Review

cyber(☁️)punk: About (be water) in 'Aguas verdaderas' by Federico Pérez Villoro

by Maya Renée Escárcega

At Ayer Ayer

Reading time

7 min

Periodically, the flow would enter the houses situated in the valley of a river, any river. Debris and unpleasant smells from floods contributed to the ease of disease transmission. The people living on the floodplain were referred to as "varzeanos," a pejorative term for the most disadvantaged parts of the city. Even though this occurred in Brazil toward the end of the 19th century—when cleanliness, urbanization, and progress were discussed— today we can recognize a similar problem in the Lerma and Santiago rivers, which are located in Federico Pérez Villoro's hometown. Aguas Verdaderas does not discuss the flobal river system, not event the continental one, but it manages to capture the history of maps, rivers, and civilizations, beginning with their individual meanders.

Consistent in its processes, the project presents a field study carried out on the Tieté River in Pivô Pesquisa, Brazil, in 2023 through writings, installations, and digital artifacts. Its waters, "of truth", as per its original name Añembý in Tupi-Guarani, flow in the opposite way into the country's interior, traversing both the state and the megacity of São Paulo.

Images that drink from the cartographic source are both static and moving, yet technological components interfere to disclose, disrupt, and physicalize the gaze in order to protest the brutality it inflicts upon the bodies (of water). Industrialization processes turned the Tieté River into a device that generates electricity. Its logics were inverted, cleaned up, and destabilized, according to the modern project.

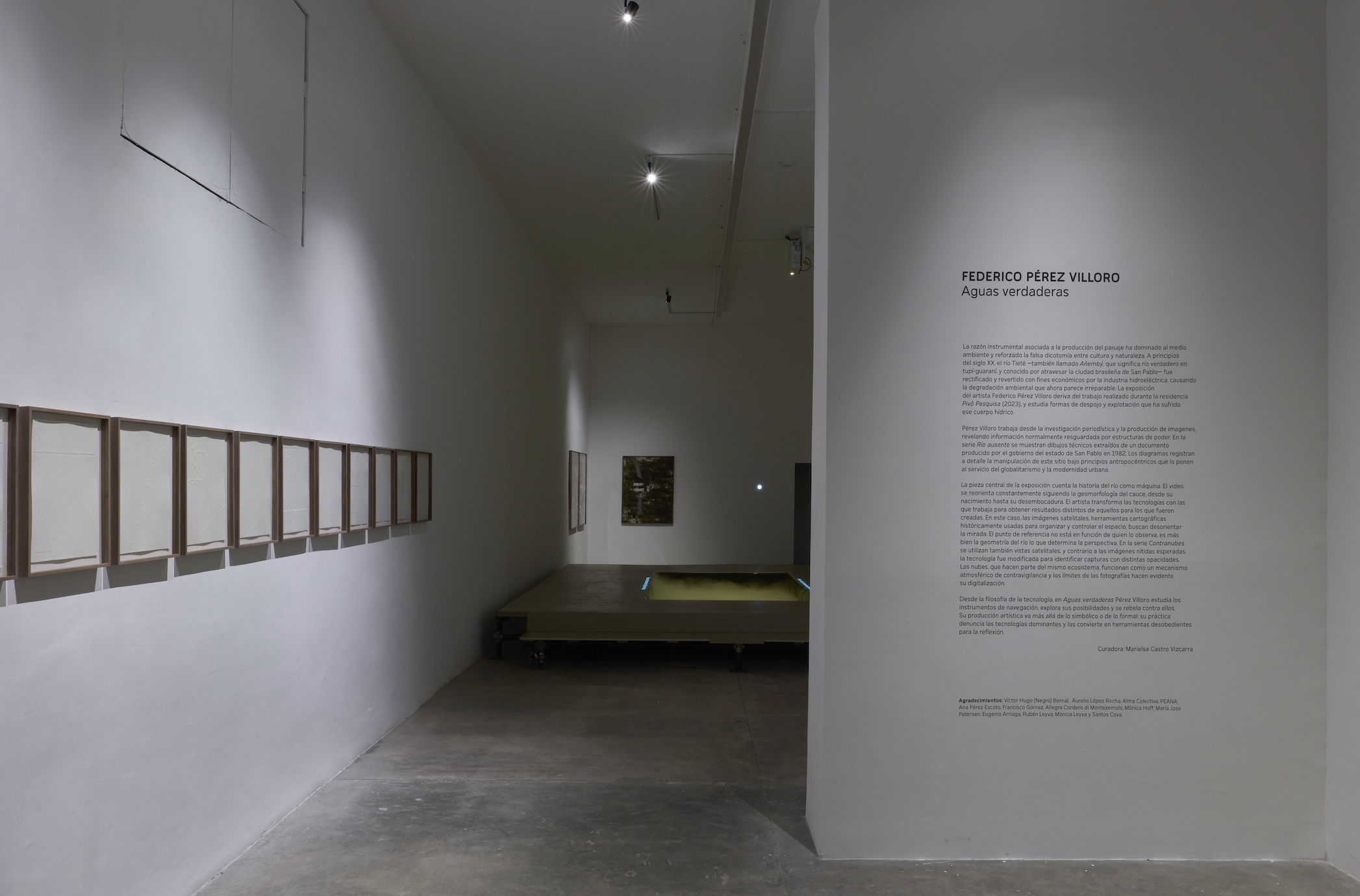

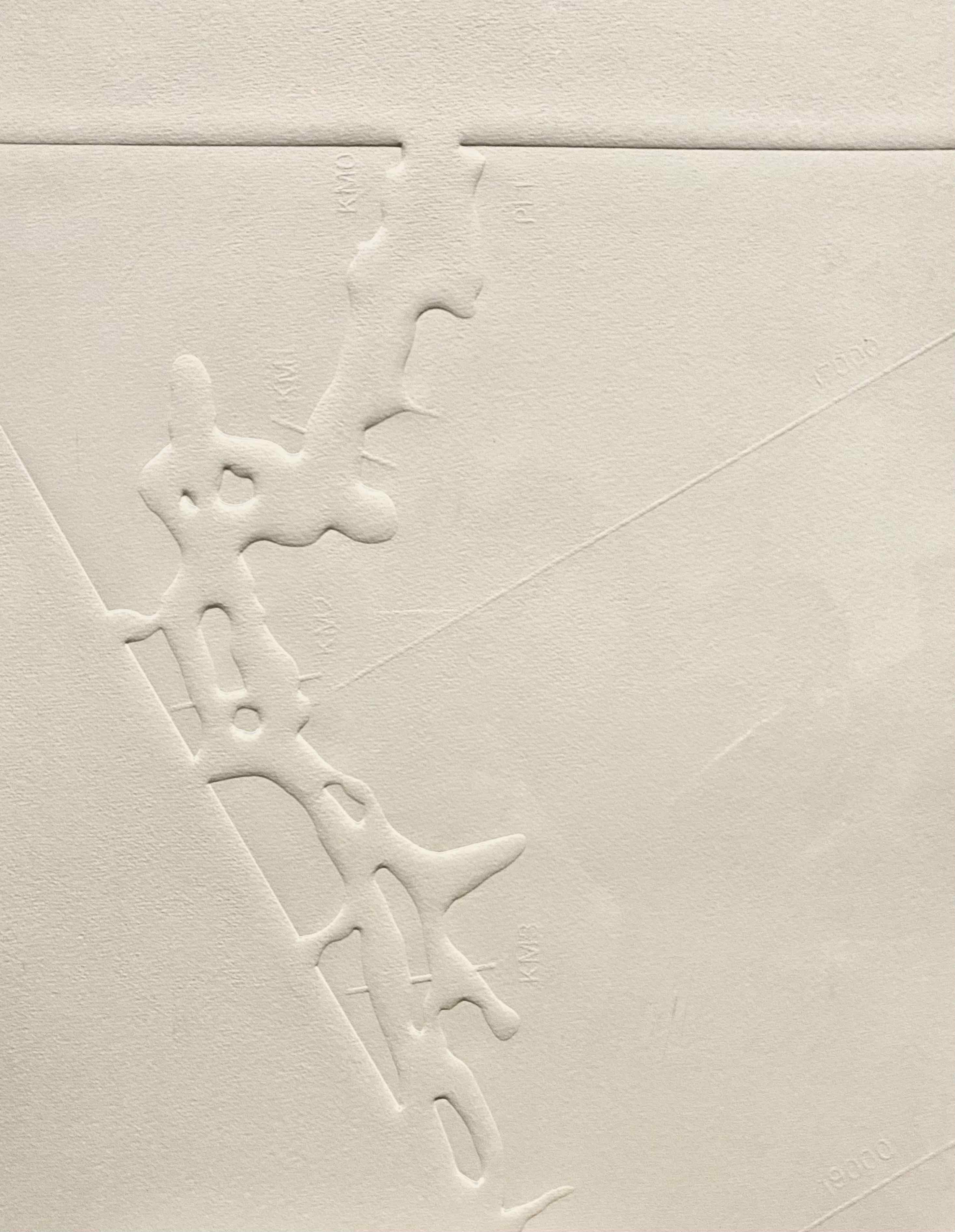

The show in Ayer is introduced with fourteen off white cotton sheets. If the dispossession weren't tangible and physical, it would be absolute. There is a weave or a spider's web engraved on each relief. Each ramification informs the desktop nature of the cartographic diagrams in the publication Comportamento Hidráulico do Rio Tietê [Hydraulic Behavior of the Tietê River] that Pérez Villoro took as the basis for Río ausente (2024). Utilizing both scientific and administrative criteria, the riverbed was altered, treating the river as a functional technological entity in the context of urban development.

The river's geometry and corporeality are initially demonstrated by the reliefs. These aren't lines; rather, they're spider webs that reach into the earth, the subsurface, and the sky—the latter being a characteristic of the Amazon. La máquina (2024), a video installation that was conceptualized as a video essay, is the focal point of both the project and the exhibition space. A movable platform encloses a hydraulic structure with a humidifier system that creates a steam bed. Projected onto the layer is a film consisting of still satellite photos, whose perspective and orientation mirror the geometry of the river from its source in Salesópolis, São Paulo, to its mouth at the Paraná River. In this tale by Pérez Villoro, a voice juxtaposed on a sound piece designed by Brazilian musician and geographer Luisa Lemgruber is layered to tell the story of a machine that expands until it loses its parts. It incorporates the viewpoint of the spiders, who indicate that the water is safe to drink by walking across it. When the spiders walk away, dispossession transforms from a methodology to an archetype.

The gaze is embodied in the satelidad perspective. On the one hand, there is the body of the river itself: the machine is a living thing, breathing and redistributing the picture throughout the mist. The Big Brother body, with its hunched neck, scrutinizing every move, is present on the opposite side. The vapor is now the clouds, not the river's body interacting with the onlooker. Point of view: you are a man-made satellite.

The Be Water concept, which Bruce Lee¹ popularized, served as the organizational foundation for the 2019 Hong Kong protests. Be Water was a decentralized political movement that was difficult to contain because of its flexible techniques and group decision-making. In opposition to a facial recognition surveillance system and other monitoring instruments, demonstrators wore masks, face shields, unfolded umbrellas, and goggles. Faces and personal data served as weapons for both sides. The government enacted a legislation prohibiting the wearing of facial coverings not long before the pandemic broke out. The act of looking is an act of capturing.

Clouds are the facemasks of bodies demanding to be water. A technique used by the artist to make clouds visible in satellite images is used in Contranubes (2024), a series of four prints featuring views of the Tieté River. Each print has more blank squares than the one before it and is arranged in an alternating pattern of squares with varying opacities. The work is a counter vigilant reaction against methods of cloud masking. . In order to provide a sharp image, algorithms are applied to data that has been affected by cloudiness. We are not necessarily able to see just because the raster cloud mask is present. High resolution satellite imagery is typically not made available to the public; this serves to obscure georeferenced data that is intended only for use by military forces, government intelligence agencies, and industry analysis.

Among the twenty infrastructural interventions imposed on the river, the video installation Contranubes (in movement) (2024) features a peephole embedded in the wall that allows a close-up view of an animation with hundreds of thousands of images captured by the Landsat 9 satellite of the Três Irmãos [Three Brothers] hydroelectric plant. Right before arriving at the river mouth, a bottleneck may be seen due to the shifting grid design. Both upstream and downstream are compromised by this dam: on one side, it dries up, while on the other, it floods. Subsequently, the composition progressively becomes white; the data collection and analysis are interrupted by the vapor layer. Ultimately, the picture isn't white; absent of information, of body, of image. It is a cloud, a barrier made of intricate tissues and dispersed, fluid, anonymous organisms.

After all, when it comes to the river, everything is about scale. What Clark understands as scale disorders. The rejection of the idea of reducing God to data and the return to the hypothesis endowing humans with the ability to create and destroy everything. «The term "Anthropocene" is arguably similar to the image of Earth from space in that both imply that humans look down from afar on all other life forms.» (Hilyard, 2017 p. 32.) Thus, Aguas verdaderas is a reminder that what were once line graphs and manipulable machines are today living organisms in flux that spread, through respiration, a disease that was not self inflicted caused to beings that did not ask for it. In any case, we were unaware that the clouds were being censored.

Translated to English by Luis Sokol

¹ “Be like water making its way through cracks. Do not be assertive, but adjust to the object, and you shall find a way around or through it. If nothing within you stays rigid, outward things will disclose themselves. Empty your mind, be formless. Shapeless, like water. If you put water into a cup, it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle and it becomes the bottle. You put it in a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Now, water can flow or it can crash. Be water, my friend.”

Published on February 4 2024