Essay

We Are the World of Those Gestures: On 'Atlas Western' by Chantal Peñalosa

by Sandra Sánchez

At MUAC

Reading time

10 min

This room that is cold and dark—though not as much as a movie theater—as well as spacious and with a single bench in the center. A crisp voice, one that is artificial out of training, and which is not the artist’s, and that narrates and fills every pore in the room. I think of Chris Marker, of his voice without drama, of the essay-turned-moving image, of impotence: resignation to climax. Likewise the decision not to want to equate sound and its grammars of meaning with the image in order to tell a story. The invitation to thought rather than to linearity. Harun Farocki comes to mind, as was also once on view in this museum. Thinking is taking risks, traveling the dirt road knowing well its zigzag, the possible inoperability and the (already heroic) failure to tell what happened just as it happened: embracing invention, engaging in suspicion, knowing oneself and knowing one’s fate, perhaps only momentarily.

Atlas Western is an audiovisual essay based on a movie set: Cine Pueblo, built on the outskirts of Tecate, Baja California, with of aim of recreating the Old West. It is something that Chantal Peñalosa approaches as though it were a three-dimensional archive that opens, accommodates, analyzes, and reassembles itself for us, here and now. The landscape was the same on both sides / Toward the southern border everything was cheaper, more attractive.*1 A saloon, a police station, a bank, and other settings. The project did not work out: the western was in decline. The artist’s thought revolves around misfortune. The feeling of planning a surprise party for a boss who doesn’t show up, who doesn’t mind not showing up: gifts left on the table. The disparity between what was planned and the speed of a desire that has moved elsewhere, to another image.

The illusion of the cinematic genre can be heard throughout the film: dialogues, tones, platitudes. The very old and disgusting patriarchal gesture of defeating the other at the cost of their life. The mirage of honor. The duels sustaining a proper name because the name itself rests on the curse of the individual and not on the alliance of a collective agency.

I am irritated by cowboy laugher. I am irritated by the hypostasis of dignity (and its recesses of beauty), as well as by bland death. I am exasperated by the imaginary of guns and bullets: the symbolic actualization of tragedy cloaked in manliness and decorous codes. There will be those who say with precision that the western is not one thing, or that it’s not only that, or that it’s not that all the time. But in the middle of this room, the soliloquy of the trained voice leads me to my conclusion, as when in a café you listen to a story and start connecting it to your aberrations and enthusiasms.

Meanwhile, the eyes look at the elapsed time, the time of abandonment: visible in the rags of the set. The artist has placed on the ruins some paintings/stage designs of icons of the genre, fluttering to the rhythm of the local wind. Yes, geography can be seen by the effect of air on bodies.

Chantal ventures a hypothesis: nothing was filmed in this place because the gestures escaped from the set and there was nothing left to film…the gestures migrated to everyday life…the gestures took over the public space…fallen bodies in other places…we are the world of those gestures.

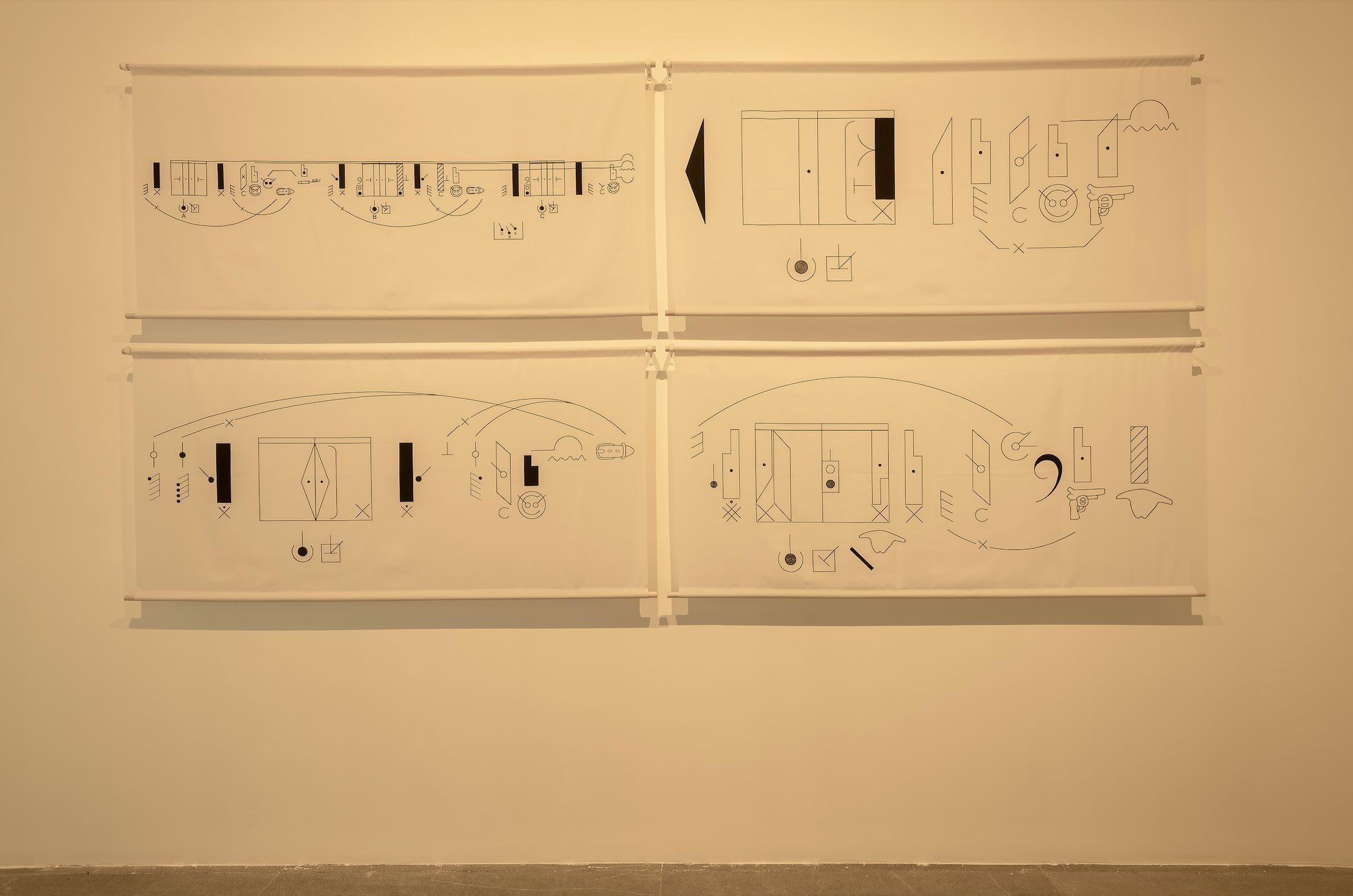

In front of the screen there are sculptures on a minimal stage. They don’t get in the way, though they are present. Sculptures on the floor and also on thin lines that function as a base. Sculptures that remind me of the work of Nairy Baghramian, though in this place they represent negative spaces that are produced when adopting the films’ poses. There are also drawings that start in the corridor and flood the room: black lines on large white surfaces diagramming scenes. The drawings write down the codification of the corporalities and movements from the Laban choreographic notation system. I cannot read their meaning: they rather appear to me as giant post-it notes that accompany the research-invention process. Of course, we are in the middle of an installation.

Boris Groys in his essay “Politics of Installation” (e-flux Journal, 2009) makes an important distinction between the figure of the curator and that of the installer. The curator “administers [the] exhibition space in the name of the public—as a representative of the public. Accordingly, the curator’s role is to safeguard [the] public character” of the space, while the installer insists on exercising the autonomy of art.

The installation operates by means of a symbolic privatization of the public space of an exhibition. It may appear to be a standard, curated exhibition, but its space is designed according to the sovereign will of an individual artist who is not supposed to publicly justify the selection of the included objects, or the organization of the installation space as a whole.

The installation can be thought of as a democratic exercise insofar as it can be accessed by anyone, whoever. Sovereignty is external to the installation’s democratic opening. The artist, when installing, sets the rules of the game. Although each spectator decides their own route and notices this or that, the passage is designed by the artist, who remains on the outside. Nevertheless, the artist does not control the diversity of experiences, but rather traces the limits: guides and decides the margins and their contents. “Here the artist acts as legislator, as a sovereign of the installation space.”*2 Groys insists: democracy is established by an act preceding it, that of the sovereign-artist.

In the installation, the sensation of flâneurie is controlled, just like in cities. The flâneur knows about the stage and the sovereign’s control, but keeps up their practice by going through the experience of walking, without wanting to buy anything and without getting into debt with signs. A sign puts you in debt when the correspondence between the signifier and the signified is hypostasized (naturalized). The sign becomes despotic: a pseudo-universal computer of a given reality, which omits happenstances and contingencies. Unidirectional sign, tyrannical sign.

Voiceover: A man leaning against the wall, staring at the landscape. Another man shoots him, the blood falls and the eyes remain open and lifeless. [...] The gestures have migrated to everyday life. The gestures have taken over public space. We are the world of those gestures. [...] I can imagine their reservations, their falls; they remain in force in other bodies; on the street and on the news.

These are the genres: fiction and non-fiction, although mimesis knows no genres. One learns how to love, to kiss, to configure one’s own name, all in the cinema: in novels, in movies, in porn, in TV series, in telenovelas, in advertising… We participate in (we consume) the articulations prepared for by the sovereign: artist, marketer, president. There, on the stage, the symbols are incarnated until they circulate in the performance of life itself, in the body and its daily images (identifications). Perhaps the western makes me suspicious because I didn’t grow up around its gestures. Because every time I see a gun my skin bristles and I feel frightened.

Peñalosa goes to Cine Pueblo and in the sovereignty of her practice shows us her use of archives, her childhood memory, her careful selection, her sequences, her cuts, her montage, and, above all, her reading: we are the world of those gestures. The western was no longer necessary because it came to life. A suspicion that critical theory already had: on the one hand, critical art, and on the other, the spectacle, mass consumption taking us away from emancipation. But repressing is useless—we know that before repression comes repetition: the return of the real is imminent. Without indicating the symptom, Freud realized that it was useless to tell the analysand the lattice of one’s story.

“What does the artist do with her sovereignty?” I ask myself after seeing Atlas Western. In this case, I think that what Chantal is working on is the reverse of fantasy, the theatrical rigging—and its failure. What happens to us? What are we summoned to do? Without a doubt to point out the seam, the perverse and/or hazardous production of deception. To work with the language that carries it out as well as its consequences in intimacy. The operation of the establishment of reality by the sovereign operation of the film spreads across life.

There are also murmurs about what is left without an image on the big screen, the infinite sadness of our wars: poverty, drug trafficking, inhumane conditions for migrants, femicides… I can imagine their reservations, their falls; they remain in force in other bodies; on the street and on the news. There is no image that the fantasy of a linear and moral story can produce: with its good and bad (as some TV series do), with its defined alliances and its possibility of exit. And it’s not that drug trafficking and other types of violence do not produce their images, since they do—they horrify us, we shut them out—but that these images continue to be designed from the perspective of the despot, the master, the violator. Arms outstretched over one’s own blood.

At the end of the film the sounds of the bullets are happy, heroic screams, as well as sounds of adventure: sounds of horses, rhythm, and music. That is something that belongs to cinema and, in its escape, to a certain performance of life: it soaks up signs and desires. The grammar of the western (or of any genre) is a set of tools arranged in order to dress—consciously or unconsciously—a subjectivity.

I think of a playwright and of classes on Shakespeare. After the tragedy, before the audience departs, a dancer would come out to calm the spirits, to accentuate the fantasy of the staging. One leaves Atlas Western and screams are heard in the corners of cities. No suture is possible. Neither is there nihilism, since we can’t afford that luxury.

Second hypothesis: we know that the path is rendered all the same in its repetitions. Thus, we can anticipate a small deviation, like in Caminhando (1963) by Lygia Clark, under the eyes of Suely Rolnik. Constructing (deconstructing and unlearning, without the promise of effectiveness): no longer separating intimacy from the social. Whispering and spreading rumors that alter, in their transit, the stories in which the one is exchanged for the common. Writing with 4, 6, 8 hands. Activisms and vitalisms in the midst of pain. A conception of political action that admits without fault that we cannot all the time be in the middle of political action since the body needs care—and that too is political action.

Hevda says in “Sick Woman Theory” that “the most anti-capitalist protest is to care for another and to care for yourself [...] To take seriously each other’s vulnerability and fragility and precarity […].” Giving up sovereignty? Rehearsing cracked autonomies? “A world where many worlds fit.”*3 Sovereignizing collectively? Flâneurie, outstretched hands, and interactions without debt. Amidst the screams, the possibility of working together, accompanied by inescapable failures.

Atlas Western can be seen in room 3 of the Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) until March 27, 2022. The curator is Amanda de la Garza.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

*1: Italics from this point on are translations of fragments of the voice in the piece.

*2: All quotations by Groys are from “Politics of Installation.”

*3: Translator’s note: this is a translation of the Zapatista slogan “Un mundo donde quepan muchos mundos.”

Published on December 4 2021