Review

Todos los viernes pasamos por aquí, an exhibition by Julián Madero Islas

by Eric Valencia

At Ladrón galería

Reading time

7 min

And what if painting is a material hallucination, placed before our eyes in order to participate in it? This question arises for me as I examine the works of Todos los viernes pasamos por aquí [“Every Friday We Pass Through Here”] by the artist Julián Madero Islas, curated by Christian Camacho and currently being presented at LADRÓN galería.

Given their explicit violence, it’s difficult to access these scenes without some stupor. In talking about these works and about the exhibition, I would prefer to make my own feeling evident in the form of a kind of suspicion, and to try making that the basis for an interpretative method. It starts from the premise of approaching the work without believing in ghosts. This would reveal a series of highly complex pictorial operations that take place in Madero’s work. The proposal is in no way to overlook the violence, but rather to see it as a resource for the image. Is it justified? We’ll see.

The Works

Nastagio reflects on the scene unfolding before his eyes: a woman’s soul is punished for responding with contempt to a man’s overtures of love. Upon seeing himself wrapped up in a similar situation, that of being despised by the woman he “loves,” he decides to use the scene to alter the outcome of his own story. He organizes a banquet in the forest in which the woman he is courting will meet alien and ghostly tragedy. In this way, the woman will witness the future punishment that her soul will suffer if she does not agree to marry him.

This is, in broad strokes, the eighth story of the fifth day recounted in The Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio (1351-53), entitled “Hell for Cruel Lovers,” and which served as the theme of a series of four paintings made by Sandro Botticelli as a wedding gift for Giannozzo Pucci and Lucrecia Bini in 1483 and which, in turn, Julián Madero has reinterpreted for this exhibition. The artist’s most obvious change is the inversion of the genders of the ghosts: man for woman and woman for man.

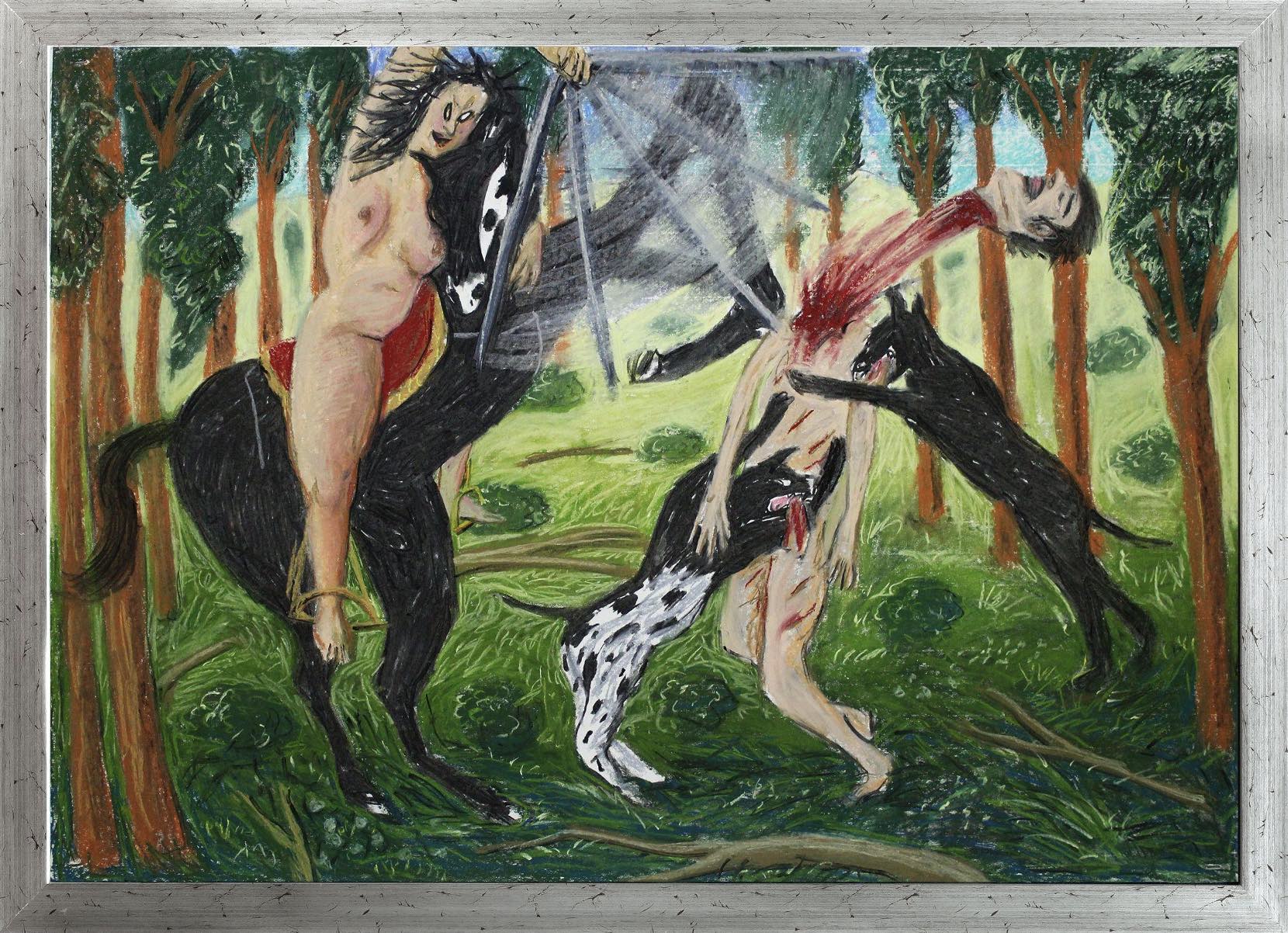

Todos los viernes… greets the visitor with the painting Caballo Blanco, representing the moment when the man’s ghost is disemboweled by the woman’s ghost, both of them naked. This scene corresponds to the second painting of the triptych Historia de Nastagio de los Onesti [“The Story of Nastagio degli Onesti”] by Madero as well as the second one in the series of the same name by Botticelli. The details of the death of the male character are repeated with different variations (now by the sword, now by dogs) in the works S/T 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and in Espada. This is the image that summons us.

The Missing Images

We know from Bocaccio the details of the story that we see unfolded in the paintings. The contempt shown for Nastagio by the woman—which gives rise to the story behind the works—and Nastagio’s wedding with the woman: which corresponds to the fourth panel in the Botticelli polyptych, one that Madero has decided not to paint.

Pascal Quignard (2015) writes about the relevance of these missing images for the history of a certain kind of painting: “An image is missing at the origin. None of us were able to attend the sexual scene of which we are the result. [...] An image is missing at the end. None of us will attend, living, our own death.” In order for us to get closer to Madero’s proposal, this thesis is of great pertinence: painting is the tension between these two moments. “Medea meditates: in the ancient world meditation is imagined as a debate between voices, taking place inside the body.”

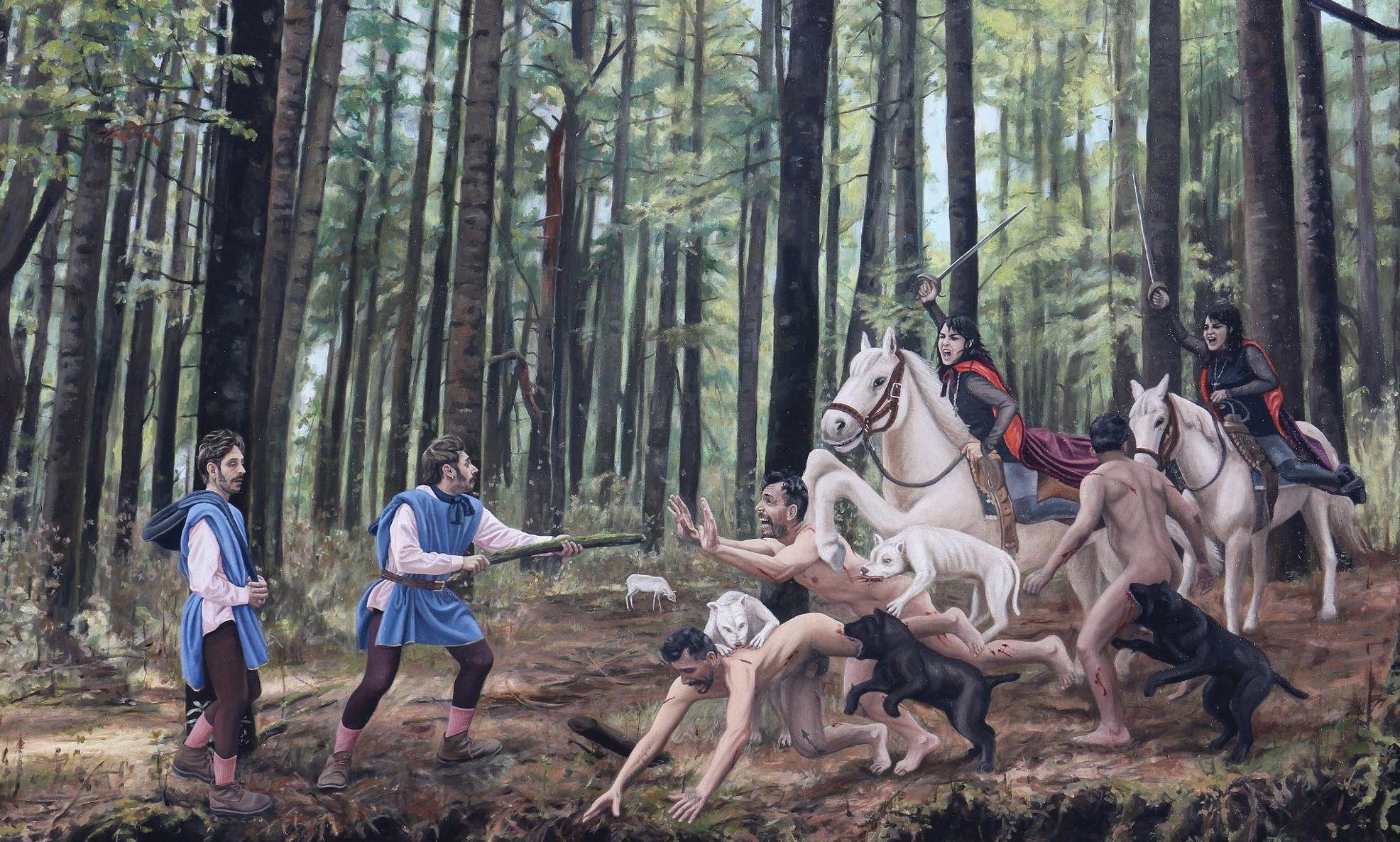

Thus, we see the triptych Historia de Nastagio de los Onesti as the development of this tension, of this meditation, of that debate taking place inside Nastagio. The first module corresponds to the moment in which he witnesses, in the forest, in solitude, the bloody encounter between ghosts. He wants to intervene but is soon convinced that he can do nothing against divine designs. Let’s recall that we don’t believe in ghosts, at least not in the typical sense referred to by Bocaccio’s story: in supposed spirits or souls that manifest themselves before us. We don’t believe in ghosts/phantasms. This being the case, what do we see? What, then, does Nastagio observe? In The Logic of Phantasy (1966-67), Lacan defines it as what sustains, in the subject’s unconscious, their desire, and determines their way of enjoying. The dream and the hallucination are two ways in which the ghost/phantasm returns (from) the repressed. We see Nastagio’s hallucination, his own “ghosts.”

The second module of this triptych is the scene in which the naked man is murdered by the woman on horseback. We see Nastagio horrified, trying to flee but still attentive to the scene. Following Quignard, “a deep desire not to see the Real allows one to see the image.” Painting is the consolidated image, put on view. By whom? By Nastagio himself: it’s his work. There is no one with him to take stock of the veracity of his hallucinations. He believes them to be real: this bloody spectacle is the staging of his hallucination turned image, turned painting.

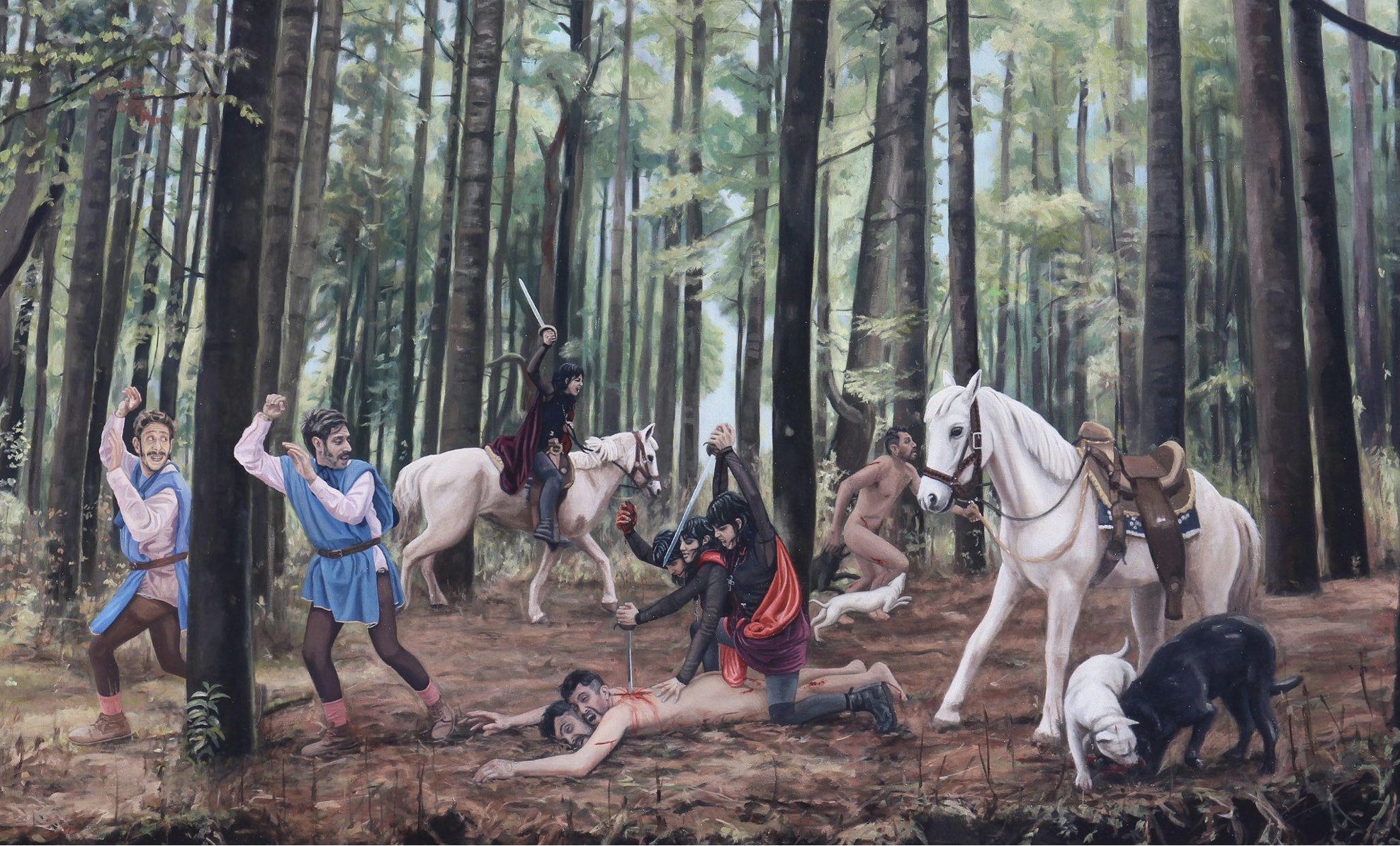

In this third module we see how this image is made visible to everyone. Nastagio has organized a meal and invited the woman who despises him, as well as all the ladies related to her, to witness the staging of their own delusions. In this painting we witness a mise en abyme, a placement in the abyss. If we already suspected it in the triptych’s second work, this module confirms it: current, living people that we can recognize are witnessing the scene. Madero himself appears there. I hear his voice upon visiting the exhibition: it is reflected in the work and in its reflection it includes me, it includes us, as participants in and witnesses to this madness concocted by Nastagio. We don’t believe in ghosts, though what we see, what Nastagio makes us see in the whole triptych, in his own desire in painting. And it is a painting that, placed in the abyss, challenges us.

Botticelli’s fourth module, missing in Madero’s triptych, is that of Nastagio’s wedding with the woman who previously had not reciprocated his overtures of love. In this scene, she has not only “converted her enmity into love” by agreeing to nuptials, as Bocaccio tells us, but also “the ladies of Ravenna in general were so frightened […] that they became much more tractable to men’s pleasures than they had ever been in the past.* ” We might interpret the absence of this module as an open ending, as a possibility of reflection on these repeated instances of violence. Shall we, who have been invited to the banquet, give in to this extravagant form of coercion, of coercing? The missing image is happening right now, right here.

Todos los viernes pasamos por aquí can be visited at LADRÓN galería until February 2022.

*: Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron, trans. John Payne (New York: Penguin,

Published on December 18 2021