Essay

The Taste Buds in the Bags under Our Eyes: On the Work of Renard and the Writing-Drawing Spiral

by Christian Camacho

Reading time

8 min

Then, the signs, certain signs. The signs tell me things. And I would definitely be happy to make signs, if not because a sign is also a STOP sign.

Émergences- Résurgences, Henri Michaux

As they rise into the vision of my nights and I mull and digest their comings and goings, the family becomes a familiaris, internal accompaniments, no longer quite the literal people I engage with daily. Gradually the family moves from being the actual persons I must resist and contend with, to living ancestors, ghosts or shades, whose traits course within my psychic blood giving me support through their presence in my dreams. My family home shifts its ground from gē to chthōn.

The Dream and the Underworld, James Hillman

Although Renard's work in the city of Monterrey has been known for several years, I have in fact come to it thanks to various recent encounters: conversations and visits that should have taken place earlier, but that I am happy to take into account today. As it happens, the last thing I had access to was their writing, in the form of two publications edited by curator Virginie Kastel in 2019, and gifted by Renard themself a few months ago.

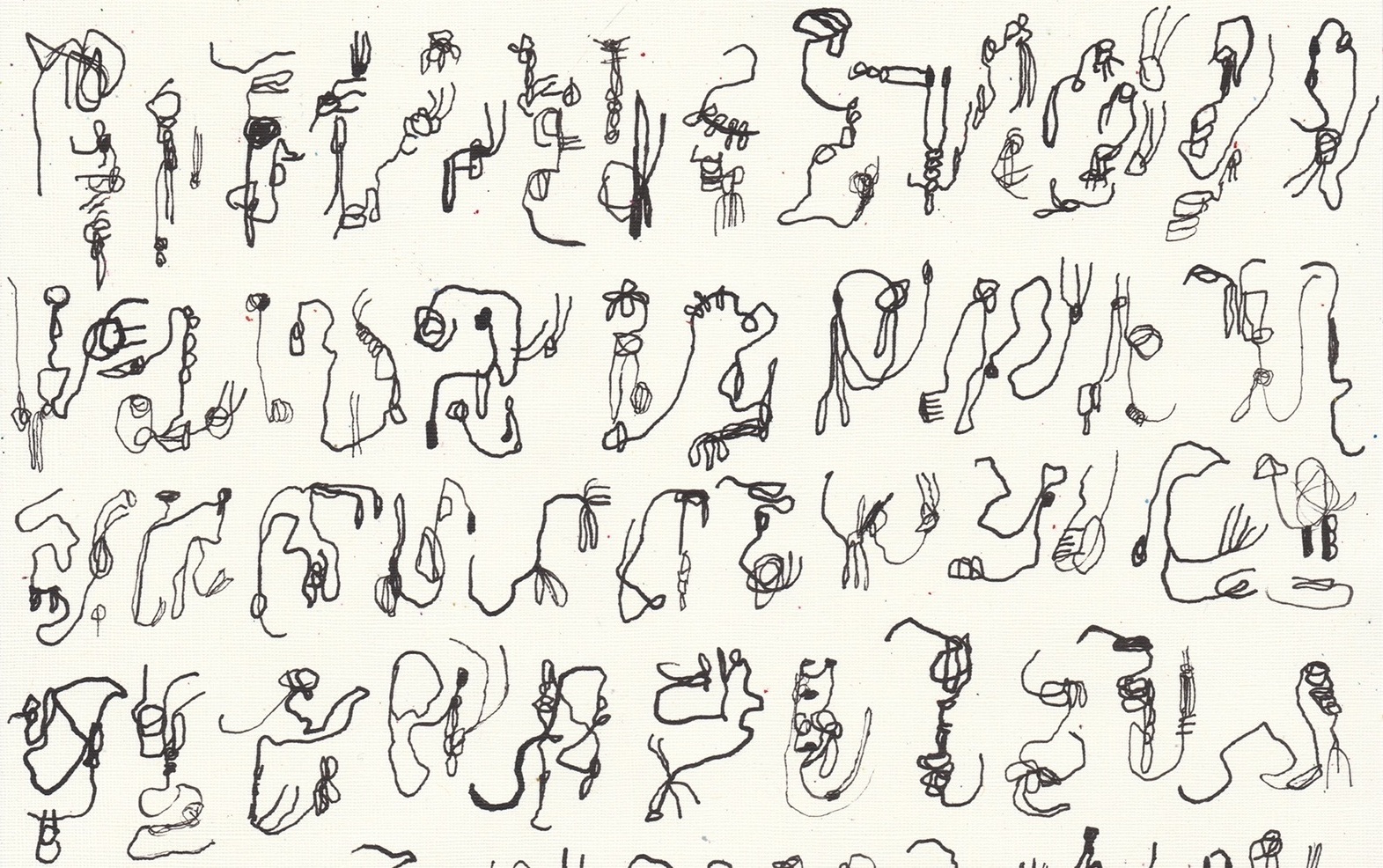

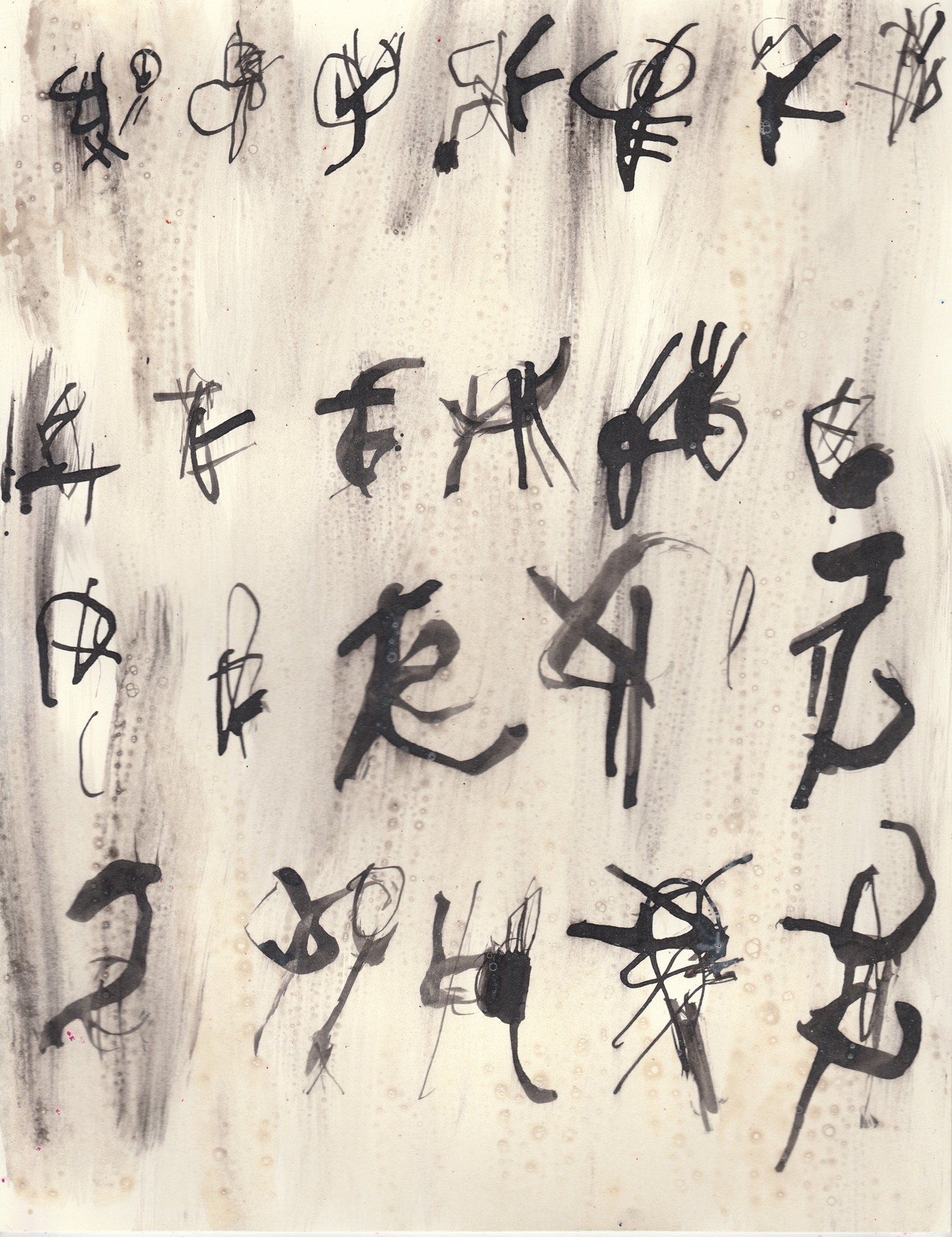

The overlapping of different ways through which Renard’s practice exists addresses me from an agency that is simultaneously instantaneous and schizoid, but also calculating. Undertaken in a sea of different gestures, it is perhaps the product of a prosperously anti-orthodox artistic training. The resulting burst of signs, feeding on the free particles of their experience in the theater and the strange expectations that exist between performers and audiences, at once prepares a site for performance, drawing, writing, and painting. I feel that this volatile mixture, which serves as fuel for the work, puts all these elements at constant risk of evaporation, but also mobilizes with sufficient discipline in order to push the whole a few centimeters into the unknown.

And speaking of volatile, I think “volatile” twice: on the one hand, the volatility of their handwriting, and, on the other, the ideas produced by the anxiety of being the very reader of this handwriting. I feel that their writing is propelled with wear. And that there is a certain type of drawing that likewise does this and that is present in the mind by demanding things from a support, as though every background and beginning were also that of a page. Something that, once traced, is capable of revealing things about us. There is a power in the pursuit of that revelation, as well as a paranoia in its eventual inevitability. A trait of “writing about ourselves” whose enlightened masochism tends towards the addictive as well as the unintelligible: we would never accept that it is unintelligible because it never is.

In this sense, the mind and its position in reference to the emergences and collapses of meaning in Renard’s activities is insistently described in the present tense.

This rapid pathway, flowing in lines whose metaphors Renard does not deem necessary—Subliminal and literal, I don’t see the difference*1—reminds me of one of Cy Twombly’s most famous teachings on drawing and thinking, which tells us that the act of the line is like a nervous system. It’s not described, it’s happening. The feeling is going on with the task. The line is the feeling, from a soft thing, a dreamy thing, to something hard, something arid, something lonely, something ending, something beginning. It’s like I’m experiencing something frightening, I’m experiencing the thing and I have to be at that state because I’m also going.*2

In our last conversation Renard told me about a line similar to song—both muscular and sonorous—which is of interest to them. Perhaps this announces their links to performance as a practice, though in reality I wish to attend more to the performative within their own collection of handwritings. If we look at Renard’s painting or drawing from a distance, there is a temptation to name the coordinates of this or that tradition as though it were their own. Qualities of expression, abstraction, or gesture. It is not necessary to dismiss these terms, but I feel that they in fact do little to introduce us to the tangle of needs to which their practice responds.

The French writer and artist Henri Michaux, whom Renard has also consulted with interest, employed the title Infinite Turbulence for a series of autobiographical texts and drawings accompanying his trips while using mescaline. What interests me most about these trips is not really the alteration of perception, but rather the kind of movement, in the first-person and in the present, in which only two things become essential: drawing and writing. At a certain point in describing these events, Michaux speaks of a moment whose color comes from blindness, but that begins to turn white: first a piece of chalk, then a type of diamond, and then sheets and flags that wave with such energy that they could be waved by the inhabitants of an entire nation. I have always wanted to think that this dizzying white in the midst of so many inevitabilities is the white of his pages.

Perhaps this is the reason why certain practices sometimes seem audacious to us, not only because of their connection with the free possibilities between the genetic and the generic, but also because they seem to bring into play a moment whose imagination is not intended to be immediately describable, or even compatible, for others.

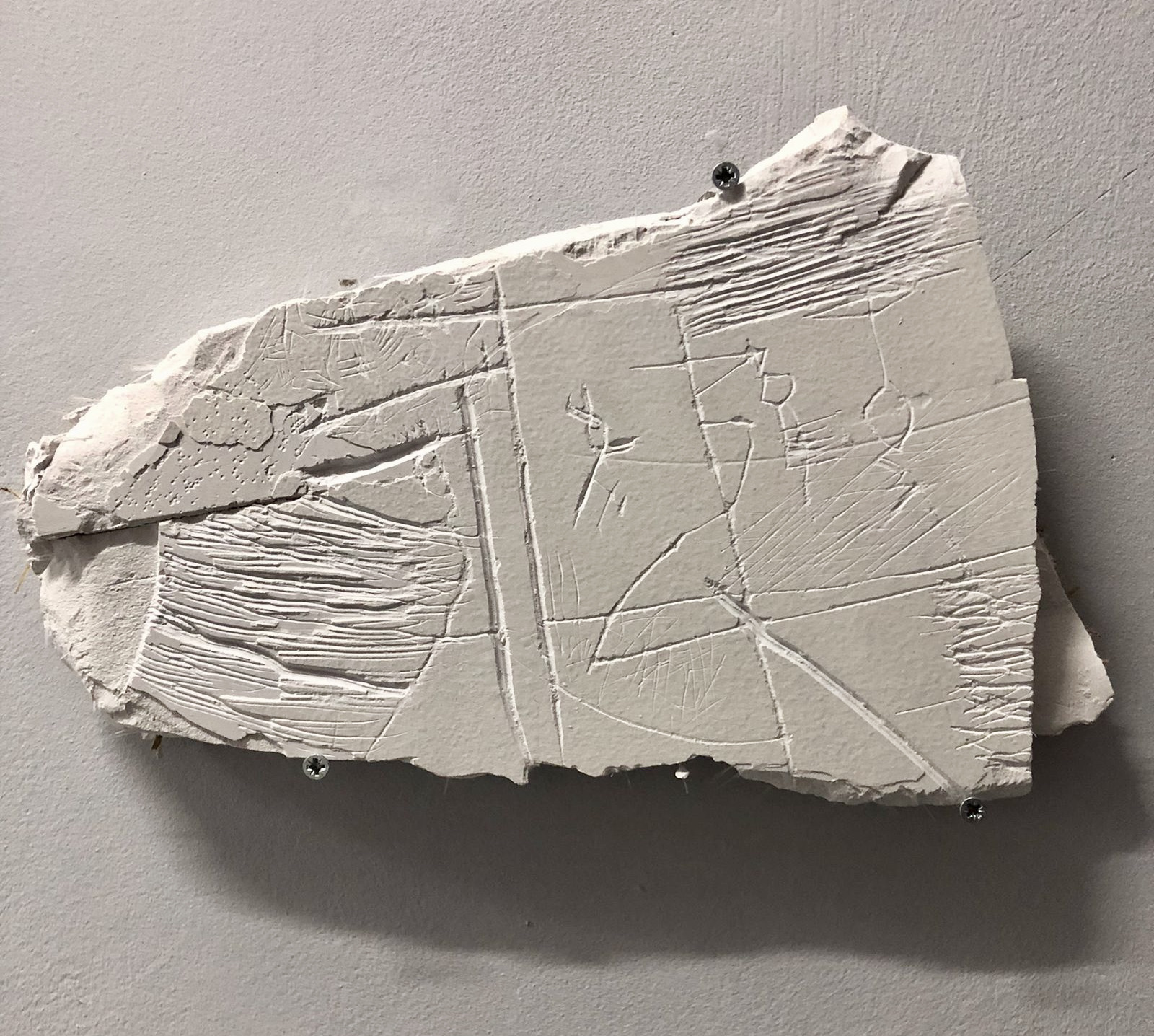

At this moment I can discuss another part of Renard’s work that I find valuable, and that has to do with their ability to move through such minimal self-sufficiencies as their relationships with the murmur and the economy of their supports. Michaux wrote that writing, in contrast with drawing, was never sufficiently impoverished; that language, an immense and necessarily inherited mansion, throws us all into ostentation.

I am not sure how we can negotiate with this judgment, but I believe that trying to do so makes our acts in this regard, however small, acts of tension and renunciation.

One of the publications by Renard that I mentioned at the beginning of this text is titled POS A DAR*3 and it covers, in broad strokes, the events of a holiday party like the one phonetically suggested by its title.[4] It is not clear what is taking place in this entire episode, though neither are we looking to know it in detail. Family members, numbers, desires, and indigestions seem to possess the same body, one that despite its best intentions, cannot stop. The stroll through this writing reminds me of the use of monologue in introspection, as well as of some instances of reverie and the desire to empower in waking life, neither more nor less consciously, the artistic implications of that mutilated ghostly crowd that we think we know while dreaming—it’s no longer a matter of saying “mom” or “dad” again, but of saying it to anyone.*5

This link to reverie is a powerful tool for the work and the language surrounding it, in which fragments of ideas and words circulate unopposed through the chthonic jelly of drawing folded into writing—the set of dead cells that is organized alphabetically.*6 This also heralds one of Renard’s interests in the pathways of language and the possibility that their compatibility is absolutely full. Participation in reverie, fragmentary as it is, cannot help but be significant. Thus, the sense of familiarity of communicative events in the dream underworld in fact fuels a boycott of the grounds on which daily work is perceived as rational. In this instance, Renard belongs to a long tradition, that of saboteurs.

I would like to close this text by becoming aware of the time I have been writing, in contrast with the time that perhaps you have been reading this and looking at these images. I thank Renard for this particular fragment, which perhaps serves as a conduit:

When something lasts longer than a dream, which is a maximum of forty-five minutes, I begin to doubt its legitimacy, economic value, and whether something is burning in the pan. It’s quite possible. But when something begins to last more than seven hours, it begins to take on a tasty juice that stimulates the taste buds in the bags under our eyes, and we squint little-by-little in order to get to tasting the acidity of things.*7

Translated to English by Byron Davies

*1: Transcript of conversation with Renard, July 16, 2022.

*2: Interview fragment, David Sylvester and Cy Twombly, Art in America, July 2000.

*3: Charlie Renard, POS A DAR, edited by Virginie Kastel (TRESNUBES ediciones, 2019).

*4: [Translator’s note: in Mexico, a holiday party is known as a posada.]

*5:Transcript of conversation with Renard, July 16, 2022.

*6: Charlie Renard, Bitácora de la Multiplicidad (2021).

*7: Charlie Renard, POS A DAR, edited by Virginie Kastel (TRESNUBES ediciones, 2019).

Published on August 21 2022