Interview

Land: An Interview with Kon Trubkovich

by Byron Davies & Julián Madero

At Morán Morán

Reading time

7 min

Since his debut in 2006, at MOMA’s PS1 in New York, Kon Trubkovich (born in Moscow in 1979) has developed a body of work that complicates relationships between painting, the electronic image, and memory, all via operations that are close to reappropriation, reuse, and found footage. Although the experience of his displacement from the USSR to the US at the age of eleven informs a large part of his work, confluences between the personal and the collective are what make his poetics especially taut, collapsing times and geographies as well as mediums and narratives.

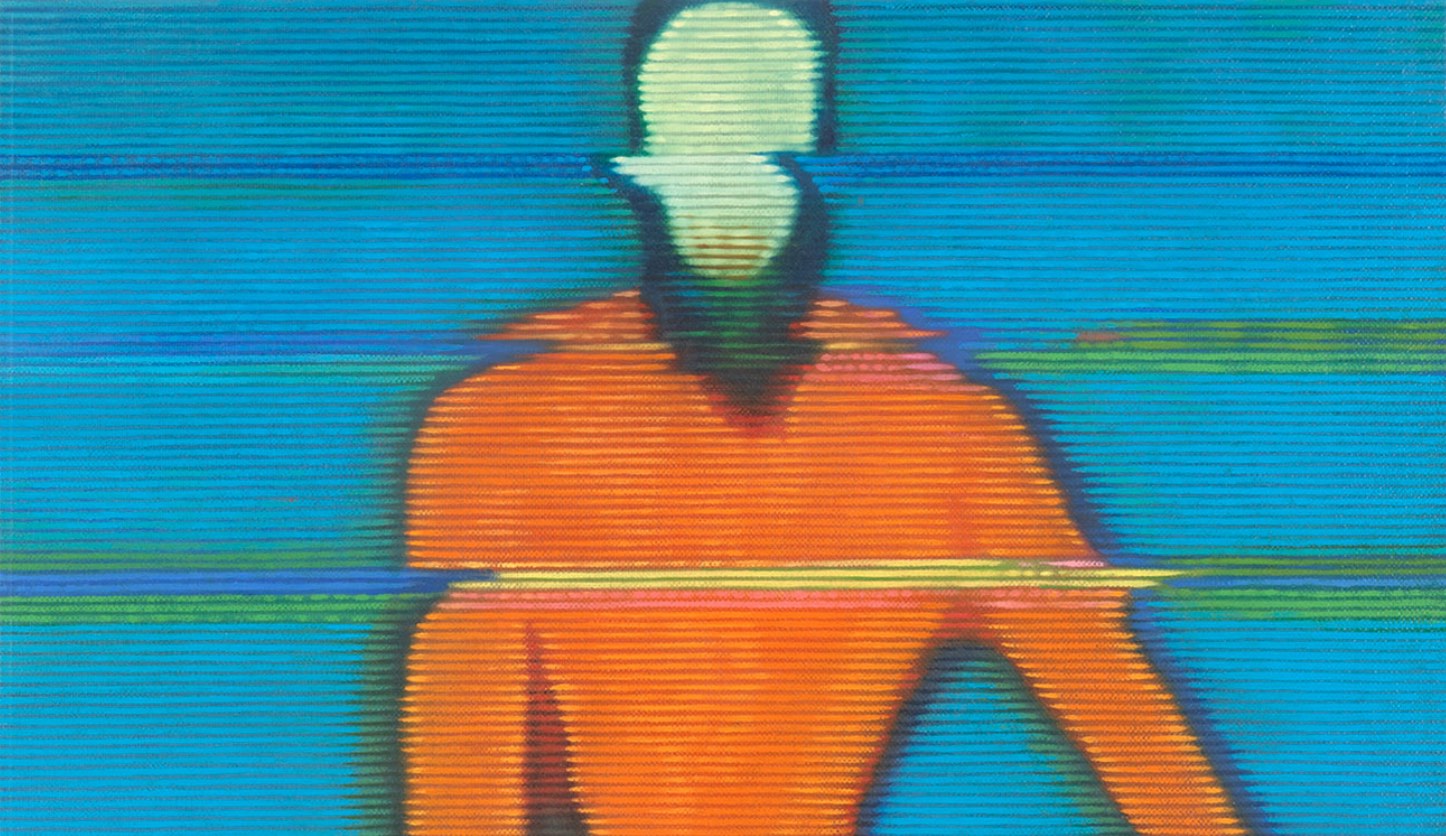

In the last several years, Trubkovich has constructed a particular stylistic operation—comparable to practices like circuit bending—that consists of processing visual material (whether reappropriated or produced by Trubkovich himself), using near-obsolescent VHS players, pausing the videos in order to extract frames, and thus making a substantial modification to the original source. This pre-pictorial operation generates the model that is then taken to the canvas, using a meticulous technique that emulates the scan lines of the illuminated screen.

On the occasion of his first exhibition in Mexico, at the gallery Morán Morán, we talked with Trubkovich about the interests, conundrums, and references running throughout the show.

Byron Davies. Your exhibition is called Land, and you’re in a new land. This is your first show in Mexico, and a lot of your work is concerned with your experiences of your early childhood in the Soviet Union and then moving to the U.S., as well as connections and disconnections arising from that experience. So what’s significant about coming to a new place for showing your work?

Kon Trubkovich. It’s not so much the significance of coming to a new place, but to speak to a more universal thing: of dislocation, of memory, and the way that memory of the past converges with the present. So this is a more universal experience that anyone in any land can relate to. In that sense, what I’ve been trying to do with my work over the past decade is to strip away the layers of the personal, and to reveal a little more of the universal or collective. I think that this show was kind of forced upon me, since I started working on it right when the war in Ukraine started. The title comes from that: all the different tragedies involved, the moral catastrophe. But then I sought to distill that into something: the word “land” became the governing principle of all this. The work speaks to a kind of collective memory: the sense of remembering or forgetting that I think anyone can relate to.

Julián Madero. Why did you decide to turn to Malevich for this series?

KT. When it comes specifically to Malevich, I had been preoccupied for years by his late period work, which comes after the pure abstraction (black square, white on white), the kind of radical suprematist style that he’s known for. There’s a period when he moves to Kyiv from St. Petersburg, and he’s teaching at the university, and he starts to paint in a hybrid style, but figurative. And I always thought about this, since if you read his biography, he comes from a Polish family, his father is a manager in a sugar factory in western Ukraine. You have to understand: those borders, that land, was always shifting. It was Poland, Lithuania, Prussia, Ukraine. The constant wars that happened in that area shifted those borders, it was completely fluid. So he grows up in this borderless land, surrounded by a kind of rural peasant village people. I’ve always thought that those painting were memories of that time, of his childhood. That was my initial connection to this work, since I always think of my own work through this prism of childhood memory and of course the layer of mediation—the television screen—is a metaphor for that. That’s why these Malevich works always kind of appealed to me.

I have to say that this show is bracketed by this war. I started working when the war started. It was impossible for me to keep that out of my psyche. But I couldn’t paint the images I saw in television: they were too gruesome; I couldn’t bring myself to do it. So I started thinking of Ukrainians, evacuees, the mass movement of people, and I started thinking of them as Malevich paintings. That’s why I painted these paintings, though I changed them. They’re not honest reproductions of Malevich paintings. They’re changed: the colors, the compositions, they’re re-cropped. So I’m pulling some of my visual cues from what I’m seeing on television.

BD. What then do you see as the differences between the electronic image and the painting image, and how does your work complicate that?

KT. It’s interesting, because it’s not that I see any differences in them. The way I paint is to break those things apart, kind of molecularly, and to try to understand them. Initially my task was to recreate this video image. The more I work and the more my scope as a painter expands, the more I try to balance that mechanical image with the painting space, where the painting has a kind of spatial aspect to it. So I don’t know if I’m answering your question directly, because I don’t know if I see a difference. When you begin to paint, the logic of the canvas really does take over. If you stop and think, “I’m going to make this painting that’s going to look like a JPEG,” I think you’re going to end up with something that looks like a JPEG. I’m really trying to create paintings. I think way beyond that. I think about them as objects in space, and how they operate in that space. With this show you’ll see quite a lot more gestural interventions into the paintings. Like with the fight painting called Capsize [part of the Golden Ratio series], there are large gestural parts that are kind of an antidote to the mechanical thing. All of this is sometimes in conflict, sometimes in concert, but they have a kind of relationship on the surface, and that’s more important for me than reproducing a digital feeling.

JM. Elsewhere you’ve talked about having a plan or a routine, of going to your studio and working, in contrast to what happens when you wait for inspiration. How does this tension currently operate in your work?

KT. I don’t see those things as contradictory. The routine is just showing up. I come to the studio—that’s my routine. But the studio is the improvisational space. But the routine is to arrive there every day. And if nothing happens, nothing happens. And if something happens, something happens. And there are different stages in my work, where some of it is very much rooted in labor, very labor-intensive. But then some of it isn’t, some of can be a matter of moving around, very fluid, figuring out the space of the painting, and that is very improvisational, very intuitive. And then the painting begins to crystallize, and I see how it’s going to work spatially, and I have to fill out some details, and it becomes quite laborious.

BD. I wonder if there’s something about your attraction to the audiovisual in connection with questions of return.

KT. I think it’s just the effect of seeing these things on television, that being the mediating texture of memory. To me, that video image is truer as an interpretation of memory than a photographic image, because to me memory is flawed and decaying.

BD. We often have different mythologies or vocabularies for talking about the electronic image as opposed to painting. For example, we might think that a painting is its own world.

KT. I truly believe that. This is where I live: I live in the painting as its own world, rather than in digital or analog or whatever.

Published on July 14 2022