Essay

To Action the Tragedy: Jean-Charles Hue

by Fabiola Talavera

Tijuana Tales at Lulu

Reading time

6 min

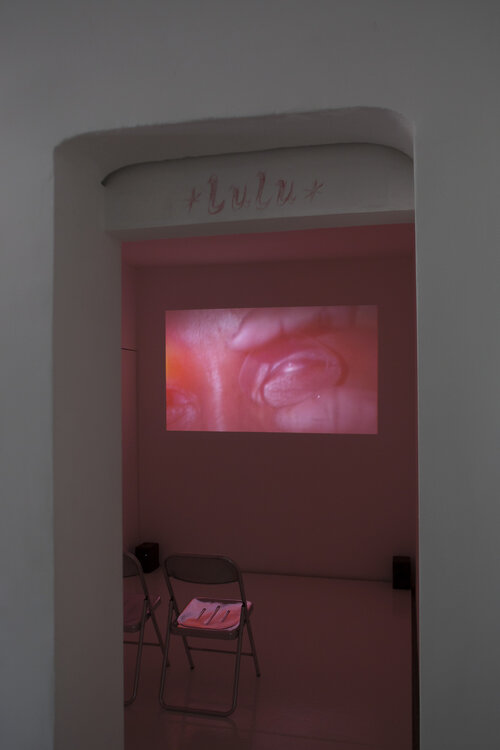

Lulu presents its most recent exhibition: Tijuana Tales (2017), a short film by the French filmmaker Jean-Charles Hue. In the front gallery, a series of stills show the film’s most representative moments. In the back, the short film of just over ten minutes is projected. Hue’s film is not only striking for the situation it portrays, but also for its form, which refers to an awareness of the medium itself. Having filmed it in 16mm, Hue knows the possibilities afforded by a portable camera to be in the center of the action without being seen, and, likewise, of the materiality added by celluloid, that with its flashes of light and corrosion provides a dimension of reverie, reminiscent of another era, to the urban landscape it portrays.

With an extensive film career, Jean-Charles Hue often puts unusual subjects in front of his lens. Oscillating between documentary and fiction, his early films portray Roma communities on the outskirts of Paris, creating filmic narratives within those contexts. For more than thirteen years, Hue has been roaming on Mexican grounds. The border city of Tijuana has become, over the years, the focus of his attention. There, Hue has shot multiple films, such as Tijuana Jarretelle le Diable (2011), Agua Caliente (2013), Crystal Bullet (2015), Tijuana Tales (2017), and Topo y Wera (2011-2018).

Hue is about to release his next film, Tijuana Bible (2020), a feature starring the English actor Paul Anderson and the Mexican actors Adriana Paz and Noé Hernández. The film shows the story of an American war veteran who, by getting involved with a Tijuana woman, draws the attention of the drug traffickers who control the city. Before producing this higher-budget film, Hue spent time living first-hand among the criminal underworld of Tijuana’s Zona Norte and getting involved with its occupants. His films, in an abstract sense, draw elements from the filmmaker’s experience in that city.

Right on the border with the United States, Tijuana’s Zona Norte, replete with strip clubs, brothels and bars, is a hotbed of criminal activities, drug trafficking and sex tourism, largely fueled by its neighbors to the North. In a blurry zone of tolerance, women of all ages wait day and night “paraditas” (standing) for a client to solicit their services. These are the protagonists of Tijuana Tales: women with addictions, with distant or missing children, working the streets.

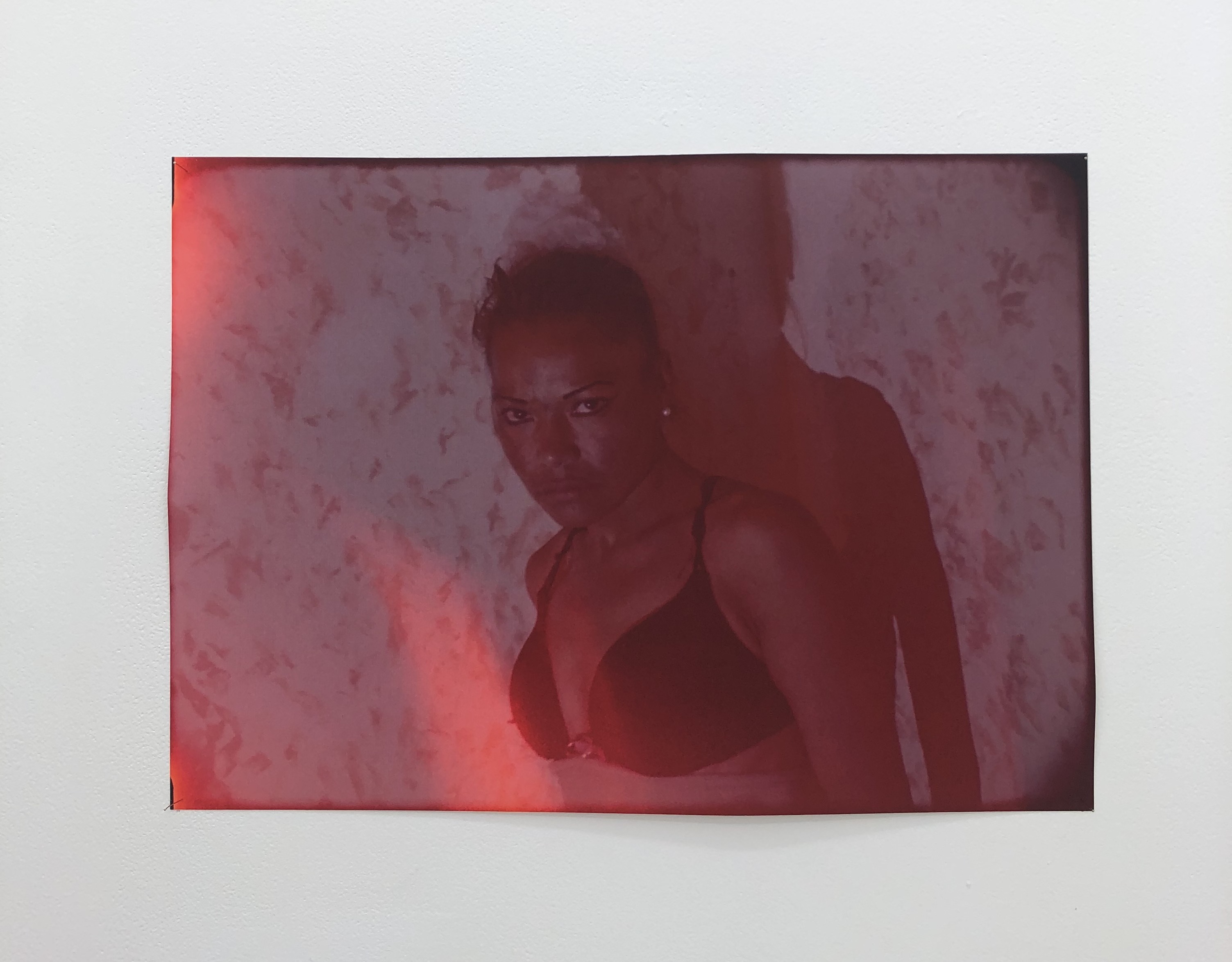

Although Tijuana Tales largely partakes of elements of documentary in its portrayal of everyday life on the streets and the people of this neighborhood, Hue sets in motion one of the director’s most fundamental tasks: he actions his subjects. Establishing different relationships between people and the world around them, Hue directs the protagonists of his short film to act in scenes symbolic of their inner worlds. Roxana, a woman addicted to crystal meth, paints a red cross on the walls with her hands; the omnipresent demon that stalks her is embodied in the figure of a man covered with tattoos, who sees everything from behind her. Ana, lying on a bed full of objects, in all innocence plays with a star bearing plastic diamonds; she’s queen of her own planet. For a moment, these stagings suspend them from their realities.

It’s believed that the origins of acting date back to the Dionysian rituals of Ancient Greece. Through the dithyramb, a choral poem dedicated to Dionysus, a cleric would lead the religious ceremony by incarnating the aforementioned god. Bringing that divine figure to earth, so that listeners could see and hear mythical stories, caused the audience to ratify their belief in him and to abandon themselves to ethylic and carnal pleasures. Little by little the audience’s participation would diminish and the actor’s voice would gain more prominence. In these ancient ceremonies, the human tendency for the mimesis of life’s acts gave way to Greek theater in its classical period, and in particular, to the genre of tragedy.[1]

Tragedy in Ancient Greece was understood as a composition that staged fearsome and compassion-worthy events, unfortunate acts of heroes that cathartically purged their spectators by giving them the possibility of experiencing such emotions without having to live them.*2 The modern notion of this genre can be attributed to Arthur Schopenhauer; this author referred to tragedy as the representative condition of the terrible aspects of life, of ineffable pain, of the misery of humanity, of the triumph of perversion, of the disdainful domination of chance and the hopeless fall of the just and innocent. But above all, tragedy is in essence for Schopenhauer that in which the protagonist does not take into account his particular sins, but rather the original sin: the guilt of existence itself.*3 Tragedy has evolved in contemporary cinema in order to create victims of great misfortunes. In Oldboy (Park Chan-wook, 2003) or Dancer in the Dark (Lars von Trier, 2000), the tragic characters are those who, no matter how hard they try, cannot avoid their fatal destiny.

Tijuana Tales opens and closes with an image: a rose in a crystal ball, the moment of its freshness and beauty frozen in time, a metaphor that encircles the fleeting vivacity of its characters. On other occasions, as in Topo y Wera (2011-2018), Hue follows his subjects of study for a long time, showing the decadence that addiction sometimes entails. That’s not the case with the film exhibited in the back gallery of Lulu. Tijuana Tales displays how tragedy can be much more heartbreaking through not being shown and rather only hinted in the storytelling.

The eyes, a recurring element in Hue’s work, are sometimes used as a symbol that anticipates a catastrophic reflection. Marlene, with a battered eye, shows off her collection of glass lenses that she claims bring her sight back; she says she saw herself die three times. Roxana describes her visions of the devil, and from the neck of the character who accompanies her in the room, hangs a pendant showing an open eye. The women of Tijuana Tales walk the fine line between life and death, where the promise of salvation in eternal life is more virtuous than the transitory blink of an eye that is mortal life. Under Hue’s gaze, the protagonists become spiritual guides who take our hand leading us down the spiral of hell: local legends of souls in pain telling tragic stories. But also, on several occasions, these women look at us directly in the eye, break the fourth wall, and remind us that not everything is an act.

[1] Aristotle, Poetics in The Complete Works of Aristotle (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), 1449 a 5-30.

[2] Ibid., 1149 b 20-30.

[3] Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation. Volume 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), pp. 280 – 281.

Published on August 23 2020