Interview

You Can’t Be Both Buchona and Minimal at the Same Time: Interview with Lucía Oceguera

by Sofía Ortiz

Reading time

7 min

I don’t want to arrive at Lucía’s empty-handed, but the hour—2 in the afternoon—doesn’t inspire me to offer up the six-pack I would normally take. Instead, I bring a baguette, two avocados, and four tunas. Lucía lives with her kitty, Sombra, in a small and very tidy apartment. “The light is beautiful ” I tell her.

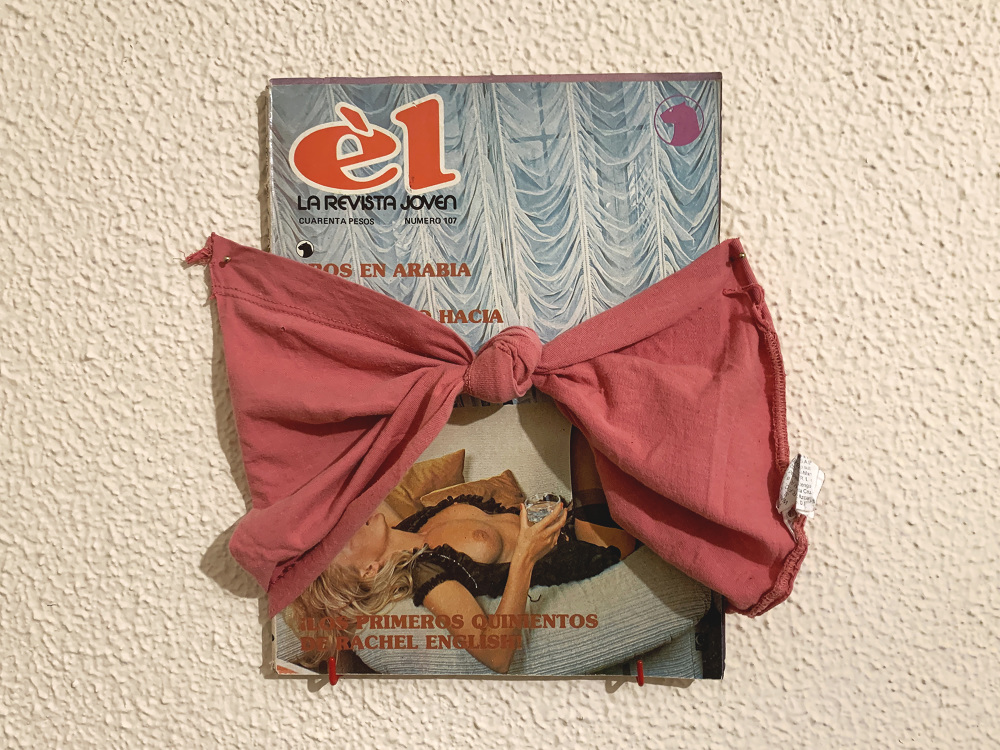

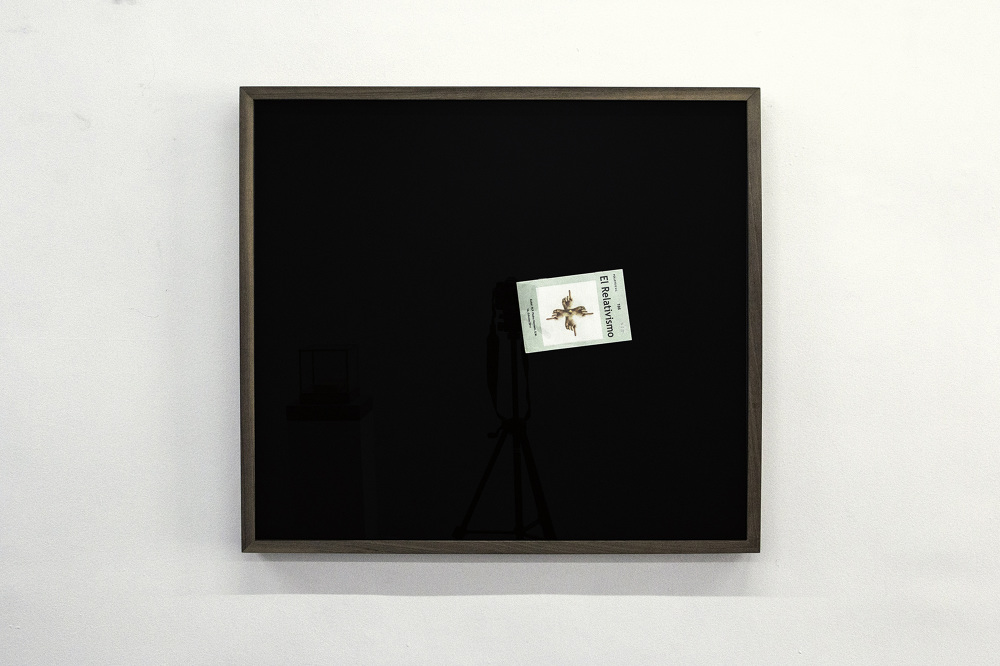

She sits in an armchair facing me. Behind her is a wall with several framed pieces: dioramas, sculptures, collages, and drawings. I’m struck by a small, faded blue brochure inside a frame too big for its dimensions. On its cover there’s a smiling couple and above them a header: “CHASTITY: A Virtue for Our Times.” Lucía found it in her sister’s bureau. There were more pamphlets, among them, “RELATIVISM” and “CELIBACY: VOCATION OR FRUSTRATION.” Their mother left them about for her daughters to find them and that’s just what Lucía did. I’m still not sure, but the framed brochure seems to be rotating.

Lucía grew up in Culiacán, surrounded by sisters and bling: Opus Dei-run schools, skinny eyebrows, women’s activity classes, dark eyeliner, diamond-studded BEBE t-shirts, Versace print jeans. “I was always going against the grain,” she tells me. I want to see the photos that testify to her dissident adolescence but she hasn’t sent them to me yet.

My first contact with Lucía was via Instagram, when she still carried the handle buchona minimal*1. “It’s a joke,” she tells me, “you can’t be both buchona and minimal at the same time.” However, it’s in just that place, between the exaggerated and the elemental, that her work unfolds. The first pieces I came to know by Lucía were cement plates with inlaid diamonds in the shape of a constellation; a purification of the northern urge for brilliance.

“It was the first time I used diamond as a material. I chose Orion because it’s the constellation that helps me to find a question mark in the stars. Since I was a little girl I would see it, it was that thing of facing upwards and saying, OK, sky, you get me, you don’t know either. I wanted the material, the cement, to hug the stone. The diamonds vary in value, some are more expensive than others. I bought them in the Mercado de Garmendia, but here they’re all worth the same and they’re all alike.”

I’m left with the idea that Lucía wants the diamonds themselves to feel embraced; I realize that she has a singular affection for objects. During our talk, she mentioned several times that she wanted to change the fate of things—that she visualizes the point of view of the objects she saves. I imagine her as a kind of Saint Francis of Assisi, rescuing trinkets instead of animals.

We’re standing in her non-studio (the second room of her apartment, a pandemic provisional space), and she places in my hand a small USB in the shape of a Malibu bottle. Right away it’s 2002—I’m in my friend’s room taking hurried shots. Similarly, the little totem to storage and alcohol takes her back to the moment she lost her virginity: thus emerges the idea for a new piece.

Lucía works by finding and translating metaphors; from an object randomly placed next to another is born an idea, which she then recognizes, catches, and brings to earth .

“My process almost always begins with cleaning; I start from an anecdote, a pebble, a ring, something that’s been at my side for a long time. In this process of ordering, one thing ends up side-by-side and something happens, an idea springs up.”

When she found the brochures in her sister’s bureau in Culiacán, she decided to turn them on their own axis, mounting them on clock motors. I turn to see “CHASTITY” and I notice that it’s turned 90 degrees since the last time I saw it, trapped in the impossibility of its circular discourse. Lucía can be empathetic with some objects, but very cruel with others. “However, my work is not something I can just force; for the same reason, it’s difficult for me to have continuity. I have to wait for an idea to come to me.” I once again see her orderly apartment and I think of Lucía waiting for her ideas, a Penelope in Santa Maria Ribera, with latex gloves instead of threads.

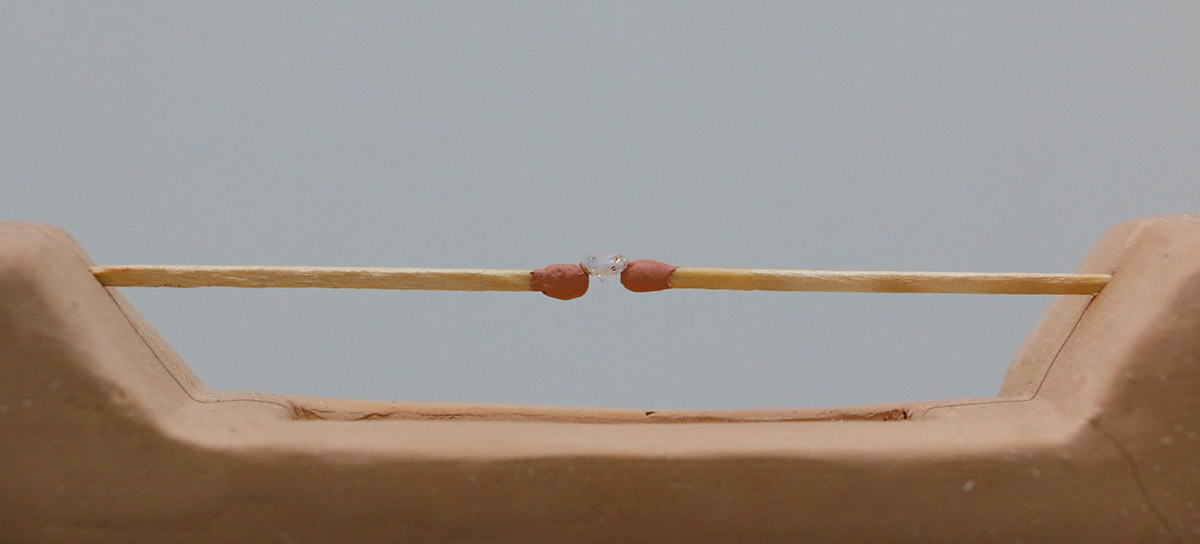

“I sent for sand from Culiacán,” she says as I examine the Malibu bottle. “I lost my virginity on the beach. I want to make a glass box, with a stained-glass window repeating the scene from the Malibu label and the song I remember playing that night.” She shows me a clean and neat diagram of the scene she has in mind. Part of her process consists in finding a way to produce her pieces, which often takes her along a winding and surprising path. She points to a sculpture with two matches holding a small diamond between its points. “I was at Casa Wabi in 2018 when I thought up that piece. I went to make the matches in Tultepec, where they make fireworks. I wanted them to be really explosive. I could only carry a few things and I took my favorite objects.” She points to another piece: the gold outline of a ten-peso coin encrusted in a pyrite fragment with two pencils whose tips meet in coin’s center.

“I look for simple gestures between objects, ones that confront each other or that coincide.”

She shows me more pieces. I’m struck by her “relativistic trophies,” tiny mockups with diverse objects: a mini blackboard, a mini Korean Coke, images of hands pointing at each other. She says that she chose these objects by searching for “relativism” in Google Images. Each mockup has its own magnifying glass; the invitation to study the absurd so seriously makes me laugh. There’s a lightness in how she arranges and executes her work, even when she tackles heavy themes. She recently began producing ceramic tombstones—we’ve really been in the presence of death lately,” she tells me—with phrases like “patience” or “wait slowly but move forward without delay.” The graves are small and imperfect, dark and at the same time rounded like a Comic Sans typeface.

“These last few months have been very weird, but I recognize that the pieces I like most come out of these moments of crisis.”

She shows me one of the pieces she’ll never sell; a black-and-white photo of some brush on which she embroidered colorful plants. “It’s the photo of where they found the body of my first boyfriend, the same one from the beach the Malibu. The idea was to change that last photo of him and to cover the body with the embroidered weed so it would be disguised.”

To see Lucía’s work is to know her story, her non-conformity as well as her tenderness for the world around her. We joke that she came out of the closet in 2016 with her solo show at the Museo de Sinaloa; that is, the Culiacán closet decreeing that the most fervent female desire is to have a ring on one’s finger and a couple of children in a van.

“I would give guided tours and people’s response to the work, especially among the high school girls, was much closer to the kind of discourse I wanted to convey. They understood the gesture of reducing and sophisticating the materials of their everyday life. It blew their minds to know that this was art.”

She then falls silent for a moment.

“To make art you don’t need virtue or talent…you need faith.”

What a great end to the interview, I think.

“CHASTITY” completes its rotation.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

*1: Translator’s note: buchona is a slang term for a woman associated with the excesses of narco culture and its distinctive aesthetic.

Cover picture: Lucía Oceguera, Intentional Coincidence No. 1. Courtesy of the artist and Casa Wabi

Published on January 2 2021