Interview

The Success of Our Failure: Interview with Cecilia Vicuña

by Fabiola Talavera

Retrospective at MUAC

Reading time

8 min

Based on how I had conducted past interviews, I had hoped to speak with Cecilia Vicuña face-to-face, conversationally. It was not to be. Although a retrospective exhibition of her work recently opened at the Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo (University Museum of Contemporary Art, or MUAC), when I set out to contact her, Vicuña had already returned to New York, the city that welcomes her these days.

Given the possibility of either making a phone call or sending an email, I opted for the latter course. Phone calls have always panicked me. A few weeks later, the remote interview was no longer a contingent circumstance, but a necessity. The Covid-19 pandemic had forced us to take distance from each other. Besides that, this global situation has forced us to be always available behind a monitor. Where else could we be if not in our homes? Still, I think that leisure time and reflection should be respected. An email will always be much less threatening than a call, something that demands immediate responses.

The exhibition titled Veroír el fracaso iluminado (“Seehearing the Enlightened Failure”) takes us on a journey of more than a hundred works that Cecilia Vicuña has carried out over several decades. Her explorations have always traversed between multiple disciplines, from sculpture to painting, from performance to video.

The first works of her career were carried out in 1966. Vicuña created small sculptures from debris found on the beach of Concón, in Chile. She titled this series of fragile nature Precarios (“Precarious Objects”).

The precarious was born by itself, without premeditation or scheming. I felt that the sea felt me and I wanted to respond, I planted a stick in the sand, as a sign for the sea to erase it. Thus began my dialogue with the sea.

Vicuña rearranges organic and inorganic elements, such as wooden sticks, bottle caps, feathers, fabrics, and threads, all in order to create ephemeral sculptures that will eventually be swallowed by their surroundings. Like the spoken word that’s activated when launched into the air, the Precarios function as a spell to dialogue with earth. Vicuña tells me that in 1954 the Chilean government had already installed an oil refinery in Concón, an ancient pre-Columbian site. The disappearance of the sculptures is for her a way to regenerate life, using as her raw material waste that was discarded in accordance with consumerist logic.

As Vicuña was beginning her artistic practice in the mid-sixties at the margins of institutions, Ana Mendieta, in North America, was connecting her body with the earth in symbolic acts. That time also saw the emergence of the Land Art movement, driven by commercial galleries focused on preserving the photographic record of monumental works left to the fate of their environment. However, for Vicuña, in the 60s and 70s, South American art had not yet been invaded by the pressures of the art market. “We were free to imagine another reality,” she remarks.

Beyond anecdotal accounts, very few photographic records of the early Precarios exist; but Vicuña’s dialogue with the sea would not end in Concón. In 1990, Vicuña inaugurated an exhibition at the Exit Art gallery in New York, where she presented a series of Precarios under the name Pueblo de Altares (“Village of Altars”). Similar to that installation, the MUAC retrospective presents on a sandy beach around eighty Precarios made from the 1980s to the present day.

In Chile, Vicuña founded with her friends La Tribu No (“The No Tribe”). Operating between 1967 and 1972, the group was in charge of generating playful actions that history would come to call “happenings.” I asked her how this group was formed and what they were saying no to.

First I wrote the No manifesto, saying NO to the world as it was, affirming another way of being, then, I realized that it would take a tribe to bring the manifesto to life, I made the No membership cards and waited for my friends, telling them “now we’re La Tribu No,” they laughed and didn’t care. In this way I knew they really were La Tribu No.

With a scholarship from the British Council, Vicuña went to study in London in 1972. A year later Chile suffered a military coup by the Chilean Armed Forces, overthrowing the country’s leftist president, Salvador Allende. After this event, Vicuña sought political asylum in England.

The coup was world-ending for all who, like me, were nourished by the spirit of justice and joy that animated Popular Unity [Allende’s coalition]. Everything I knew and loved fell apart. Being near or far didn’t alter the pain.

In response to these events, Vicuña, still in London, along with David Medalla, John Dugger, and Guy Brett, formed the organization Artists for Democracy. Together they organized a festival and an auction that mobilized artists to create works for the benefit of the Chilean fight for freedom.

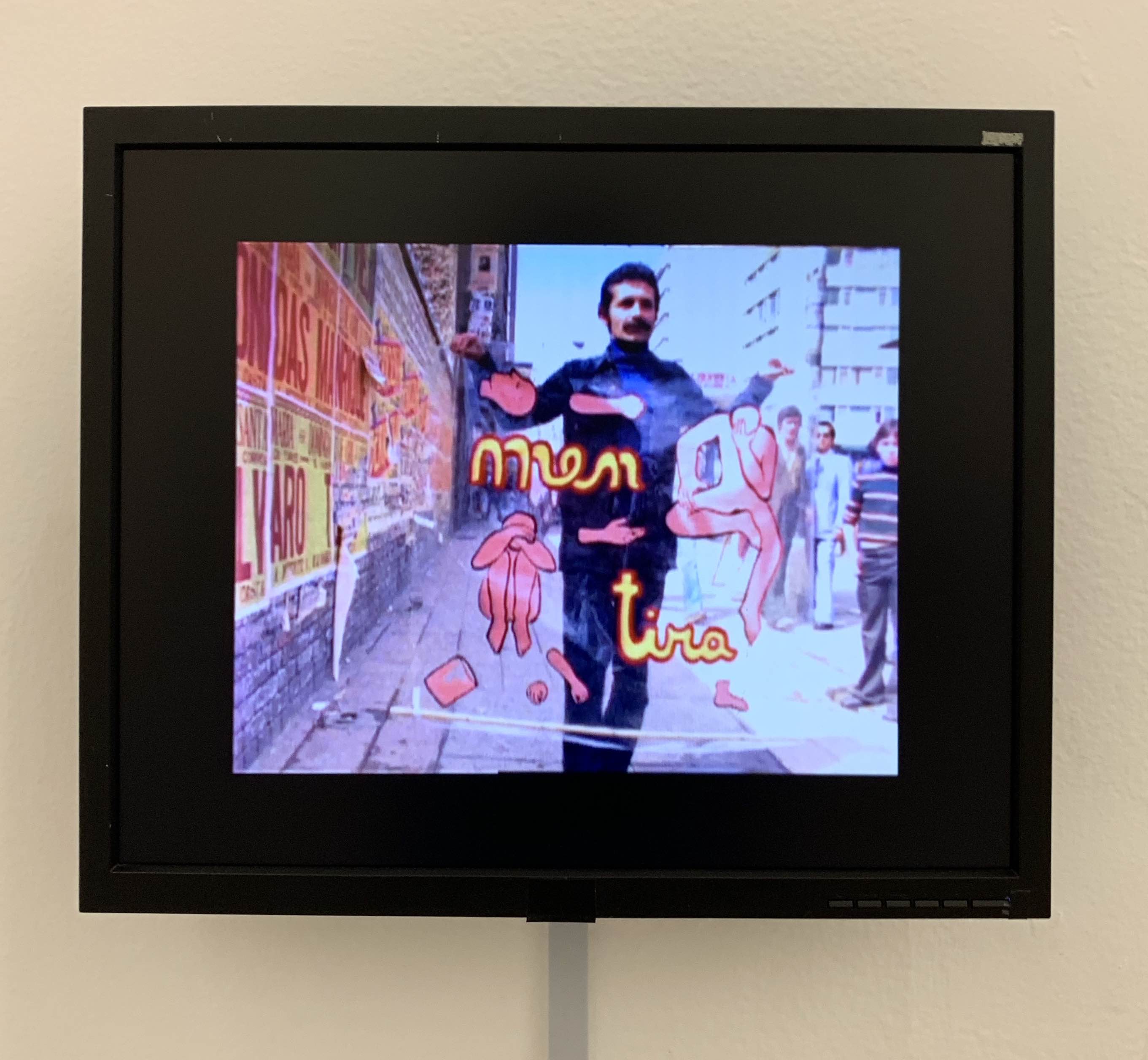

As an unarmed tactic in the face of the lies propagated by the coup government, Vicuña in 1973 conceived the series Palabrarmas (“Wordweapons”), which sought, through visual reflections and live actions that dismantle language, to reveal the poetic and political effects that words have on reality.

Words inter-act with reality, whether we are aware of it or not. The world would change if we saw language. Perhaps one day the consequences of language will be understood, as well as the consequences of the hatred that has generated wars, massacres, and dictatorships. Lies and “fake news” now dominate because we don’t practice seehearing, the art of discerning truth from lies.

Veroír (“Seeinghearing”), the neologism present in the exhibition’s title, is a Palabrarma (“Wordweapon”): “it’s a new verb for the act of seeing hearing, with awareness of our perception.” As far as the meaning of the second part of the title, el fracaso iluminado (“enlightened failure”), Vicuña prefers to leave it as a riddle.

… I can say that from an Andean perspective, our species’s “success” is also our failure, since we are destroying the biosphere, liquidating wildlife and its species. At this rate, we are accelerating our own extinction.

Much of Vicuña’s work revolves around water and the bodies that carry it, such as the beaches of Concón, the creeks of New York, and the streams of the Andes. For her, water is “the communicating vessel, the connection that maintains life on the planet.” A finite resource that’s now scarce, Vicuña remarks that already in the 60s it was known that water was in danger: in Chile the dictatorship privatized water, leaving close to 4 million people without access to it.

In 2010, Vicuña returned to Concón, birthplace of her art, in order to make the documentary-poem Kon Kon (2010). In it she contrasts rituals of offering to the land, flute orchestras, and Chino dances local to central Chile, to the destructive forces of globalization, which materialize in the privatization of natural resources, the imposition of the oil refinery, trawl fishing, and the destruction of sand dunes.

I ask Vicuña about the role of art in preserving memory beyond history as it is given to us.

Art always constructs memory, our acts also construct memory, everything contributes to that continuous creation. You have to think about what kind of memory we are constructing day-by-day. I remember the day I came across an African sculpture, which bore a note from its creator, saying: “among our people everyone prepares to be a good ancestor.” An ethical code thus emerged. Awareness of the power of memory would affect behavior. The trace we leave connects us with that ancestral future.

If one makes an account of her work, one observes an idiosyncratic tread through art beyond official canons and circuits, a practice that seeks to heal symbolically our relationship with the earth by proposing a new political way of perceiving and acting in the world.

The Precarios’ basic principle insists on their inevitable disappearance. Like life itself, sooner or later everything disintegrates. A global situation has led us to a slowdown in our activities and to an uncertainty about the future, one that puts into question so-called “productivity." Above all, it has forced us to live in the now, to feel our constant transformation in a relentless flow of history. Vicuña, towards the end of Kon Kon, reflects on fading Chino traditions: “while they are singing, while they are dancing, that wordless sound of the flute, here there will always be life, here there will always be wind, here there will always be words.”

Virtual tour of the exhibition Veroír el fracaso iluminado at MUAC

Published on May 14 2020