Ernesto Briel

From Aion to Cronos: the art of Ernesto Briel

Exhibition

-> Sep 12 2024 – Oct 26 2024

Proyectos Monclova presents De Aion a Cronos: el arte de Ernesto Briel, a tribute to the Cuban artist.

If anything characterizes the work of Ernesto Briel, it is the way in which he works with the surface as the minimum space of painting, to pull out or uproot its formal powers. In this essay I propose an approach to his body of work as a whole—as a universe or a constellation—in which the bodies (artworks) that form it produce a field of forces and an interplay of tensions that simultaneously unfold in multiple directions and planes of affect and signification. Here I am not attempting to do a genealogy of his work, and less still a formal-historical review of it. Instead, I propose that this essay be read from an almost curatorial perspective, understanding that to arrange an artist’s work in space is to temporalize the works, to space them out. I use “spacing” as a verb here in the same way that Artaud conceived the scene: not as a place of action or of acting a plot, but as the temporalization of space, as spacing.

After reading the texts that discuss his work, or more to the point, the research papers and essays in the book Ernesto Briel: The Rest Is Silence, and after spending a good amount of time contemplating and analyzing—perhaps it would be better to say deciphering—his works, I decided to approach the work of this Cuban artist via the framework of relations and significations produced by a complex aesthetic system, that is, a poetics that does not evolve in a linear direction but rather deepens its powers of expression and signification; and further, in which this deepening would be inexplicable without the vital pathos that drives it: that which goes from the enthusiasm of an artist convinced of form as a utopia to one who pours it into the thickness and quietude of matter (color and texture) in the indeterminacy, anguish, and terror in the face of death.

In general, the critics and scholars of the works of this Cuban painter propose three phases in the development of his production: the first developing in Cuba where the artist signifies a sort of historical continuity between geometrical abstraction on the one hand and kinetic and Op Art on the art; the second marked by his migration to the United States, in which kineticism came to have an international scope; and the third, of a more existential disposition, which has to do with the outbreak of the HIV epidemic and Briel’s death from AIDS in 1993. To be sure, there is more than enough in these biographical chapters to explain Briel’s work. Nevertheless, I think that if in retrospect we read in his work a constellational cipher, we can see that it sets in motion a sort of aesthetic journey from Aion to Chronos. Aion is time as infinite: circular, without content, turning about itself; it signifies possibility and emptiness at the same time. Chronos is material time, the time of life, that which devours life.

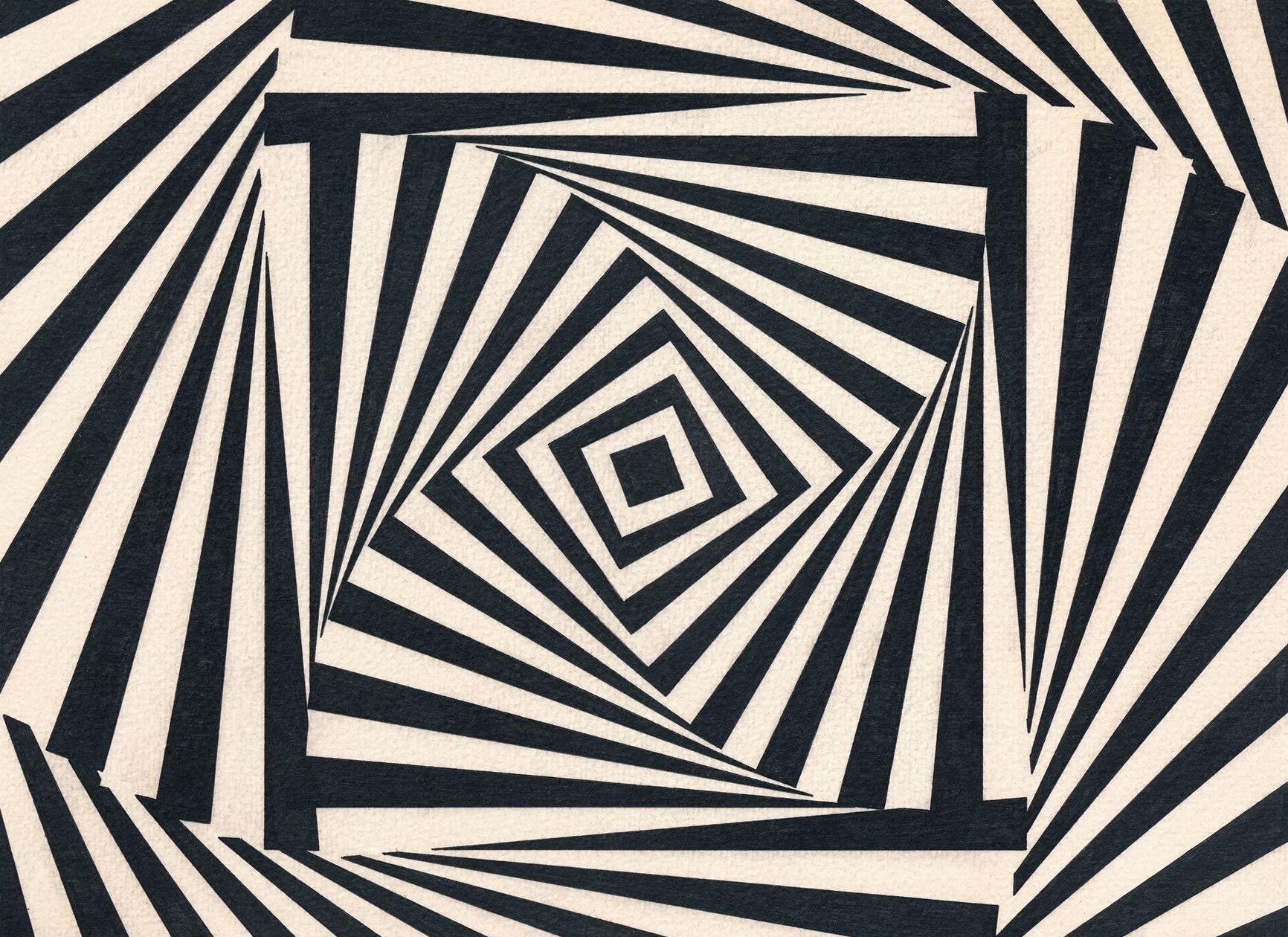

It is doubtless and obvious that much of Ernesto Briel’s production involves a tension between geometrical abstraction on the one hand, and Op Art and kineticism on the other. What matters here is to emphasize the internal tension among these aesthetic poetics, apart from the continuity that can be recognized between them in his corpus. Here it is important to highlight, problematize, or ask ourselves what this tension puts in play. Geometric abstraction is more stable than the forms that it produces, but above all it posits a certain universality of its forms, which are much nearer to the function that the concept has in thought; for its part, kineticism consists of illusions of form in becoming.

Beyond, or rather cutting across, discussions of context (political, social, artistic) that come into play in either of these poetics, what seems suggestive to me is to ask ourselves, aesthetically and ontologically, what in Ernesto Briel’s work creates the tension between geometrical abstraction and perceptual illusion.

One thing that the work from the 1970s has in common with that produced in the ’80s is not just the use of black and white as formal and perceptual minimums of production of the visible on the surface, but also an unfolding of forms as difference and repetition, these being produced as structuring in geometrical abstraction or as structured in kineticism. In other words, when I referred to the tension produced between abstraction and kineticism in Briel’s work as difference and repetition, I meant that the relation between form and surface in his work can be read as a production of intensive fields and not merely as the objective container of forms.

Certainly, having put this tension in the context of the 1970s and ’80s, these early works of Briel’s (from the 1960s and ’70s) can be valued and signified from the perspective of the political and aesthetic discussions proper to the Cold War. Nevertheless, beneath this whole discussion or historiographic-formal analysis, I find something deeper in the tension between geometric abstraction and kineticism with respect to a certain ontological consideration in his work.

As Antonio Eligio has observed, there is no doubt that in this deeper substrate of Briel’s geometricism, there function traces or marks in which abstract forms indicate a sacred order, archetypical of the cosmos. Forms are indices of immanent forces that cut across history; they are Pathosformeln, as Warburg proposes, through which Briel puts into operation the relationship between art, cosmos, and history. This is perhaps one of the elements most suggestive of the Cuban artist’s will to form. Although his drawing technique, use of line, black and white, and repetition as minimum elements of his aesthetic are hitched to the index of historicity of the industrial machinic imaginary of geometrical abstraction such as the avant-garde conceived it, they nevertheless surpass it toward a certain archetypal functioning of abstract forms, in the Jungian sense of the term. Whether or not one can affirm that this has the character of a metaphysical truth in Briel’s work aside, what matters here is to underscore the pretension to universality that can be read from the geometrical/kinetic abstraction in his work, that is, the scope of signification and meaning that abstraction can have as a fundamental resource in his work.

That assertion might seem like an exaggeration on my part. Nevertheless, as I proposed at the beginning of this brief essay, if we understand the relationship between geometrical abstraction and kineticism as a tension that spans the entirety of Ernesto Briel’s artistic production, that is, as the creative drive or a latency that lives at all times in his work, perhaps what I am talking about is a much richer and more complex poetics of painting than the mere appropriation and resignification of abstractionist traditions from the history of art. To make this argument, it suffices to notice how geometricism and kineticism drift in his later work. While it is certain that in the painting he produced in the late 1960s and above all in the ensuing decades, repetition, abstraction, and movement continue to be present, perhaps in an excessively aestheticizing way, it is also certain that in the paintings from the 1980s and ’90s there are two elements that twist—or perhaps better put, disturb—the tension between abstraction and kineticism: namely, assemblage and color.

These works are disturbing in two senses: first, as (de)compositional elements that interrupt the continuity, rhythm, harmony, and aesthetic solipsism proper to his earlier works; and secondly, this twisting of the structured/structuring tension that defines the constant feature from his earlier works to this time produces a hiatus and introduces a principle of chaos into his painting.

The assemblages or diptychs, or the illusion thereof, are hiatuses that function as caesuras: by separating, they unite, and by uniting, they separate—but what? A sort of abyss of the possible infinite, a mise-en-abyme of abstract forms in which line serves as a vortex of forms. Something similar but more radical happens with the use of color. Unlike the paintings from the 1970s, in which color functions on the same plane as geometrical forms and the repetition of figures, in the works from the late 1980s and ’90s, color is disruptive on the surface. In these works, color invades the forms and repetitions from below, to the point that it displaces or erases them. In these works, color is a sort of material thickness that buries forms in indeterminacy. These are not emotive abstractions, but rather a certain awareness of the indeterminate, of an ontological density that devours forms and movement, just as Chronos devours life.

There is one painting that seems to me to materialize this dialectic between emptiness and thickness as an erasure of forms and advent of the void: an untitled oil on canvas from 1989 that folds over all the elements and motifs that Briel could have drawn and painted in his works: where figuration is folded, bent over, there appears the abstract form and movement that carry it. But in that painting, the surface is also stripped bare: no longer power, but void. Does abstraction of any kind reach far enough to say death?

–José Luis Barrios