Interview

The Everyday Absurd: Gabriel Rico at OMR

by Fabiola Talavera

“I May Use An Electric Drill, But I Also Use A Hammer”

Reading time

6 min

Gabriel Rico presents his exhibition I May Use An Electric Drill, But I Also Use A Hammer at Mexico City’s OMR gallery.*1 I had the opportunity to talk with the artist about his work process, the products of globalization, new digital paradigms, and his other reflections on the contemporary world.

As one enters the exhibition, a strange static noise invades the main room. At first glance, one is confronted by a stuffed oryx and deer, staring at each other. Embedded in their horns are plastic balls in bright colors and of different sizes. Surrounding this particular scene are a few rocks. The walls are covered entirely by pieces of branches; on one of the walls, the arrangement is interrupted by a circle, a square, and a triangle in gold metal and blue neon light.

The selection of materials making up the installation involves a long process in which Gabriel places particular emphasis on the textures of objects. The audio comes from a collaboration between Rico and the New York music label Blank Forms, in which an analog recording was digitized, thus maintaining the effects provided to the sound by dirt and static. Among the stones, there are basalts, quarries, and granites that the artist collected on different trips. There are plastic sports balls in shrill oranges and yellows. It’s difficult to draw any line between natural and artificial elements; of the animals in the scene, all we see are their taxidermal remains.

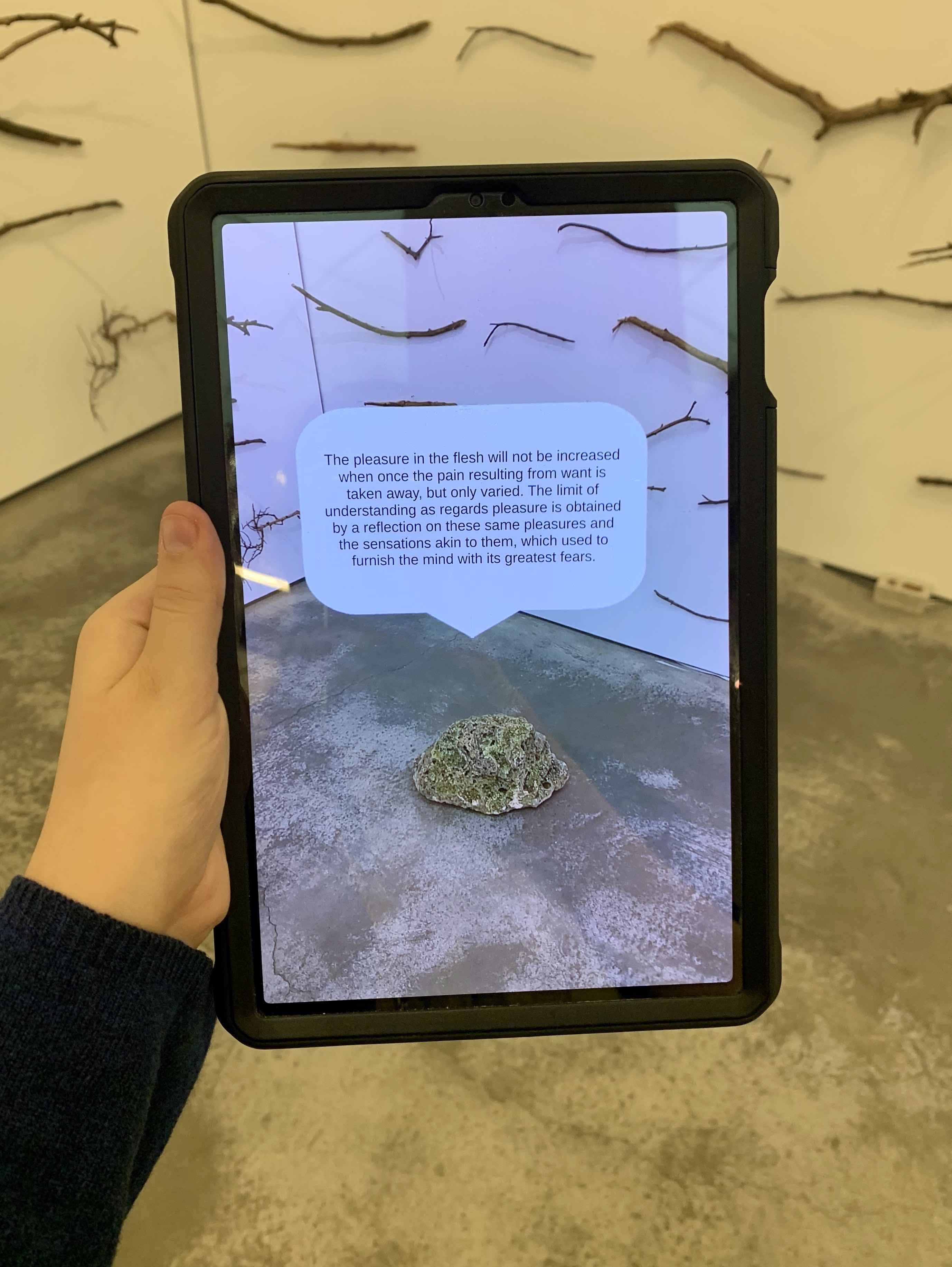

Further on, some electronic tablets invite visitors to go back through the exhibition, this time via a screen. As they rise into view, a new animated world appears: a digital fox prowls the scene, stuffed animals incarnate a conversation about machines and living organisms, and in which they imagine a satellite and planet earth. The stones recite phrases from Epicurus about living a pleasant life, and they reflect on everyday objects like cokes, tennis rackets, hammers, and other irreverent human inventions.

Ideas of the absurd and the antithetical were fundamental in selecting the digital animations and physical elements. They opened up the possibility of conspiring along the lines of anthropomorphizing ordinary objects and challenging the laws of physics. We observe, for example, the perimeters of the platonic geometries on the wall, illuminated using digital flames—an approach that imagines the existence of luminous stars with shapes other than what the laws of physics allow. In their atomic counterpart, Gabriel points out to me the similarity between the hexagons of soccer balls and carbon molecules, the main ingredient of all that’s alive.

Unlike other augmented reality applications that play in constant short loops, the entire duration of this experience—allowing one to see and read all its contents—is close to an hour. Certain decisions, such as placing branches on all the walls, correspond to the technical needs of the tablets’ cameras, so that they can measure the dimensions of their location in space, and also situate ourselves outside the usual white cube of galleries. The technological development necessary for the show took Rico and his team of programmers more than two years.

Rico’s work constantly refers to the translation of languages between disciplines. The conversation between the oryx and the deer quotes excerpts from the book Epistemic Cultures: How the Sciences Make Knowledge (Harvard University Press, 1999) by the sociologist Karin Knorr Cetina, which presents an argument about how molecular biology and high-energy physics produce knowledge under the codes of each of these scientific fields. Similarly, the exhibition’s title, I may use a an electric drill but I also use a hammer, refers to the possibility of analyzing and carrying out a solution to a problem in multiple ways.

Gabriel Rico considers himself a research medium, based on his own human experience. On many occasions, the objects that Gabriel selects to be represented in his pieces are products of globalization, commodities that likewise carry negative connotations and that bear recognizable symbols across regional cultures.

In an observation regarding our pandemic times, Gabriel points out how the use of the internet and digital technologies have developed precipitously during the pandemic, which has forced many to be glued to the monitor so that they can continue their everyday tasks: “Nothing more is needed for there to be operation rooms where there would no longer be humans and where we would inevitably become objects,” Rico remarks. Faced with this likely alienated future, he tells me about his special interest in making augmented reality a collective event that would distance itself from the usually solemn art gallery tours:

It seemed absurd to me that you had to wear goggles and abstract yourself from the physical world […] What I wanted was for this to be a shared experience and not a private one, that you could go with someone else with whom you could share a tablet and talk about what you both saw.

Usually focusing on sculpture and installation, this is Rico’s first time working with digital media. His objective is to enhance the experience of the senses and the possible meanings of the elements—all while integrating them into this exhibition. At the same time, experiencing the meditation of the screen is not necessary for enjoying the exhibition:

I was very interested in the fact that you didn’t have to be an expert in contemporary art in order to enjoy the exhibition, and that if you were an expert in contemporary art, literature, philosophy, or applied science, it would be deep enough to allow for this kind of dialogue.

To appreciate Gabriel’s work it’s not necessary to know more, but rather to know less: to appreciate the shapes and textures that these very objects have, to ask ourselves about the ways in which we come to agree on their meaning, the implications added by the context in which they’re situated and the ways in which we relate to each other through them. Day by day, a series of signs and images appear in front of us. Unconsciously, our mind decodes and interprets them. We can continue in this automatic march, but we can also recognize and question the epistemic structures that have made us believe that our world is merely mundane.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

*1: In September 2021, Rico will open the first exhibition of the Institute of Contemporary Art San Diego, a binational museum whose mission is to "question everything".

Published on Apr 8 2021