Review

A Faun at Morán Morán: On the Exhibition Mapplethorpe: Escultura

by Mariel Vela

Reading time

6 min

Inside the gallery Morán Morán, on its impeccably white walls, there are rows of photographs arranged with precise distances between each other. All are framed in the same way, homogenizing the formats. The orchid arranged on a surface with its languid petals and legs spread towards the camera on a delicately wrinkled sheet. The floor’s gray marble is shiveringly cold: as though I could touch it with my eyes. I realize that there are certain exhibitions in which there exists an echo of bondage. With its materials and temperatures, the space ends up disciplining you until you reach contemplative immobility. A temporary suspension that contains pleasure, commands it, trains it.

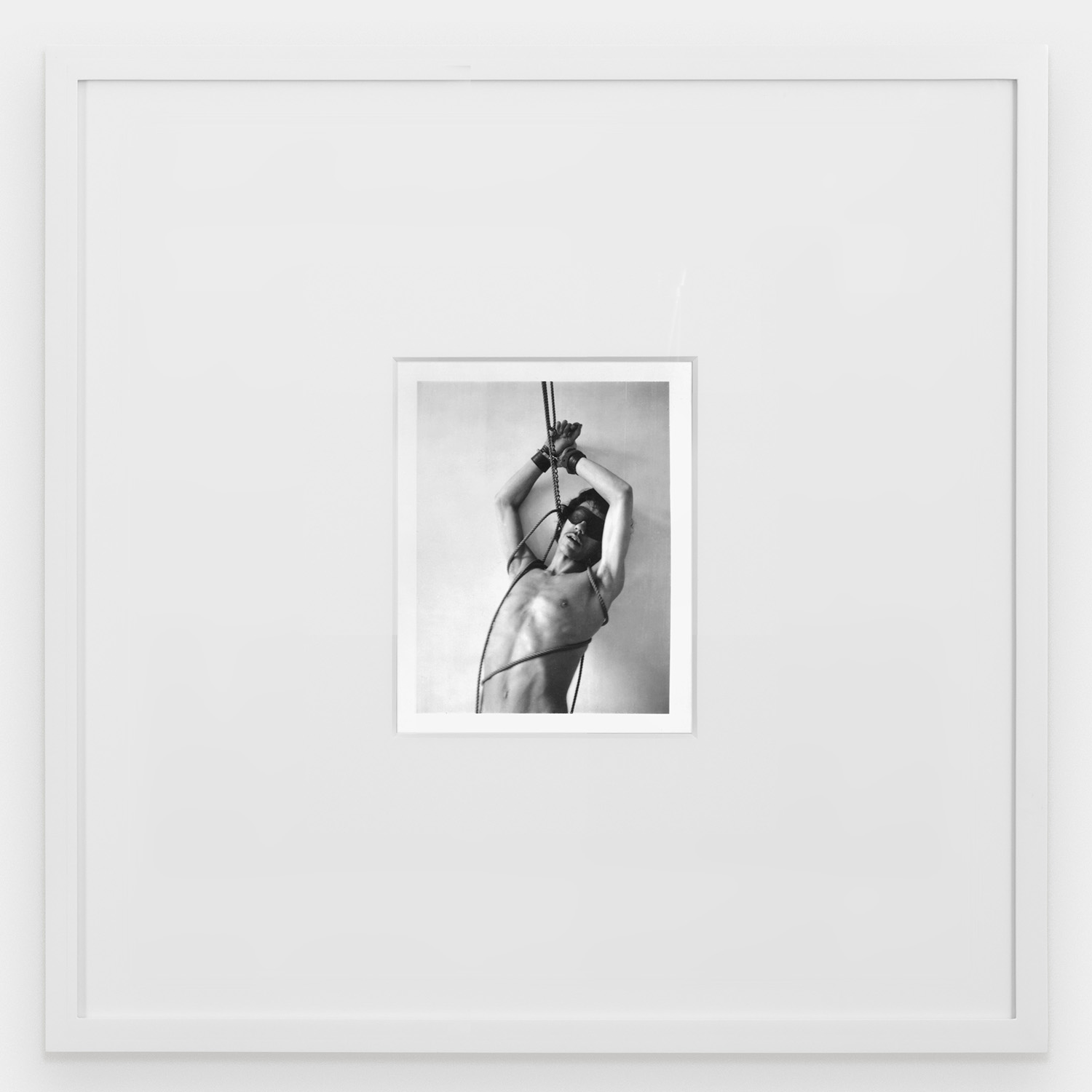

Mapplethorpe: Escultura is an exhibition curated by Tobias Ostrander that, through 36 photographs, explores the artist’s career-long fascination with the sculptural aspects of bodies and objects. The six black-and-white polaroids date from the early 1970s and constitute the format in which self-portraits tend to appear, interspersed with images of classical sculptures in parks and public squares. The series of silver gelatin prints began in 1978 and ended in 1988, covering the decade in which Mapplethorpe reached the apex of his celebrity and artistic recognition. There are flowers, leather harnesses, chains, portraits, and sculptures in marble and bronze that refer to one of Mapplethorpe’s most important retrospectives, The Perfect Moment, organized by Janet Kardon at Philadelphia’s Institute of Contemporary Art. Inaugurated in 1988, the explicit content of its images generated inquisition-like denunciations from groups such as the American Family Association. The Perfect Moment took place months before Mapplethorpe died of complications from HIV.

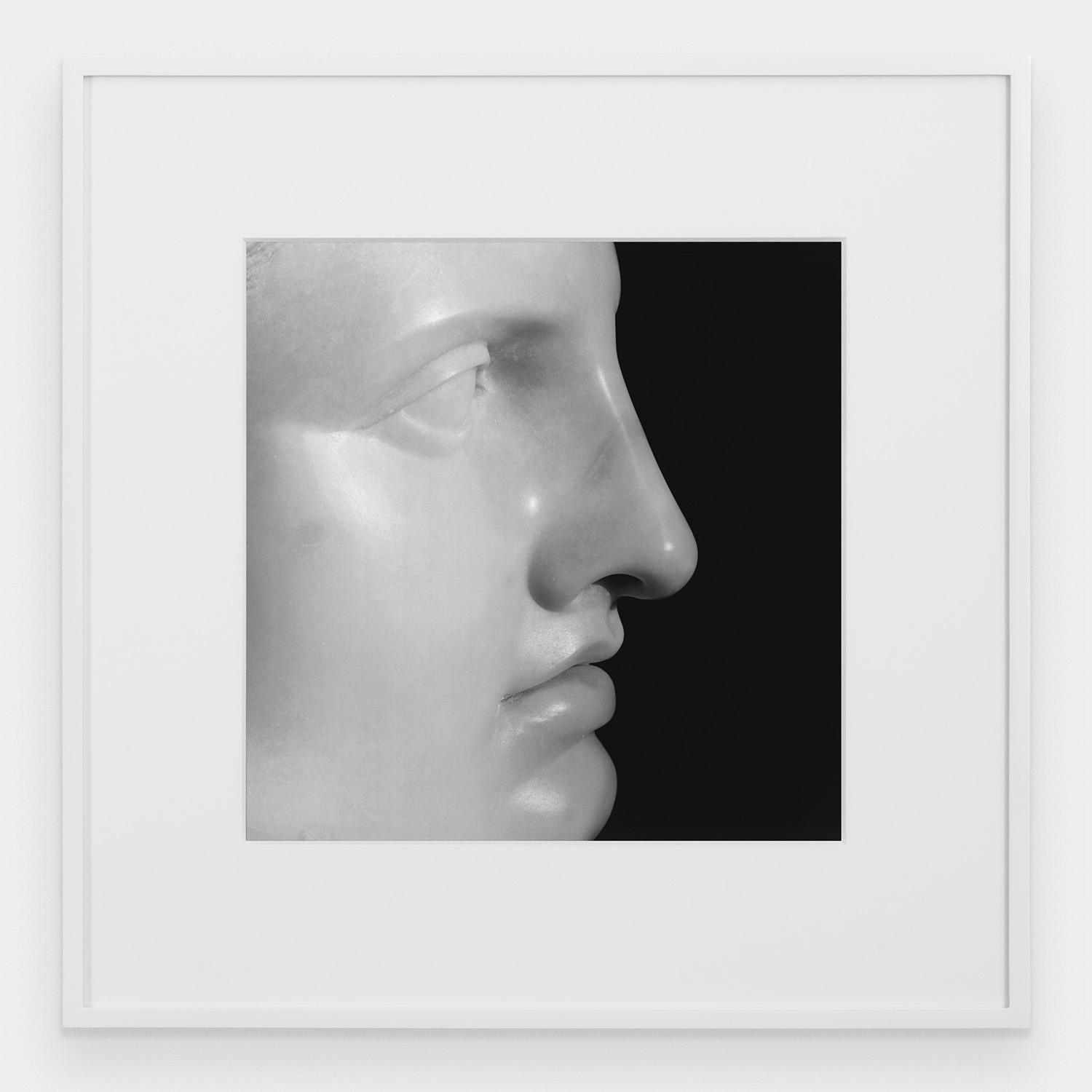

Apollo (1988) is carved again from the dark background against which he shows us his profile and looks out somewhere, that place where all classical sculptures look with their ghostly eyes. The contrasts generated by black-and-white photography present a recognizable composition within the genealogy of art history. For a Renaissance sensibility like Mapplethorpe’s, there is no division between form and content, like that proposed by 1970s conceptual art in the U.S. The drapes hanging in some backgrounds, as well as the stone bases on which photographic subjects are placed, augment the inseparability between flower bulbs and testicles, skin and marble. Everything becomes an exercise in proportions: the human eye judges and receives beauty in its correct execution.

There’s an oil painting depicting Lucrezia Borgia, carried out between 1519 and 1530. She was born on April 18, 1480 in the midst of the Italian Renaissance, and was married to Alfonso d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, forming one of the period’s most important marriages for artistic patronage. At the bottom of the painting, written in gilded Latin, is the inscription: CLARIOR HOC PVLCRO REGNANS IN CORPORE VIRTVS (“Clearer than beauty is the virtue that reigns in this virtuous body”). For many years this image was believed to be of a nameless young man. On the reverse side of the portrait of Ginevra de’Benci, painted between 1474 and 1478 by Leonardo Da Vinci, one finds among laurel branches and palm leaves the sentence, also in Latin: VIRTVTEM FORMA DECORAT (“Beauty adorns virtue”). This kind of textual accompaniment is characteristic of many Renaissance paintings, largely owing to the then-renewed interest in literary works of classical antiquity like Virgil’s Aeneid (1st Century BC), commissioned by the emperor Augustus with the aim of establishing Roman virtues or values to which citizens could aspire, such as salubritas, humanitas, and veritas. A virtuous body is one that is healthy, human, and true.

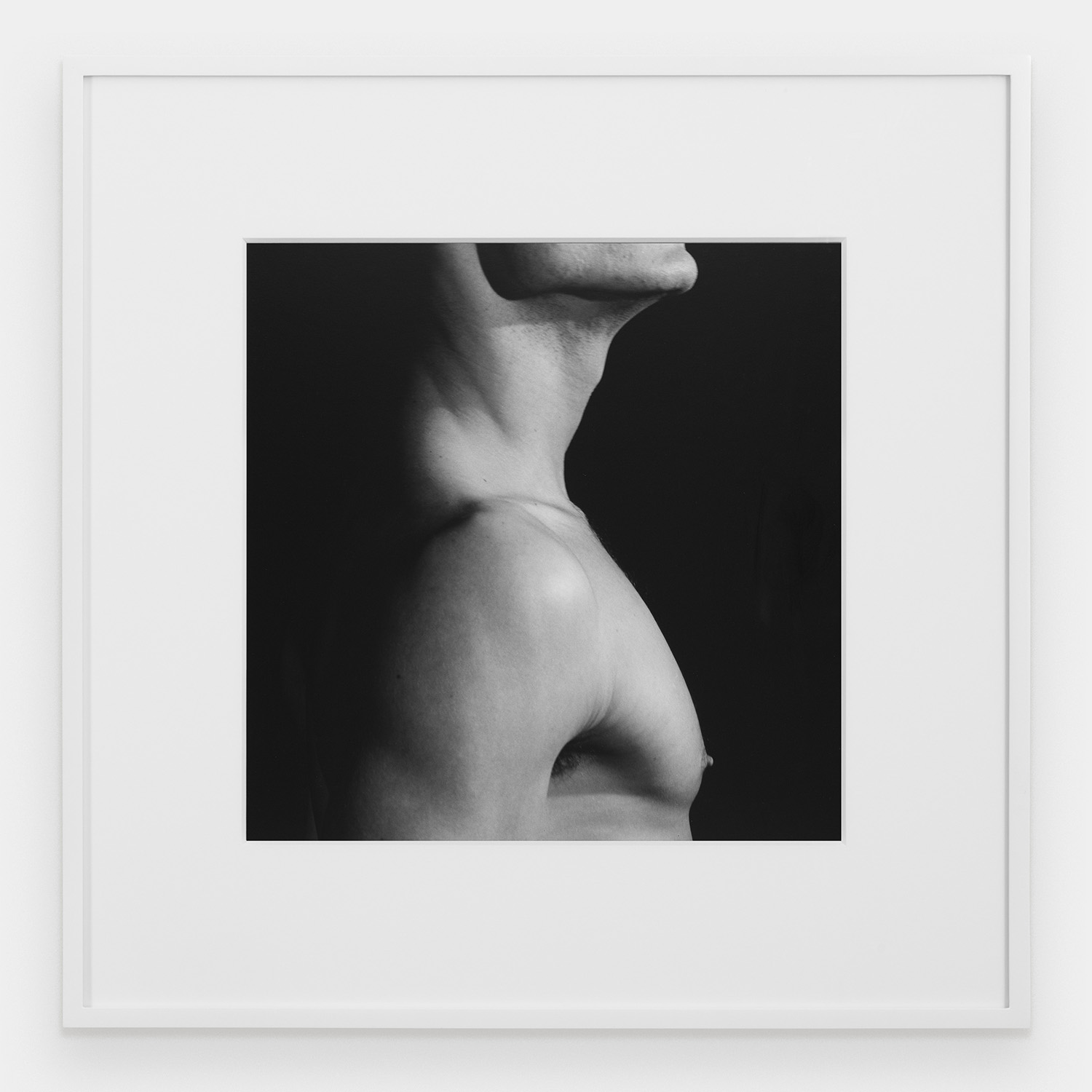

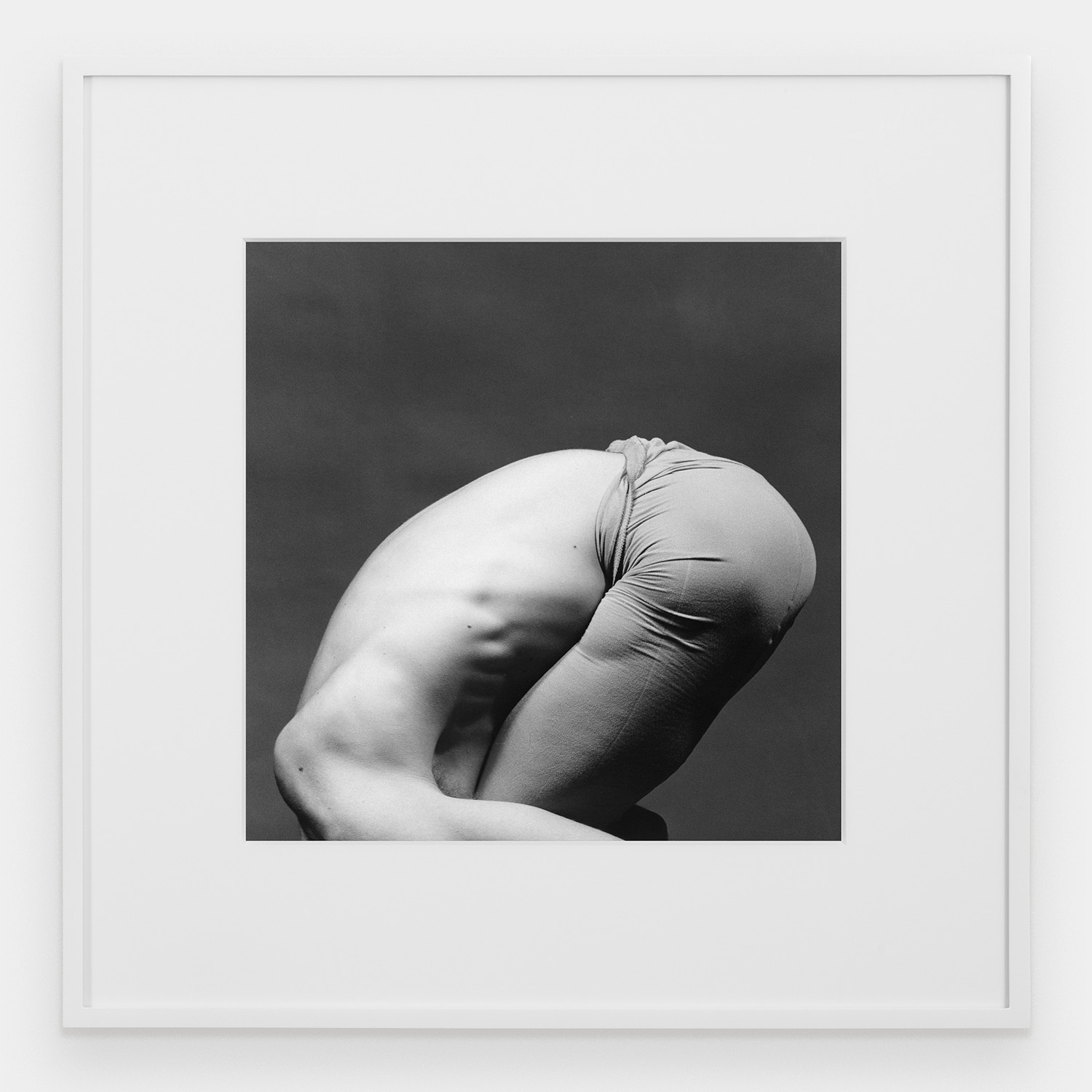

“Virtue” comes from the Latin word virtutem, which means “power” and is related to the root vir, meaning “man.” Roman humanism and the Christian values derived from it are the bases upon which a human ideal was configured as masculine. The way that Robert Mapplethorpe would stand on a tendon and use the techniques of silver printmaking in order to accentuate muscular recesses is a continuation of these ideas, even if they are in tension with the context of countercultural New York, in which the purity that constituted a loving relationship between two men in ancient times was now related to perversion. It is also significant how many of the photographs only show certain parts, perhaps as a reference to Greek sculptures and their states of ruin, displaying incomplete bodies: the legs of Milton Moore (1981), the torso of the dancer Peter Reed (1980) bending over and embracing himself, as well as the chiseled jaw of Dennis (1978). At the same time that they represent an idealized masculinity, they also challenge what constitutes a virtuous body, a healthy body, or a beautiful body.

The Young Men's Christian Association (Y.M.C.A.) was founded in 1844 by George Williams as a space in which young men could develop healthy minds, bodies, and spirits, based on Christian principles. I think of the sculpture of Mussolini photographed in 1988 and of how dangerous the erotic dimensions of worshiping youth can be, both in fascist imaginaries and in youth organizations. During the seventies the Y.M.C.A. had the hint of being a place for cruising or for seeking sexual encounters. When they were asked about their political stance, members of the Village People (the band that immortalized the hit “Y.M.C.A.,” as well as “Macho Man,” in 1978), responded: “Whatever. We’re not Joan Baez.” I don’t want to over-politicize this exhibition’s photographs of BDSM sex acts and leather culture; rather, I prefer to see them as reflections of the masculine utopias that the artist found in bars like the Mine Shaft in New York, one of those places in which prestige was largely determined by who was refused entry, including Rudolf Nureyev.

The Mine Shaft dress code

as adopted by the club on October 1, 1976

is to be followed during the year 1978.

The Board of Directors

Approved dress includes the following:

Cycle leather & Western gear, levis

Jocks, action ready wear, uniforms,

T shirts, plaid shirts, just plain shirts,

Club overlays, patches, & sweat.

There is a self-portrait of Robert Mapplethorpe dressed as a faun (1985). He looks at the camera and at me, reminding me that I can’t take all of this so seriously. The leather counterculture emerged after World War II, with men renouncing the values and heteronormative structures of the nuclear family: a flight from the era’s virtue and good citizenship. I keep thinking, not so much about ideals of Renaissance beauty, but rather about the friendship of Niso and Eurylus, who, had they been born in New York in the postwar period, would surely have escaped on a motorcycle or danced all night dressed in leather.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

The exhibition Mapplethorpe: Escultura is on view at Morán Morán, Mexico City through August 18, 2021.

Cover picture: Robert Mapplethorpe. Self-Portrait, 1985. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation.

Published on Aug 7 2021