Review

On Yellow Transitions: About 'Dos Incisivos' by Ulrik López Medel at the Anahuacalli

by Jimena Cervantes

Reading time

7 min

To articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize

it "the way it really was."

It means to seize hold of a memory

as it flashes up at a moment of danger.

— Walter Benjamin, Theses on the Philosophy of History

The Anahuacalli now exhibits Dos Incisivos by Mexican artist Ulrik López Medel. The show consists of 24 pieces created between 2022 and 2024, mostly made with materials such as paper, adobe, and galvanized sheet metal. The exhibition presents both the artist's own works and an intervention on the museum's collection objects.

On the ground floor, five pieces are displayed across three rooms. One piece caught my attention: Instalación con cajas, archivo bibliográfico y piezas de la colección MDRA [Installation with crates, bibliographic archive, and pieces from the MDRA collection]. It consists of a series of fluorescent orange plastic crates, some covered with wooden boards and others with transparent plastic under which certain objects and stones peek out. On top of the wooden lids are vessels and two cardboard boxes worn by time. Despite their deteriorated state, the boxes retain labels with the logos of the products they originally contained. Among them, one shows the logo of Ron Batey, a company from Córdoba, Veracruz, that disappeared from the market in the 1970s but, for 30 years, supplied the entire country and exported a rum formula from Jamaica.

On the one hand, it draws an interesting line through the multiple layers of meaning that cross the idea of exchange, as it shows that the history of objects must consider their relationship with the history of materials and goods. This connection reveals several dynamics that influence the transit of objects through different cultures, as well as the relationships of dependence that involve them in the complex world of the trade of imaginaries, with its economic and political negotiations, which are necessary to build any type of heritage project. On the other hand, the piece subtly suggests a moment before the categorization of objects: the time of transit between when something is extracted from its original context and its subsequent organization. This space of temporal 'indetermination' appears as a conceptual strategy throughout the exhibition.

The curatorial text notes that the artist 'claims the freedom to relate to culture without understanding it.'* This phrase makes me think about a series of issues when it comes to recovering the historical character of any cultural operation, about how our lack of knowledge regarding the ways these operations are carried out and the mediations that produce them have led us to a depoliticization in the ways we relate to each other. However, the freedom he speaks of is closely linked to the possibility of imagining new relationships, and that daring is already a political act.

In my view, it is advisable to approach a more or less serious understanding of the density of material transits in both time and space and their capacity to produce meaning in order to address the relationships between visual narratives of the past linked to the exercises of national identity construction and the role that the reinterpretation of cultural techniques plays in the search to generate 'new stories and new presents,' issues that the exhibition brings to light.

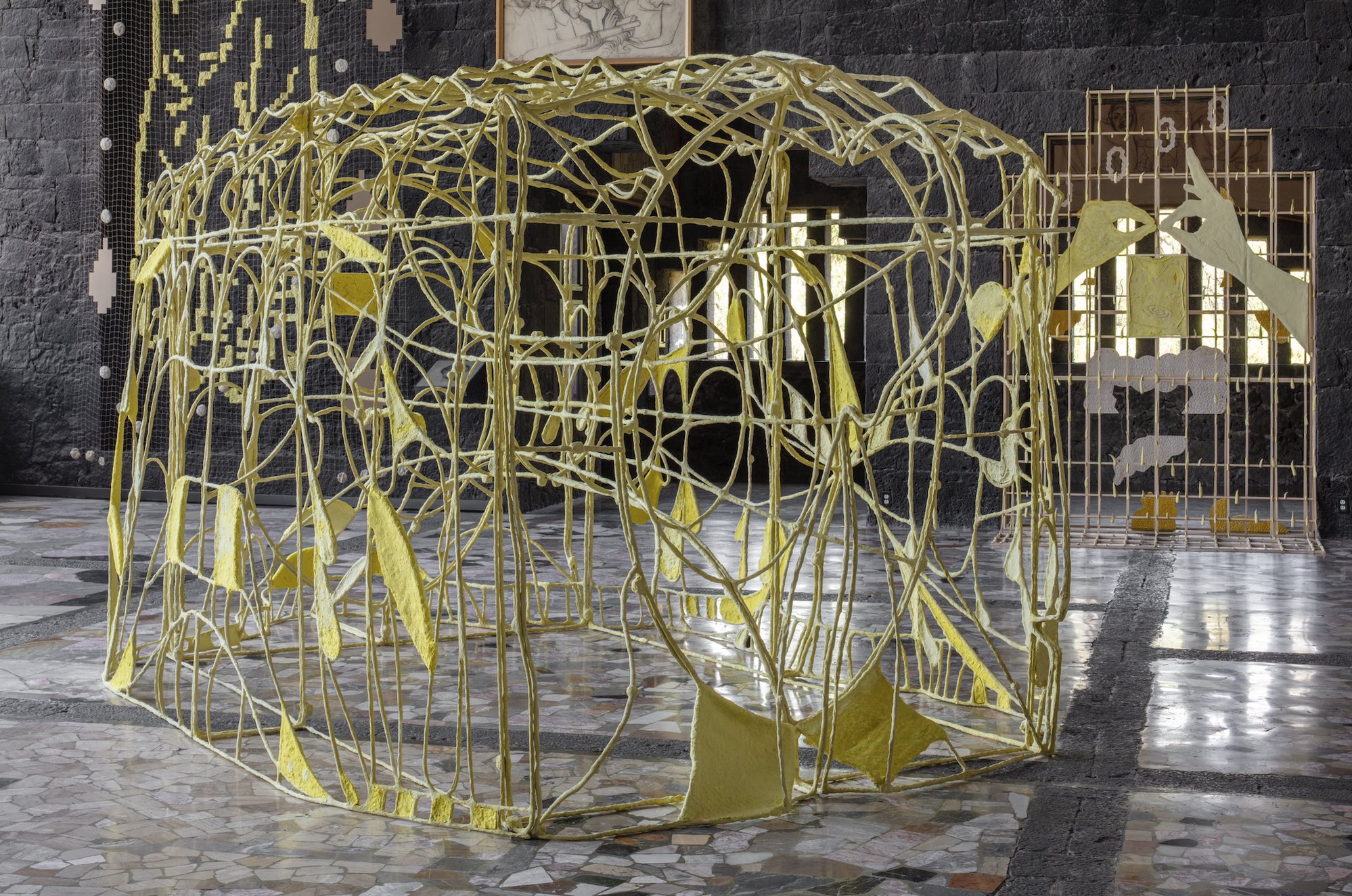

On the first floor, approximately 11 pieces are displayed in the central room of the museum. The first thing that catches the eye is a mysterious figure that seems to simulate a bird's nest, the sketch of a body's interior, a hut, a spiral journey into a deep dream, or a mirror that must be crossed. The piece is titled Jacal, a sculpture made of metal structures covered with papier-mâché.

In it, the artist once again creates an operation in which various layers of meaning of the materials are juxtaposed. Jacales are known as rustic dwellings typical of rural areas in Mexico, made with natural materials that appear antagonistic to the aspirations of modern life. The piece introduces a reading of this contradiction while allowing us to think of other possible relationships between the container and the contained as the original dimensions of home.

The idea of the contained is rescued from another place when the body appears fragmented and disseminated throughout the museum space. This is evident in pieces such as Pie floreciendo, Pie en el jardín o Espejo amarillo [Flowering Foot, Foot in the Garden, or Yellow Mirror]. Made of papier-mâché, they show different gestures of the body in poetic relationships with the space. It seems that by thinking of the jacal as a corporeal entity, located in the center of the museum's main hall, the sculpture stands pointing to a place, implying a redistribution of the social elements that are in that specific space, just as the parts of the fragmented body are distributed throughout the museum space.

This connects with another gesture of the pieces: most are yellow. The exhibition is inspired by Amacoztitlán, 'The Place of Yellow Paper,' a town that paid tribute to the Mexica. In her text El papel amate, sagrado, profano, proscrito [Amate Paper: Sacred, Profane, Forbidden,] Citlali López mentions that Tenochtitlan, being an urban settlement, concentrated a high percentage of non-agricultural population that necessarily depended on the market and tribute from the countryside and the agricultural towns under its control. For the Mexica, the subjected places could retain their local organization, their norms, their lands, and resources, as long as they fulfilled the delivery of assigned tributes.

Through tribute, a large quantity and variety of goods entered Tenochtitlan, manufactured objects besides food and all kinds of everyday and luxury items: cotton dresses, blankets, and huipiles, weapons, firewood, gourds, tecomates, copal, copper objects, precious stones, and amate paper. In this way, paper, as a tax extracted from the dominated peoples, was part of the mechanisms of state coercion. The history of pre-Hispanic paper changed drastically with the arrival of the Spanish, as in the primary interest of silver and gold plunder, paper lost its value as tribute, trade object, and sacred element.

This is interesting because it reconnects us with the relevance of material exchanges as a key to understanding the forms of identity mediated by relationships of dependence that accompany any material history of objects and their transits of value. The artist's work manages to show, through his reinterpretation of the papier-mâché technique, the awareness that a change in sensitive relations with objects implies a visibility of the material operations that mediate them.

Finally, on the second level, there are eight pieces, mostly made of metal and galvanized sheet metal. Unlike the previous works that referred to the dispersion of the contained, the pieces on the second level deal with the moment when the body, which previously appeared fragmented, is reunited under the sunlight as a new container. Pieces that dialogue with the idea of rest and sleep as moments that allow reopening the contained, but in the form of smoke that disperses in the night sky, only to return to the body the next morning.

To conclude my text, I would like to reflect on the curatorial proposal from the viewer's perspective. I believe there are a series of successes in the interaction between López Medel's works and the dialogues with the museum's collection, as it appears as a trigger to critically reexamine not the collection itself, but rather the discursive and material possibilities of the artist's explorations. However, at the museographic level, I find certain difficulties that visitors may encounter when seeking a language to reflect on their encounters with contemporary art. Can these types of exhibitions truly open alternative modes of participation for viewers beyond the normative and authorized understandings of cultural heritage (its architecture, collections, or landscape)? Or does their encounter only make the gap that separates the universes of references that articulate contemporary art practice from the spaces and issues they seek to reflect upon more evident?

* Fragment of the text written by Karla Niño de Rivera, curator of the exhibition

Published on August 14 2024