Review

Guess Who. On "Broken Column" at the Museo de la Ciudad de México

by Constanza Dozal

Reading time

6 min

In Mexico City we love to play guess who: who is in the latest exhibition, who knows where that bar is, who knows the aunt of the friend of the collector’s brother who can lend you an artwork, who fixed the museum’s infamous air-conditioning system.

The exhibition Columna Rota [Broken Column,] on view at the Museo de la Ciudad de México through March 1st, 2026, takes this game to its extreme. The curator-organizer, Francisco Berzunza, invited his friends to create, finance, and present the show, which required a considerable investment for the production of commissioned works and the renovation of multiple galleries.

The air-conditioning system is mentioned in the booklet that accompanies the exhibition, alongside other scandalous personal confessions, comments on the works, and tributes to friends who are no longer alive. The publication explains the affective network that sustains the exhibition; I feel a strange combination of suspicion and admiration as I read it. If the intimacy of life is so tightly interwoven into the project, I wonder how one can comment on it without what is said turning into a personal attack. How could one point out the mistakes of someone who remembers friends who died by suicide and, a few pages later, confesses to having attempted it themselves?

I also wonder why there is such insistence on the monetary value of the works, the payments they required, and the management difficulties involved in producing the exhibition—unfortunately similar to the challenges faced daily by public museum teams.

Columna Rota takes its name from Frida Kahlo’s¹ work of the same title and presents itself as a thematic exploration of rejection. It brings together works by more than fifty artists, texts by more than twenty creators, and the collective effort of hundreds of people; part of the organizing team is acknowledged in the credits.

We might marvel at the tenderness and commitment involved in helping a friend, or we might ask whether it is necessary to have investor friends in order to carry out a project. We might even ask how many market interests surround it. But we might also ask what the exhibition proposes beyond the anecdotes that orbit it.

Perhaps the work that offers the most clues is ¿A dónde va la luz cuando se apaga? [Where Does the Light Go When It Goes Out?] by the collective Lagartijas Tiradas al Sol. The installation presents a wooden set with plastic plants, simulating a room with colored walls, onto which a video is projected or where an actor appears during scheduled activations.

In the piece, a male voice-over alternates with men and women who responded to a casting call: we watch them in acting tests, hear them talk about experiences and explain their motivations for auditioning. The voice explains that among all types of artists, the rejection actresses endure is the hardest to overcome: when one rejects an actress, one is not rejecting her artwork, but the person herself—her appearance, her way of being.

Because of how the video is constructed, it seems as though the actresses are speaking directly to you. We are the ones who would reject or accept them. But, as in other works by the collective, the boundary between fiction and reality is ambiguous. It is unclear whether the casting was staged, whether the testimonies are scripted, or whether the text is an exercise in dramaturgy. The installation shows us enough of its staging to make us doubt it.

Doubt implies a shift in perspective, a step backward to examine how something is constructed. The space created by this displacement enables many forms of critique and transforms our experience. However, one must know the narrative codes of that “something” in order to find where it fractures.

Other works in Columna Rota perform a similar operation to that of Lagartijas, but their references could be illuminated more clearly. What could be a formidable exhibition of institutional critique instead turns inward and darkens.

Some works are placed in whimsical locations that generate surprise, such as Nahum B. Zenil’s painting above a doorframe or Shilpa Gupta’s tiny installation—barely six centimeters—floating on a small wall. Other placements eclipse the works, as with El Gran Cometa de 1882 [The Great Comet of 1882] by José María Velasco: hung so high that anyone under 1.60 meters tall cannot see it, let alone a child or a wheelchair user—like Frida.

Despite some missteps, the experience of visiting the exhibition is enjoyable. In Mexico, it is uncommon to use artworks to divide galleries and set the rhythm of the visit. The installation adopts this strategy and takes advantage of both the large rooms and the triple-height ceilings of its viceregal building to create small ecosystems. Rather than assigning each work a closed space, it allows them to intertwine.

Something particular happened to me with Swarm by Zein Majali. The piece is an animated video in which we follow a truck—strangely similar to a pesero minibus—along a border landscape, sometimes desert-like, sometimes urban. The scenery could be mistaken for Mexico’s northern border, were it not for the brief appearance of signs with Arabic characters. Unable to recognize the setting as the border between Jordan and Palestine, I only realized that it spoke of both boundaries once I got home and researched the work.

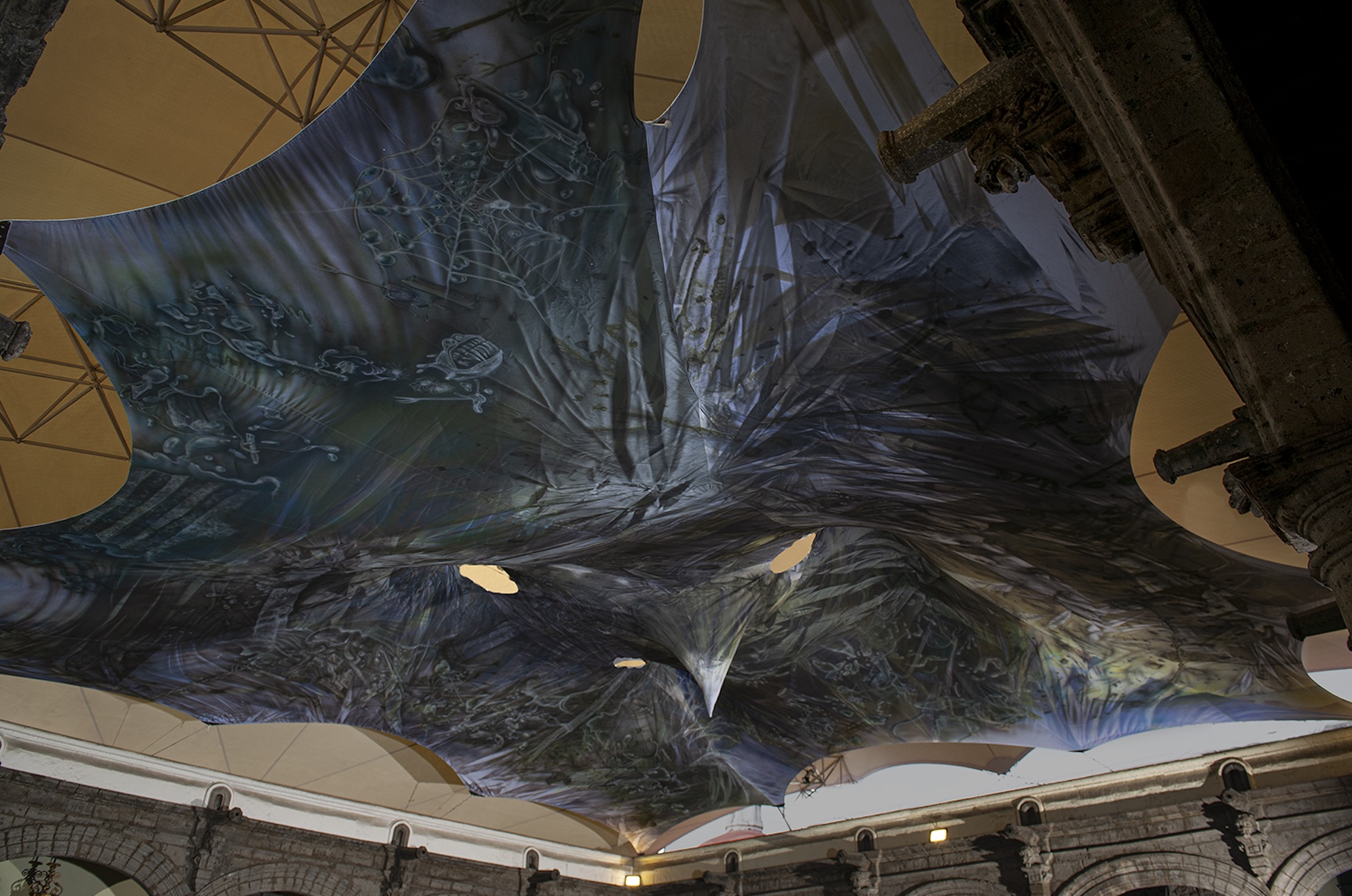

Some pieces are easier to approach, such as La blanda patria [The Soft Homeland,] a spectacular monumental installation by José Eduardo Barajas that covers the museum’s central courtyard. We find spiderwebs with dewdrops, watery landscapes, and what appears to be a rib cage. These could reference the artist’s personal experiences, reflect on his own trajectory,² comment on muralism and the city’s hydrological history, or—within a state-run venue—serve as a reminder of the thousands of bodies buried in the national territory.

Do we want to take pride in the city’s resilience, or discover that we are standing inside a mass grave? Dance to the music of Swarm, or recall the similarities between Palestinian territory and the one we inhabit? Take the words of a rejected actor as a personal story, or as an allegory of the collective?

There are small anomalies and fractures in the exhibition’s works that displace its apparent egomania toward a shared experience, but rather than establishing an open conversation, the exhibition whispers and murmurs. We are left only to guess why this is so.

Translated into English by Luis Sokol

Cover picture: José Eduardo Barajas, "La blanda patria", in the exhibition "Broken Column", Museo de la CIudad de México. Photo: Tom de Peyret

1: Even though Frida Kahlo is possibly the most renowned artist who had mobility problems, one can only find somewhere to sit in one of the almost ten rooms of the exhibition "Columna Rota".

2: I think about the exhibition he presented at Proyectos Multipropósito in 2023, where he covered the ceiling of an old call center with a grid of paintings.

Published on Jan 31 2026