Review

A buzzing light. On Elfie Semotan: 'Color y Carne / Color and Flesh' in Campeche

by Mariel Vela

Reading time

6 min

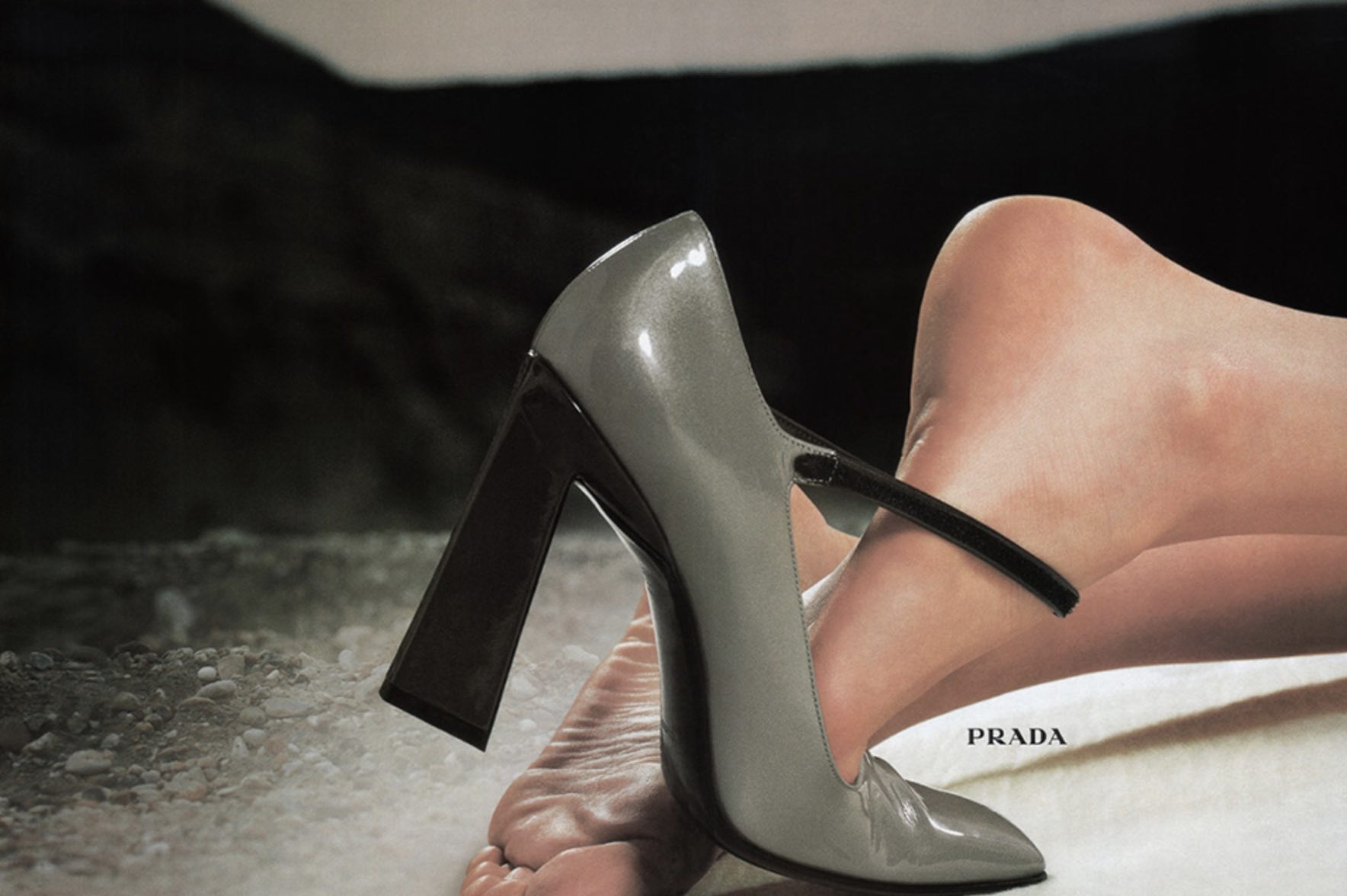

When I was a teenager my love for images was deeply cultivated through fashion magazines. It was within those pages that I intuitively began to develop a sense of proportion, an appreciation for color and most of all, a feeling for light. The shiny pages in them have that finish due to a mixture of polymers that add certain qualities to the paper they are printed on, creating an almost weightless flip, that silky surface smoothness. Due to a reduced ink absorbency, the polymers literally push the photographs to the surface, making it possible for our eyeballs to glide coolly over them. I would tear out pages to put up on the walls of my room and gaze at them while doing homework or getting ready for school. Through this exercise I learned about space flow, montage, and juxtaposition, about the velocity at which desire moves through the act of seeing. A fern green Mary-Jane shoe balanced on the arch of Angela Lindvall’s foot by a thin leather strap in Prada´s 1998 Fall/Winter campaign. Daria Werbowy floating inside a candy pink tub, with chunks of jade on her wrists for Céline. Gisele Bundchen and Rhea Durham tackling each other with oily, glittery skin wrapped in denim for Dior. How badly I wanted to look at the world through those frameless red and yellow sunglasses.

Elfie Semotan is an Austrian photographer mostly known for her commercial work in fashion. Aside from numerous solo exhibitions, particularly in Vienna, her photographs have also appeared in group exhibitions alongside Pieter Bruegel and Cindy Sherman (who, I just found out, produced a series of photographs for Comme des Garçons in 1994). Elfie Semotan: Color y Carne / Color and Flesh was inaugurated in early November in Campeche, the first gallery to present her work in Mexico. This project, organized by independent curators Úrsula Dávila-Villa and Anna Stotthart, features a selection of Semotan’s landscapes, portraits, and still lifes spanning 1990 to 2020.

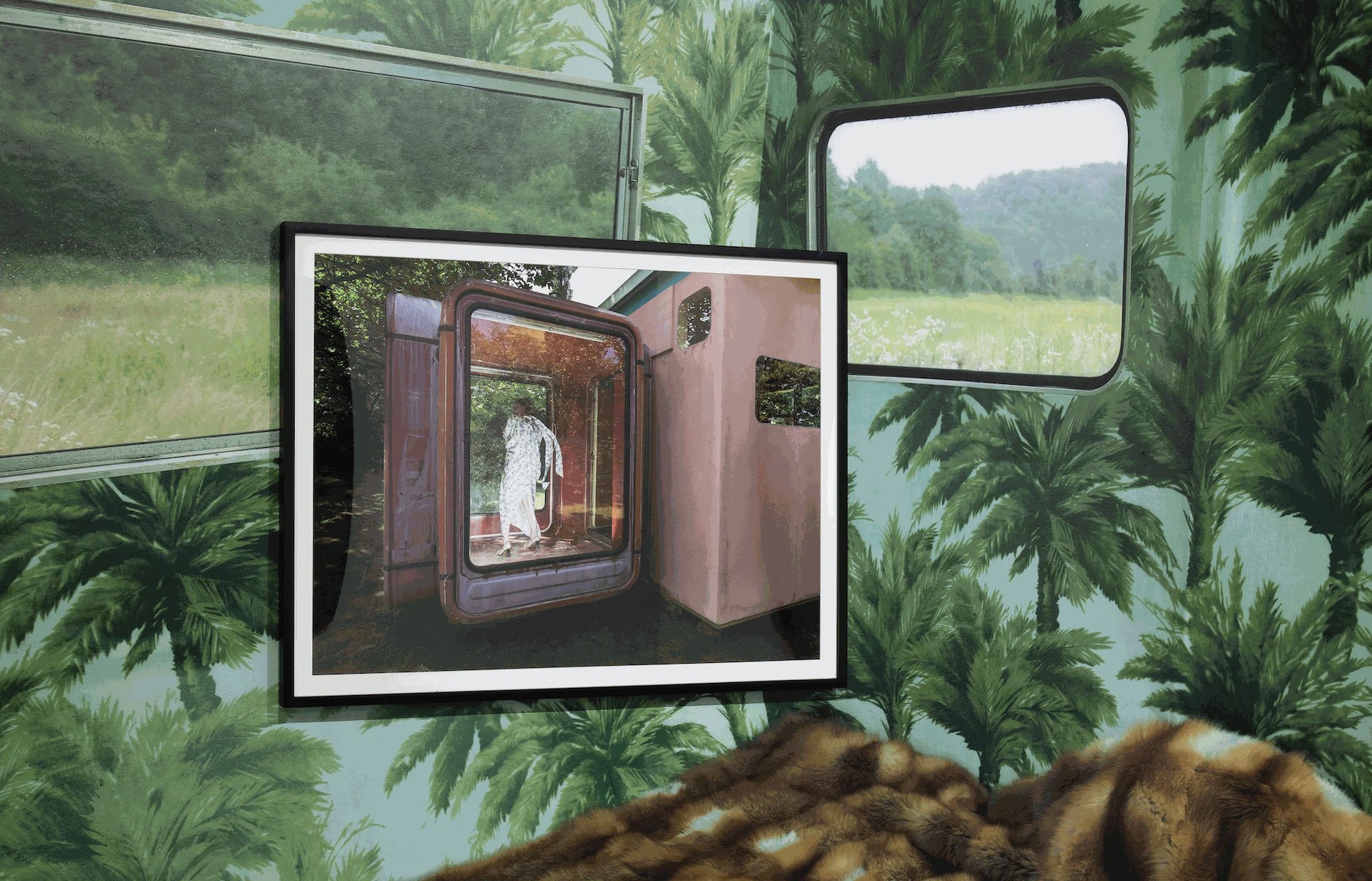

The first thought that arises when I step into the gallery is that Elfie Semotan’s photographs are deeply personal. All of them. Energy fills the space with an alluring hum as the body wanders from one to the next, entering and exiting several open-ended narratives at the same time. Anna Stotthart’s decision not to separate the more intimate work from her commercial work*1 helps evidence the absurd opposition we categorically impose between those two apparently distant points of view for photographers. In Color y Carne / Color and Flesh natural light is the diaphanous glue that creates a common sensation throughout the exhibition, for it is precisely the element that creates flesh out of everything it touches: silk, feathers, plastic, diamonds, wallpaper, fur.

Elfie Semotan’s expansive oeuvre, extending over the past fifty years—3,000 boxes of negatives, 2,000 boxes of color slides and 30 TB of digital material—is still being carefully archived by her daughter in-law, curator Úrsula Dávila-Villa. Even the “bad” prints, the overexposed and scratched ones that Semotan treasures precisely for these material defects must be kept, making the task of cataloging her work even more intricate. This is how I learned that my favorite image in the show, an overexposed self-portrait, was rephotographed years later with three masks and reprinted on a smooth kind of Japanese paper. The masks appear to have human hair and smile luridly against Semotan’s sun-streamed face. When I tried to take a picture with my phone it caught my reflection; the five of us staring into each other, across time.

On the left wall there is a dialogue between horizontal and vertical planes, between concrete and a forest. A still-life of construction debris is the kind of found scene where Semotan must have walked right into that Vermeer-light pouring towards the rocks. A contrast with the photograph on its left, a theater fashioned amidst trees producing an artificial landscape. In the first photograph there is a salmon pink rag lying crumpled between the gray trash, and in the second a thick dusty rose curtain that is wrapped around a rough tree bark with another fabric made of iridescent pink, green, and golden silk. I think of Aldous Huxley, his obsession with the gray flannel of his trousers during a mescaline trip: “Civilized human beings wear clothes, therefore there can be no portraiture, no mythological or historical storytelling without representations of folded textiles. But though it may account for the origins, mere tailoring can never explain the luxuriant development of drapery as a major theme of all the plastic arts. Artists, it is obvious, have always loved drapery for its own sake–or, rather, for their own.”*2

The series Untitled (inspired by John Coplans), have the sculptural quality of the work it is referencing, but what was frankness in Coplan’s naked aging body here becomes a sleeker study of proportions: two pinky fingers interlace, emphasizing the elegant tendons of the wrists, both adorned with chains of small metallic beads, while a choker of fine threads envelops silver strands of hair around the neck and a perfectly cut diamond crowns a knuckle; a diamond is photographed like a face.

Naked Torso with Feathers has that backstage voyeuristic quality. A model, seeming to be cast in marble due to the grainy quality of the print, looks down to the hand on her hip bone, fitting or removing a garment. Helmut Lang’s portrait, which lingers closely, reminds me of his use of unconventional materials such as rubber, metallic fabrics, and feathers during the nineties and early aughts. Close friends and collaborators, Semotan and Lang would influence each other’s work constantly. I googled old runway shots where she walked for several of his shows, alongside Stella Tennant, Kate Moss, Amber Valletta, Kirsten Owen and other muses, all dressed in beautiful minimalist designs. When asked about those times, Kirsten Owen shared her memories of the 1998 collection: “If I can quote Juergen Teller,” she replied, “it was more of a smell than a memory of raw concrete and hi-fi. A buzz.”*3 In a lot of Semotan’s photographs I feel that buzz. A sensation that goes beyond the visual, a kind of music.

*1: Many of the observations gathered here from the perspectives of independent curators Úrsula Dávila-Villa and Anne Stothart can be listened to in the recorded conversation: Radicalidad y Permanencia En Legados Artísticos: Cecilia Vicuña, Elfie Semotan y Lorraine O´Grady, originally held in Campeche:

*2: Aldous Huxley. The Doors of Perception. New York: Perennial Classics, HarperCollins, 2004. p, 31.

*3: Sarah Mower. Helmut Lang for Vogue Magazine. September 1, 2015: https://www.vogue.com/article/vogue-runway-designer-helmut-lang-90s

Published on December 23 2022