Víctor Sulser

Analytics of the Birds for a Nonexistent Cantina

El Castillo de Chapultepec presents Analytics of the Birds for a Nonexistent Cantina by Víctor Sulser. Curated by Roselin Rodríguez Espinosa.

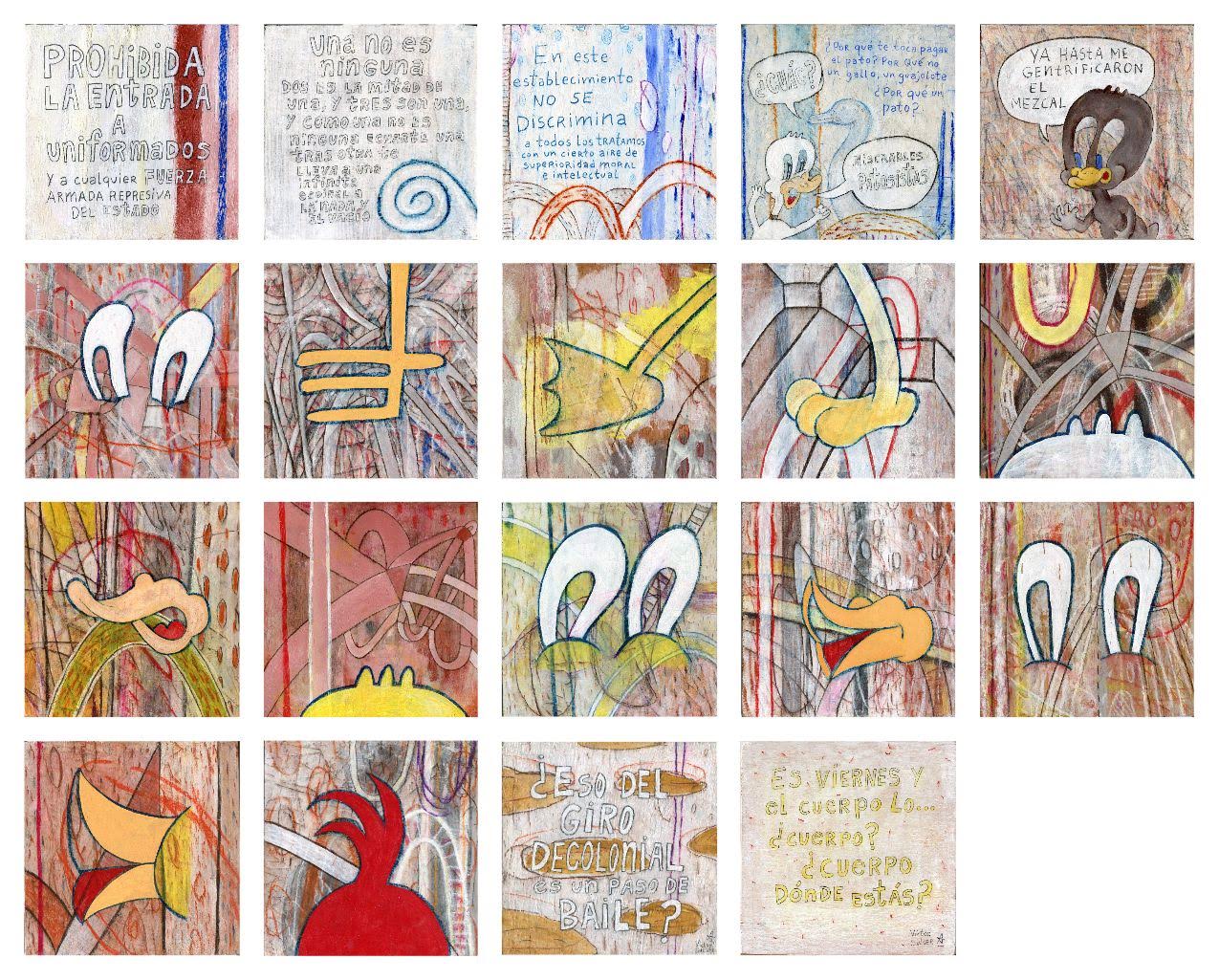

We might remember that when a bird appears in a cartoon in a situation of alarm, crisis, foreboding of an accident, or extreme emotion, what we see—suddenly—is a part of its body: a leg or a close-up of a tuft of feathers, a beak suspended in the air, or eyes about to burst. Suddenly the bird dissects itself to warn us that something has gone out of control and is about to collapse. For our peace of mind, the episode doesn't end there, the bird always reassembles and the plot continues.

This is the type of unexpected conversation we can have with Víctor Sulser when we ask him what he's been thinking about lately and what series of his distinctive "paintings on little wooden boards" he would like to create. This is how this Analytics of the Birds emerged, which is a meticulous exercise in observing how our dramatic subjectivity is visually constructed through the consumption of cartoons. Close attention to the sequence of collapse whose separate gestures are fragments so absurd that they unleash bewildered laughter with questions: how can any given situation–literally–fall apart so much? How does a chain of improbable events end up happening? Another conversation that emerged with Sulser was his vague memory of having been in the same place where the lobby of El Castillo de Chapultepec now stands, one night in an imprecise situation that mixed the atmosphere of a cantina, cabaret, and performance show.

The intersection between art and entertainment spaces has a long history in Mexico. It suffices to remember two moments: When Diego Rivera wrote an article celebrating mural painting in pulquerías bringing attention to this practice and, more recently, when the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) opened a museum where the cantina El Nivel previously existed, famous among the artistic community of the Distrito Federal and a temple for many during their formative years at the Academia de San Carlos. The latter fact, which Sulser qualifies as criminal, extinguished a cultural space that was key for his generation. For the artist, the memory of those now-extinct cantinas haunts the spaces of contemporary art, increasingly immersed in urban gentrification processes that have eliminated those places and with them an entire way of socializing.

It is in that drift that some of the vignettes show reassembled ducks that utter typically cantina-like phrases, evoking that memory of extinct places, of which their language persists. Another part of the selection of paintings gathers some of the well-known art memes that the artist created during the Covid lockdown and that circulated only on social media at the time. These in particular combine the presumed seriousness of fashionable topics in academic art markets such as the decolonial turn or the place of the body with the incredulous crudeness of everyday speech, where art can sometimes be anything, even a dance step.

The materiality of the artworks also refers to other extra-artistic realms that have nourished the production of conceptualisms since the 1970s in Mexico: stationery stores or papelerías. The artworks have as support recycled wooden boards of the standard 20 x 20 cm size acquired in these shops, and which are commonly used by children to make school dioramas. On them Víctor paints with acrylic, oil, pastel, graphite, combining material conventions of art with objects valued as crafts.

Thus, the lobby reminds us that it is also a painting salon where the ducks explode upon sensing the disappearance of their favorite cantina and where a museum falls apart and reassembles while a conversation takes place at its counter.

–El Castillo de Chapultepec