Interview

A Kind of Administrative Situationist Dérive: Interview with Carolina Magis

by Sofía Ortiz

Reading time

11 min

Dear Carolina,

I had the impulse to begin this email by saying, “I hope this finds you well,” but what came to mind almost immediately are all the memes imagining how an email actually finds us. It’s better that I tell you that in writing this I find myself in my studio, trying to channel Virgo’s organizing energy: Would you be interested in doing an interview for ONDA MX?

Dear Sofía,

Your email finds me sitting in my purple chair, looking at my wooden desk; I’ve got a pink box on my left, next to a very yellow UHU glue, which in turn is next to a green case, further back there’s a not-so-yellow glass that holds, among other things, two orange scissors, on the right there’s a transparent glass and behind it little pink phosphorescent papers, next to a mountain of notebooks holding my first collage, then a blue notebook and, finally, my hands writing this email on a silver computer and an incredibly white screen.

Reading your proposal, I love the idea of exchanging words and images.

When do we begin? How do we begin?

Dear Carolina,

It seems to me very apt that you describe all the colors on your desk; I think that in your work there’s a trend towards, not to say fixation with, saturated and artificial colors. Even when you take photos of flowers, you seem to choose ones that tend towards the chemical: intense purples and fiery oranges. What also really comes to mind is your use of confetti as a material, and I wonder how that interest came about and what it points towards.

Dear Sofía:

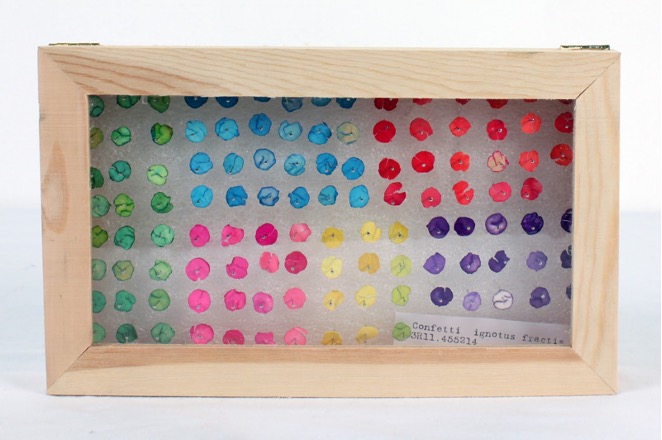

Color has always been a very natural attraction for me. Slowly, throughout my career as an artist, I’ve come to understand why. At the beginning, when I was in my fifth semester at La Esmeralda [the National School of Painting, Sculpture, and Printmaking], Sofía Táboas assigned us to do a performance. I grabbed a bag of confettï; I grabbed it intuitively because it was a lot of very fast color, plus it was an inherently happy material. It was already there, it already existed, it already meant something. The performance consisted of sorting it by color in front of all the classmates, slowly, very slowly. Once it was sorted, I put it in glasses and then I served them boiling water. Immediately, each tiny mountain of confettï released its color and saturated each of the containers with purple, yellow, pink, blue, green. The performance ended when I poured a tiny sugar cube into each glass.

At that time in my life, confettï was also snow, a kind of inexpensive snow: much more fun, much more ours than that snow that I hadn’t come to know. It was a spectacle that lasted for a little bit and from which a whole lot was expected.

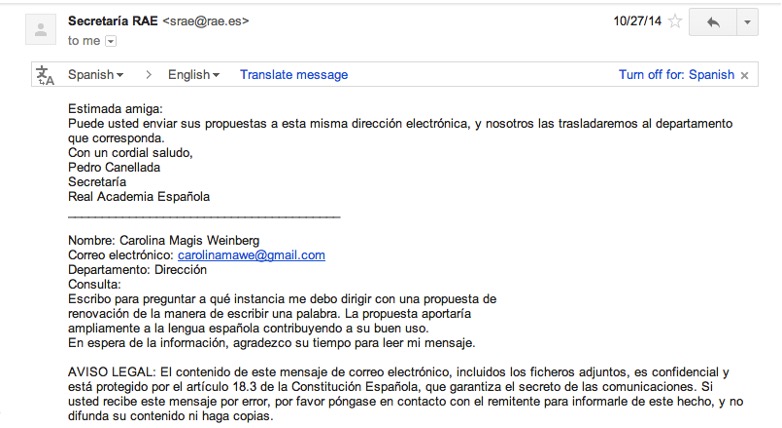

Then I studied for a master’s degree at the California College of the Arts, in San Francisco. I arrived wanting to talk about snow, desire, and symbols. But the context accented me, and I, in response, made a piece that consisted of sending a letter to the Royal Academy of the Spanish Language asking them to put an umlaut on the word confettï. My request was very formal; I made it in 2014 and I’m still waiting on an answer. The petition asked them to add a typographic mark that would visually emulate what the word represents, a proposal for expanding the term’s autological character. The issue became a matter of language, but not only that, also one of oppression and marginalization: that minimum that can end up undoing the system, breaking in from the minuscule, from the festive. That which nobody sees, what’s considered garbage.

The truth is that for a long time in my work confettï’s no longer confettï, but rather a world.

My final piece for the master’s degree consisted of three very long plastic strips on which I arranged confettï of three distinct origins (made in China, bought in San Francisco; made in Mexico, bought in Los Angeles; made in Mexico, bought in Mexico). Each strip contains infinite hours of work. I stuck them to the wall in a halted, static, very boring drop. I classified the party.

Dear Carolina,

I’ll allow myself to speculate that you have a history of confrontations that embrace bureaucratic absurdity, like a Kafkaesque figure but less depressed and more diligent; you pose situations that result in a kind of administrative situationist dérive. I imagine you as a child writing to the contact on cereal boxes in order to advocate for another type of prize. Have you ever received an answer? I think of your project for the FONCA [the National Fund for Culture and Arts] between 2018 and 2019, in which you launched an investigation from various fronts, including a correspondence with the Mexico City government, in order to locate the kilometer zero. For our readers, I’ll say briefly that “kilometer zero” is a singular point from which the distances of a city or a country are measured.

Dear Sofía,

Yes, this is precisely my stance before the world: to participate actively. The matter of politics has always been central for me, above all exploring its limits and its formats (in the minuscule, in the poetic, in the ephemeral). At some point I became obsessed with the thicknesses of lines on maps, with the way that, when represented to scale, they seemed to have no area. Which would be a serious territorial problem on a 1:1 scale.

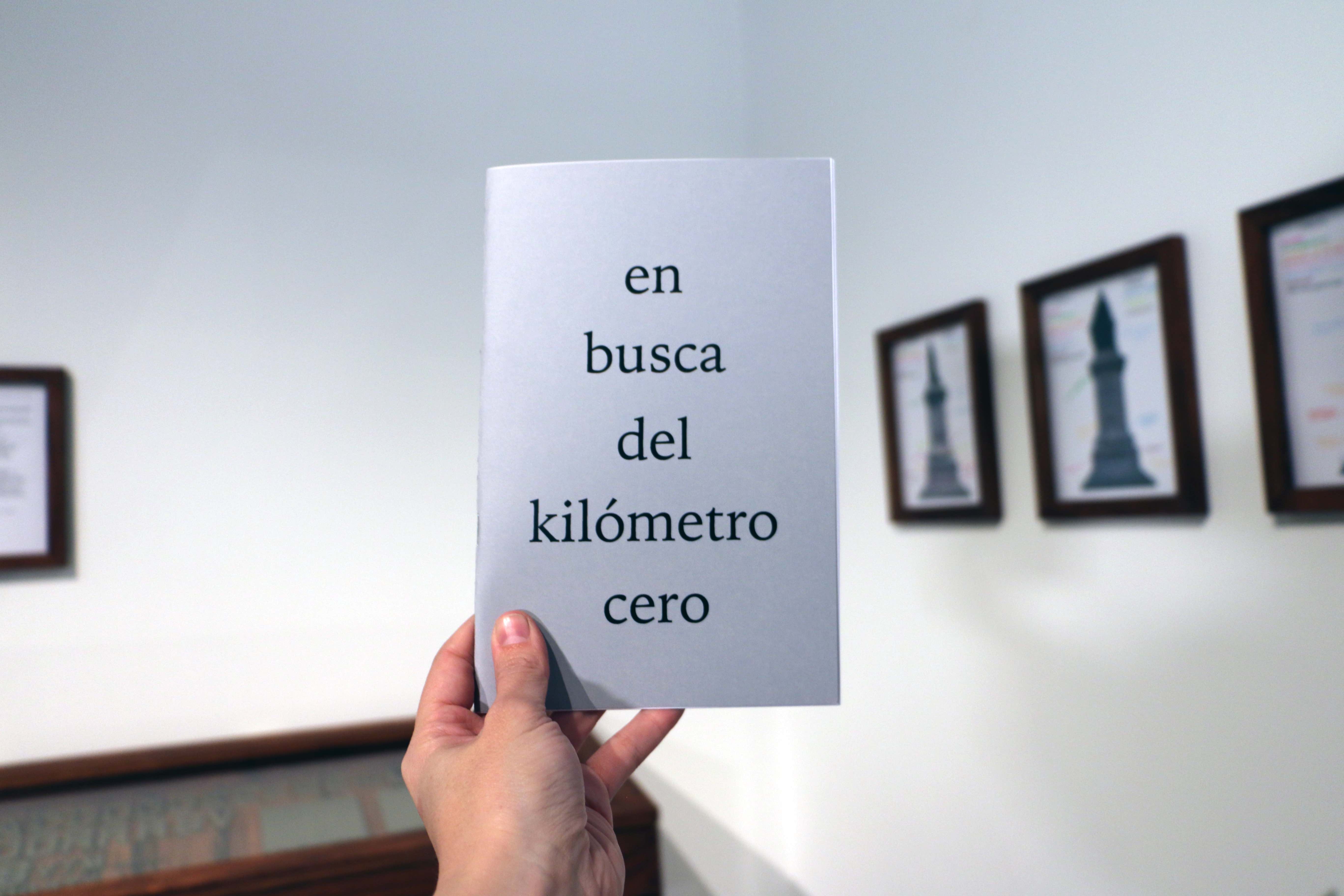

The premise of the project that I carried out with the FONCA grant began with the search for kilometer zero in Mexico. The title of the piece is Principio de incertidumbre [“Uncertainty Principle”]; I stole the term from quantum physics: you can’t want to know both the speed and the position of a particle at the same time; if you know one you have to accept that you give up knowing the other. One truth can coexist with another truth. This has been the search method I’ve used for the last 8 years. Today I can declare with total authority that Mexico’s kilometer zero doesn’t exist. Mexico has no center. Mexico has no navel. In any case, it has multiple centers.

The idea was to look for it everywhere, to listen to all the stories, to accept all the truths as simultaneously certain (even if they contradict each other). The project’s almost a mythology resulting from foundational myths of different kinds: kilometer zero is the Mariana Door of the National Palace or the central door of the National Palace or the flagpole of the Zócalo or the corner of Argentina and Guatemala Streets or the Plaza del Aguilita or it’s hidden under the Metropolitan Cathedral or it’s in a secret basement on 72 Argentina Street or on the second floor of the National Palace, in front of the office of the Secretary of the Treasury, or on the Monumento Hipsográfico (which was moved from its original position, from one side of the Cathedral to another). Or it’s not…in short, it’s not.

It’s a project of civil disobedience that seeks to question the limits of citizenship, the force of power to change history, to construct history, the possibility of the minuscule for shaking the entire system of values, truths, and authorities, even from its abstraction and its eventual nonexistence.

I’ll leave it here but not before saying that perhaps all this was beckoning when at age 10 I spoke on the phone with Clemente Jacques in order to correct a grammatical error on a dressing label.

Dear Carolina,

I’ve never thought about the thickness of the lines! How wonderful! Can you imagine being able to declare those territories as a kind of no-man’s land? Or as a space for landscaping that hides one country from another? Like in the wealthy suburbs that require “x” meters of trees between one house and another. Thinking about borders—how we measure them, their mythologies, and their shape—takes on another meaning in these moments of confinement. As you say, a truth can coexist with another truth, and in the pandemic borders are more present and more liquid than ever.

I think about the trip you took to the Kamias Triennial in Manila, Philippines, in February 2020: February! I want to read about how it went, what you presented, and how your body’s movement is manifesting itself in your work, in your ideas. You went from tracing lines (I think of the lines traced by airplanes on a world map), to your becoming one of the points that follow you (a blue point, fixed and quietly pulsating, in the Google Maps app on your cell phone).

Dear Sofía,

I could say that my work is divided in two. On the one hand, I associate color with everything I told you about confettï, streamers, and their derivatives; on the other hand, I think of the part of my work that’s black and white, and it’s here that I usually locate my fascination with maps. Speaking of lines and borders, I’ve done many projects in this regard. I’m very interested in the way that a line occupies space: if it’s on a wall it becomes a landscape; if it’s on the floor it becomes a border, it creates space, it divides, it forces one to decide to cross it.

Recently there have been projects in which colors and black and white are mixed, especially at the exhibition in Manila.

The project implied at all times a very intense consciousness of maps, in which going far, going around the world, and being a blue point on a map that goes around the world, became the center of my reflection. The pieces that I produced for that exhibition started out from a reflection on language, materials, and their circulation. All of them came about from a story my grandmother told me: when she visited the Philippines she went to the market and they offered her “Mexican mangoes” and she said, “But these are Manila mangoes!”

This story always fascinated me because it made me imagine interstitial mangoes, which grew in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, without identity. With this story in mind, I produced a series of pieces that play with language, above all with those objects that we call “from Manila.” I made some papier-mâché pieces: Manila mangoes with Manila paper pulp. I also made a series of Manila shawls belonging to post-post-post history, consumerism, capitalism… I was intrigued by those silk shawls that were embroidered in China, then traveled by ship via the Philippines to Acapulco, then crossed Mexico and finally sailed to Spain, in order to become part of the identity of Seville. In this way I made my version of these mythical shawls, but with plastic tablecloths made in China, China paper fruits made in Puebla, fluorescent pink threads made in China, bought in New York, and a cotton blanket made in Mexico.

I returned from the trip at the end of February and very soon the pandemic began. I felt like I was coming back from the future and it seems like I still haven’t fully processed this fantastic experience. It was a sum of distances and encounters, in which I’m still lost.

I think I would close our conversation with precisely this idea: the way we’re always in a search within our own work, like a territory, always on the threshold, from the threshold. That space that, once we understand it and feel that it’s dominated, we strive to complicate again. Thus is my work, something that, as soon as I begin to understand it, devours me.

A big hug,

C

Dear Carolina,

I remember that the last time we talked like this was next to a pool in Veracruz. Thank you for this conversation.

xx

sofía

sofiaortiz.work/ (Instagram @sofia_ortiz_s)

carolinamagisweinberg.com/ (Instagram @caromagis)

Translated to English by Byron Davies

Published on September 17 2020