Review

Wendy Cabrera Rubio: La señorita Eugenesia y otros cuentos at General Expenses

by Julián Madero Islas

Reading time

6 min

I hope the angel and the monkey get confused, like two drops of dew that roll and meet on a rose petal.

—Alfonso Luis Herrera, El híbrido del hombre y el mono, 1933

The recent exhibition of Wendy Cabrera Rubio at General Expenses unfolds like an index to delve into her career, almost like a micro-retrospective. Beyond the themes addressed, Wendy summons artists, discourses, eras, techniques, and mediums, orchestrating a collaborative, intermedial, and transdisciplinary body of work. The initial feeling is like stepping into a temporal fold where the recent—and not-so-recent—past is dissected with apparent tenderness.¹

It's certainly difficult to separate the work from the artist. As Memo Martínez said at the recent Terremoto auction, "Wendy Cabrera Rubio is everywhere and more famous than Wendy Guevara." Proportion aside, it’s true that our artist is present, and her voice stands out from the crowd. Anyone who has heard Wendy speak knows the evocative reverie her musings provoke, painting and recreating scenarios on the most varied topics, which led me to wonder how I've spent my own time and when our dear friend learned all those things. Wendy, indeed, is a mediator of her own work, as well as a popularizer (of art, science, and Mexican history), director, node, and point of convergence.

Pedagogies of Cruelty

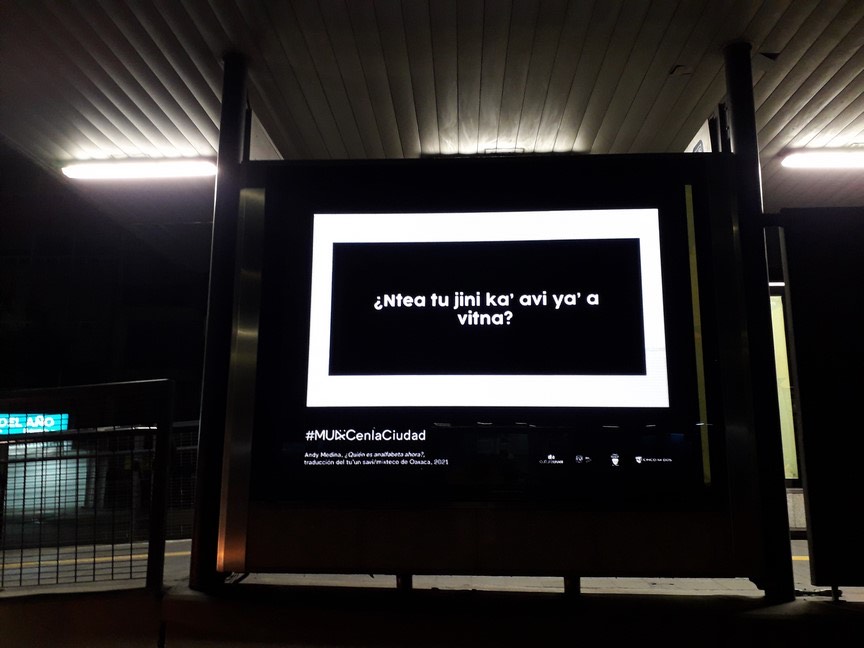

It would be convenient yet tedious to separate form from content, though here it proves exemplary. The collaborative production, carefully crafted, establishes a separation that displaces the notion of style. There is an aesthetic, of course, and a recognizable style, but these recede, allowing the objects to express their singularity. Just a step toward the content reveals its sharpness. The forms, which appear soft, tender, and didactic, reveal themselves—upon informed reading—as dark, contradictory, and biting. Their apparent didacticism, in my opinion, aligns them with Andy Medina's series ¿Quién es el/la ignorante ahora? [Who’s the Ignorant One Now?]². Both bodies of work highlight the hidden violence in educational practices by appropriating and displacing the same teaching devices.

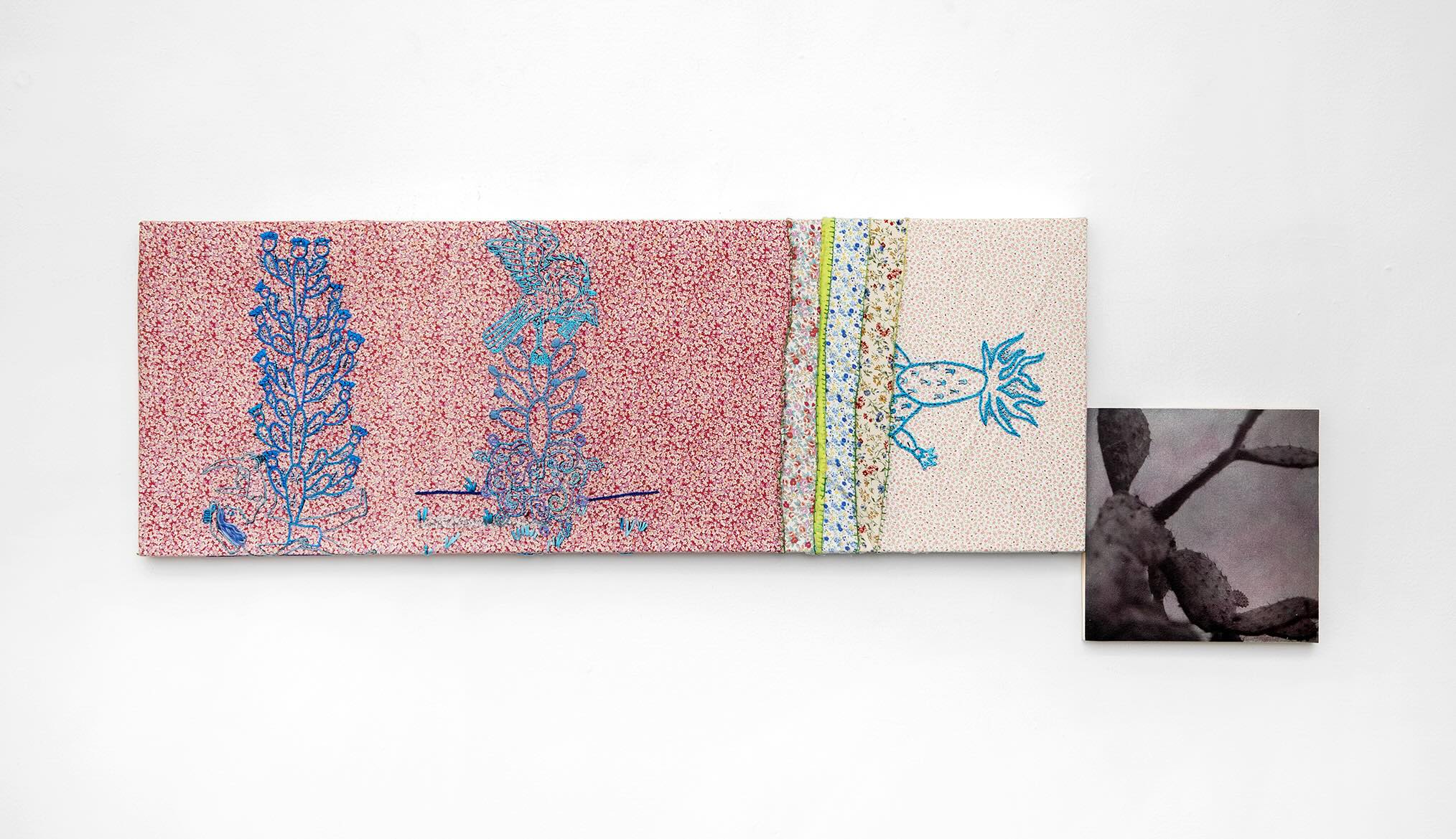

At the same time, Cabrera Rubio’s pieces, through their allegorical reconstruction of technological innovations that have accompanied colonization processes (constellations, navigation sails, food regimes, scientific cinema in Super-8, hand-colored analog photography, patchwork, plasmogeny, education, patents…), expose their epistemic, social, and environmental implications, revealing the horror lurking in the scientific discourses of remote—and not-so-remote—eras. In this regard, it’s significant that the Zapatista communiqué Sobre el tema: La Tormenta y el Día Después [On the Subject: The Storm and the Day After] from October 11 (the day before Miss Eugenics and Other Stories opened) raises the question: “To what extent do modern technologies already control—or not—artistic creation and scientific research?”³

Oh, Daughter, I Want a French Son-in-Law

One of the main figures in the exhibition is biologist and naturalist Alfonso Luis Herrera (1868-1942), a pioneer in Mexico in the study of the evolution of living beings and founder of the Chapultepec Zoo. Wendy captures his dramatic contradictions. In Resurrecting the Past: Animality and Chemical Ethics in Alfonso L. Herrera, Franz Kafka, and Gustave Flaubert⁴, a collaboration with Clemente Castor, Mauricio Guillén and Antonio Ponce, the artist recreates a visit by the scientist to the zoo, where he recites dark passages in which Kafka and Flaubert fantasize about a hybrid between man and monkey. Even more deranged is Herrera’s own text, El híbrido del hombre y el mono [The Hybrid of Man and Monkey], in which he suggests creating a hybrid by intoxicating and raping a female primate. A singular experiment that leaves us dumbfounded: on-screen, we see a white-man-in-white-mask performing the solemn motions of fertilization between test tubes and petri dishes. Herrera becomes a symbol of early 20th-century white aspirationism, and the genetic mix serves as a metaphor for the progressive disdain toward indigenous cultures.

During the Porfiriato era, discourses abounded about integrating indigenous peoples into modern Mexico. There was talk of “attracting immigrants to improve the race.” As Bonfil Batalla pointed out: “In Mexico, to civilize always means to de-Indianize, to impose the West.”⁵ Faced with the failure of the desired race improvement through intermarriage with foreigners, eugenics emerged as a new alternative. Education—soft eugenics—became an instrument of control and indoctrination into the dominant culture. “De-Indianization is not the result of biological miscegenation, but of the action of ethnocidal forces that ultimately prevent the historical continuity of a people as a socially and culturally differentiated unit.”⁶

“Independence Made Us Spaniards to the Indians”

Given the historical nature of her research, the adoption of various discourses, the collaboration between disciplines, and the integration of media, Wendy Cabrera Rubio's work resonates with the stagings of the collective Lagartijas tiradas al sol. I think of Centromérica (2024), where Luisa Pardo and Lázaro Gabino Rodríguez portray themselves, dramatizing their journey through Central America and the vicissitudes they encountered. But what’s most revealing—because it’s contradictory and problematic—is that Luisa and Gabino present themselves, in their innocent—perhaps naïve—approach to the political and social reality of the region, as a pair of gringos visiting Mexico: the adventurous spirit of settlers and their tendency to exoticize the foreign. Mexico, then, is the North America of Central America. And how uncomfortable it is to recognize ourselves in that mirror. I celebrate, in the (un)fortunate case of Centroamérica, the incorporation of its inherent contradictions and the exhibition of its shameful traits, not in a confessional tone, but plainly and bitterly.

All in all, I believe that the power of art, unlike other forms of knowledge, lies in the formal negotiation of its contradictions (poetic, affective, political, ethical). In this gap, Wendy Cabrera’s exhibition at General Expenses proves rich and provocative, confronting us with our own whiteness, with the unbearable tendency of the middle class—particularly those in the art and academic worlds—to live like gringos in their consumption habits (cultural and dietary), in academic papers, festivals, and entertainment circuits (including galleries). Wendy’s work rewinds the tape of neo-colonization to show us in slow motion the mechanism we are all part of.

Translated to English by Luis Sokol

1: The curatorship of La señorita Eugenesia y otros cuentos is by Jairo Hoyos Galvis. The hall text is by Pablo Arredondo Vera. Collaborations were made with Patricia Rubio, Mauricio Guillén, Eugenia Martínez, Silvestre Borgatello, Clemente Castor, Svetlana González, Antonio Ponce, Javier Fresneda and José Luis Cuevas.

2: This series, which the artist has developed since 2015, is made up of the translation of the phrase “¿Quién es el/la ignorante [illiterate] ahora?” into languages of different ethnic groups. In 2021, the series was deployed in CDMX parabuses. Likewise, the piece “LII QUI GANNALU' / You don't know”, shows the phrase on a blackboard, in front of a “lame” desk supported by books.

3: El Capitán, “Sobre el tema: La Tormenta y el Día Después. Postface. First PArt. La Hipótesis (¿o era la hipotenusa?)”, published on 10/11/2024. https://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2024/10/11/sobre-el-tema-la-tormenta-y-el-dia-despues-postfacio-primera-parte-la-hipotesis-o-era-la-hipotenusa/ (23/10/2024)

4: S-8mm film and I-ph ProRes files transferred to HD digital projection, 2024.

5: Guillermo Bonfil Batalla, México profundo: Una civilización negada, (México: Editorial Grijalbo: 1990), 154, 158.

6: Ibid, 42.

Published on November 17 2024