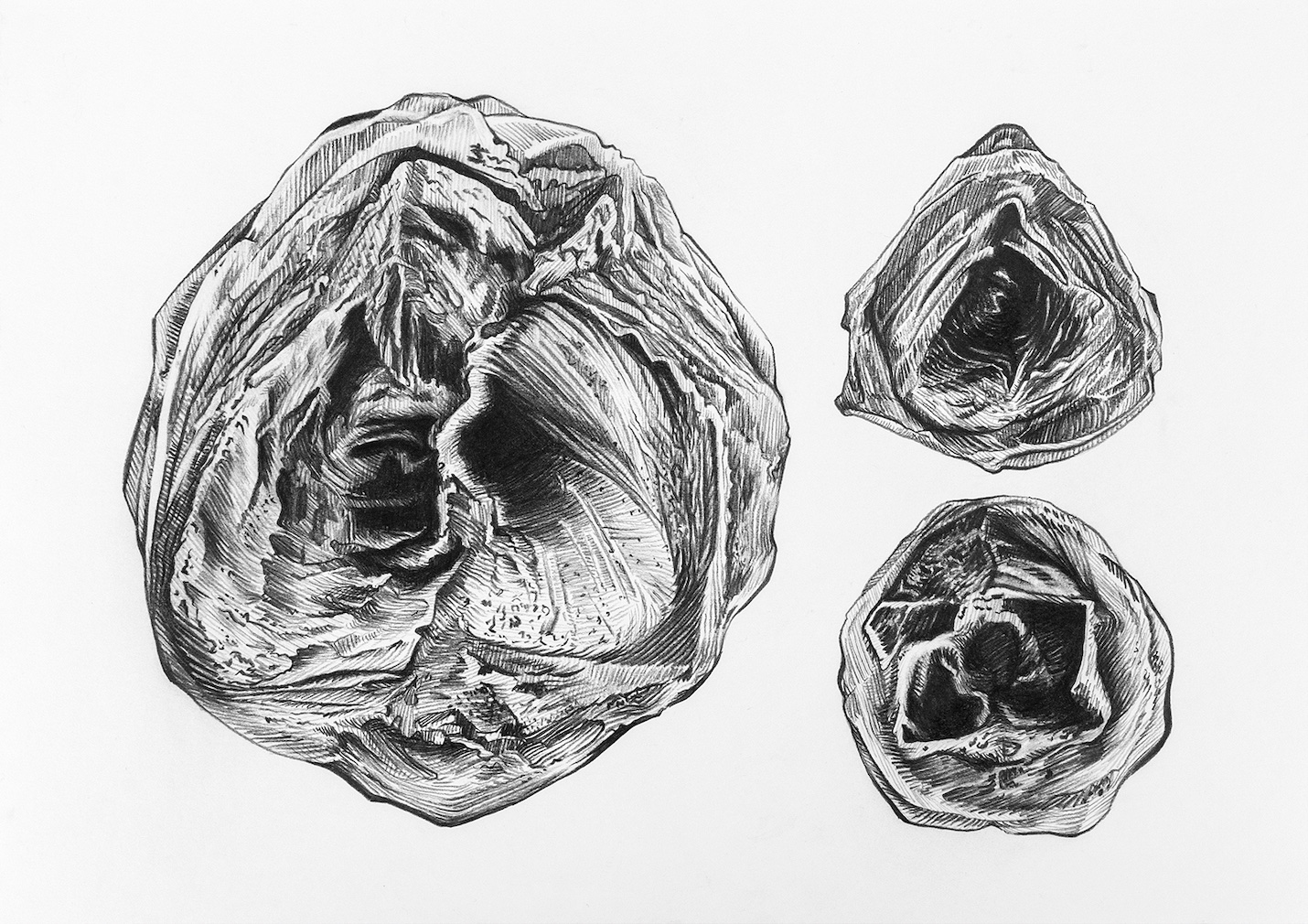

The exhibition consists of a series of pencil drawings on paper of the found meteorites, as well as certain scenes depicting the process of their discovery and transport. These drawings appear to be taken from a fictional geology encyclopedia. Observing the images, I feel that the artist uses drawing as a tool to think materially. Each material makes the history that produces and accompanies it evident. Carbon as an element is presented both in the graphite used for drawing lines and in the meteorites recorded on paper. Sometimes, I believe that each person has a special sensitivity to certain materials, and these affinities are the result of billions of years in the material history of the universe. Accompanying the drawings are replicas of the exhibited meteorites. Precious and mysterious pieces in a museum of fictional objects that, through their shapes, textures, and colors, evoke an almost seductive sympathy. Descriptive cards divided into the following categories accompany them: history, physical characteristics, petrography, geochemistry, classification.

From a stone, one can say when it was found, by whom, where, what color it is, how much it measures, that its chemical composition consists of 93% iron, 5.8% nickel, 0.42% cobalt, 0.46% phosphorus, and 0.28% sulfur, if it has texture, if it reflects light, what its scientific name is, what its whereabouts were, among many other details. But what can be said of a fictitious stone or an impossible stone? Perhaps exactly the same thing can be said.

I particularly like this piece because it shows two positions that although they seem antagonistic, are actually not. On the one hand, like any scientific document, it begins with a descriptive exercise: interpretation appears as a way to direct the materiality of any object, and this activity is mediated by factors that produce knowledge as a form of narration. On the other hand, it shows how the agency of materials shakes and overflows all limits of representation, allowing objects to enter into different relationships, with many of them being imaginary. In the exhibition, it is not known what is reality and what is fiction, but that ceases to matter when observing the unfolding that objects are capable of as they inhabit that tension. The artist also presents a logbook of notes on fallen objects and a display of space debris, which announces the omnipresence of plastic inscribed in rocks and scattered on the ground, water, and air, under our skin, and even around the orbit of our planet. This is a particular feature of the material history of our time.

Paleontología Sideral unfolds a speculative methodology in which the artist uses the visual narrative of science and the natural history museum to show that knowledge of objects within that belief system stems from an exercise of imagination, allowing the exhibition to become a safe place for objects to rest from their claim to truth, by showing that material speculation is what sustains the links between narratives and visualities. But at the same time, it subtly reveals that what underlies that narrative is encrypted in moral and policing aspirations that natural history museums support. This construction of the world responds to an exercise of legitimation in the quest to hoard truth for human plunder and profit, also revealing the colonial origin of the categories and methods with which the natural world has been analyzed and described. The consequences of these systematic classifications of knowledge are devices of perception that have involved an imposition and a cultural and political domination over materiality and, even more, over the possible and impossible imaginaries of the natural. It is in the awareness of this capture that the creation of speculative knowledge of objects is proposed to open the flow of material imagination.

Meteorites are a paradigmatic case of wonder, as each stone harbors the great mystery of matter, the mystery that introduces us to the deep time of that which traverses the living and goes beyond it. I wonder, in the face of the ecological catastrophe we witness today, if we can relate to existence and ruin without the notion of life and organicity as moralizing mediation.

Stones hold the memory of the forces that shaped the universe. Between the earth's core and the creation of the first galaxies, the deep time of the inert pulsates simultaneously. The crater contains the latent vibration of the imprint of a collision as the origin of the possible and the impossible. We live in uncertain times and a crisis of expectations; old worlds are changing out of sync, and new worlds are plunging into confusion. What questions will we now address to the objects? How will we be able to intuit something in them without the desire to precede an answer? A world can be everything that exists even if we do not obtain answers, but perhaps we can trust in that which is not contained in presence, look at the sky with different eyes, ask it new questions, rearrange the data in another way, always leave suspicion open as the first step toward the possible.

Translated to English by Sebastián Antón-Ojeda

Published on November 19 2023