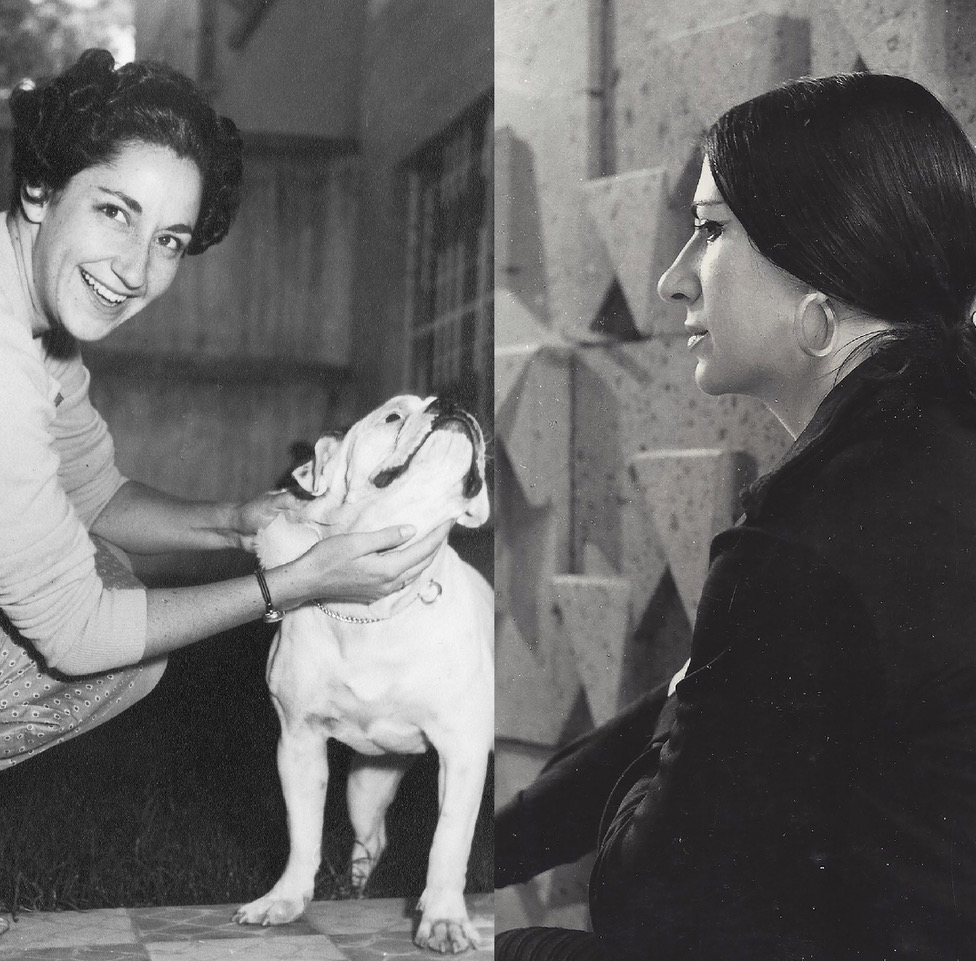

Ángela Gurría & Helen Escobedo

Conceiving the Sculptural, Inhabiting the Public

Exhibition

-> May 24 2025 – Aug 23 2025

Proyectos Monclova presenta Conceiving the Sculptural, Inhabiting the Public by Ángela Gurría and Helen Escobedo. The exhibition is dedicated to the work of these two foundational figures in twentieth-century Mexican sculpture. It explores the creative processes behind their medium-scale sculptural works and their ambitious public art projects. It traces their critically engaged sculptural practices through a formal and material lens.

In the 1960s, the edges of Mexico City were mapped out on the basis of the main thoroughfares, which were continuously built to keep up with the transportation needs of an ever-developing population. This happened specifically with the Anillo Periférico (Ring Road), the laying of which initially involved marking out a territory, even as it subsequently contributed to the expansion of the city itself. At the time, the architects and artists who were part of the cultural ecosystem championed the visual and spatial modification of the megalopolis based on their pictorial, sculptural, and architectural projects. That was the context in which the output of the Mexican sculptors Ángela Gurría (1929–2023) and Helen Escobedo (1934–2010) was inscribed, as they developed their work in such disciplines as drawing, painting, and small- and medium-format sculpture. Nevertheless, the work of these two artists was renowned more for the way it unfolded in the creation of monumental and public sculpture in Mexico. One can identify in their work an abiding interest in the effects of the city’s exorbitant growth, like overpopulation and the increase in motor vehicles as well as air, noise, and visual pollution.

In the late 1960s, sculptors started emphasizing spatiality over visual language,¹ which was very relevant a decade earlier with the inclusion of visual artists in the creation of University City in southern Mexico City. Ángela Gurría’s and Helen Escobedo’s production took place in the wake of the debate about geometrical abstraction in opposition to the figuration and social realism² upheld by the artists of the Mexican School of Painting. In this way, abstraction, materiality, and space gained steam in sculptural production, pushing aside representation, figuration, and themes with a historical bent. As artists, Gurría and Escobedo penetrated a sculptural world that was regarded as masculine, due primarily to the use of heavy, inflexible materials, along with the use of tools that required a certain degree of physical strength.³ Both sculptors overcame certain boundaries by persevering in their sculptural practice.

– Vera Castillo

1: Rita Eder, “Transformaciones y transgresiones: Dos o tres ideas sobre la obra de Helen Escobedo,” in Pasajes: Helen Escobedo, ed. Amalia Benavides, Irela Gonzaga, Magali Lara (UNAM, 2011), 11.

2: Daniel Garza Usabiaga, “Ángela Gurría: Segunda naturaleza,” in Ángela Gurría: Segunda naturaleza (Museo de Arte e Historia de Guanajuato, 2022), 19.

3: On this, Roselín Rodríguez Espinosa recuperates a comment of Rufino Tamayo’s about Ángela Gurría’s work published in the newspaper Excélsior in 1970, relative to an exhibition by the artist: “I’m surprised; Ángela Gurría’s exhibition strikes me as very surprising. I met her just a few days ago, and found the young woman enchanting, that fragility she has, it seems to me like it doesn’t correspond to the robustness of her work, but what is certain is that I’m surprised.” Roselín Rodríguez Espinosa, “A. de Ángela Gurría: La invención de un lugar para una mujer escultora de obras monumentales en el espacio público,” in Ángela Gurría: Señales (INBAL, 2024), 127.