Essay

The Ion-Ara-Macao: On the Work of Luis Figueroa

by Christian Camacho

Reading time

6 min

Is color an animal?

Sounds unlikely.

But what then is an animal?

Michael Taussig

For them color is fluid, the medium of all changes

Walter Benjamin

Luis Figueroa is an artist currently residing in the city of Monterrey, whose practice I have come to know through a pleasant approach, one that is less and less distant, and that little-by-little becomes face-to-face, from the west side to the north side of our shared city. His work has crossed my path at just the moment in which my curiosity has piqued: not only in terms of establishing a dialogue with what is taking place in Monterrey’s painting scene, but also in terms of the personal need to enter or re-enter—perhaps permanently—that part of color’s operations in painting, with painting, that cannot be avoided while making it, imagining it, or sharing it. For me, it is a source of great healing to rethink color and to look at Figueroa’s work while influenced by this recurrent interest.

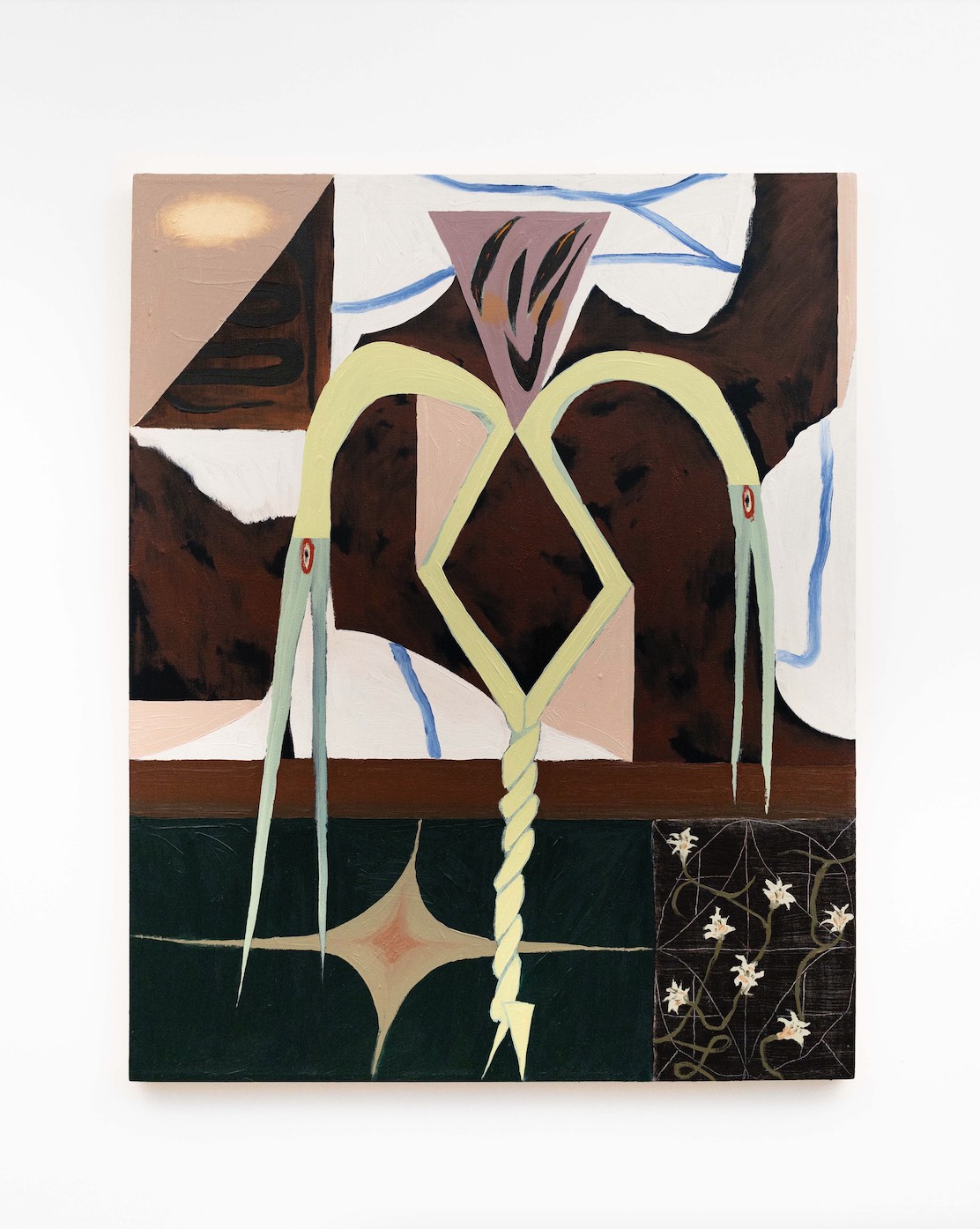

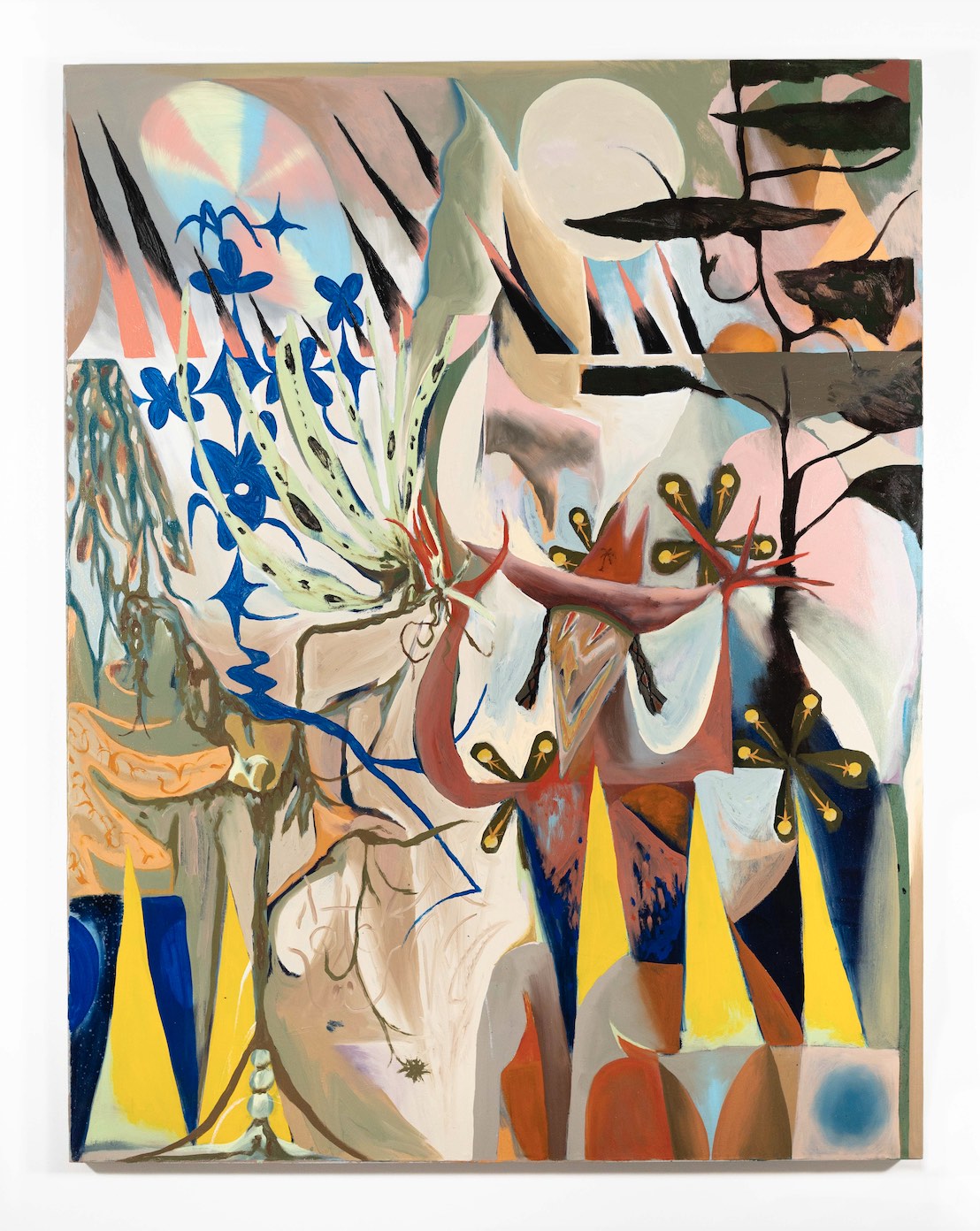

Observing Luis Figueroa’s painting is a nearly instantaneous unpacking of options: the immediate leap into a starting position and a slight jolting of expectations. Almost no area offers the gaze a prolonged landing, or a place where contact renders a pool of color more serene. The presence of neighboring vibrations quickly reintroduces the general buzz that animates the never-still intentions of the work’s figures.

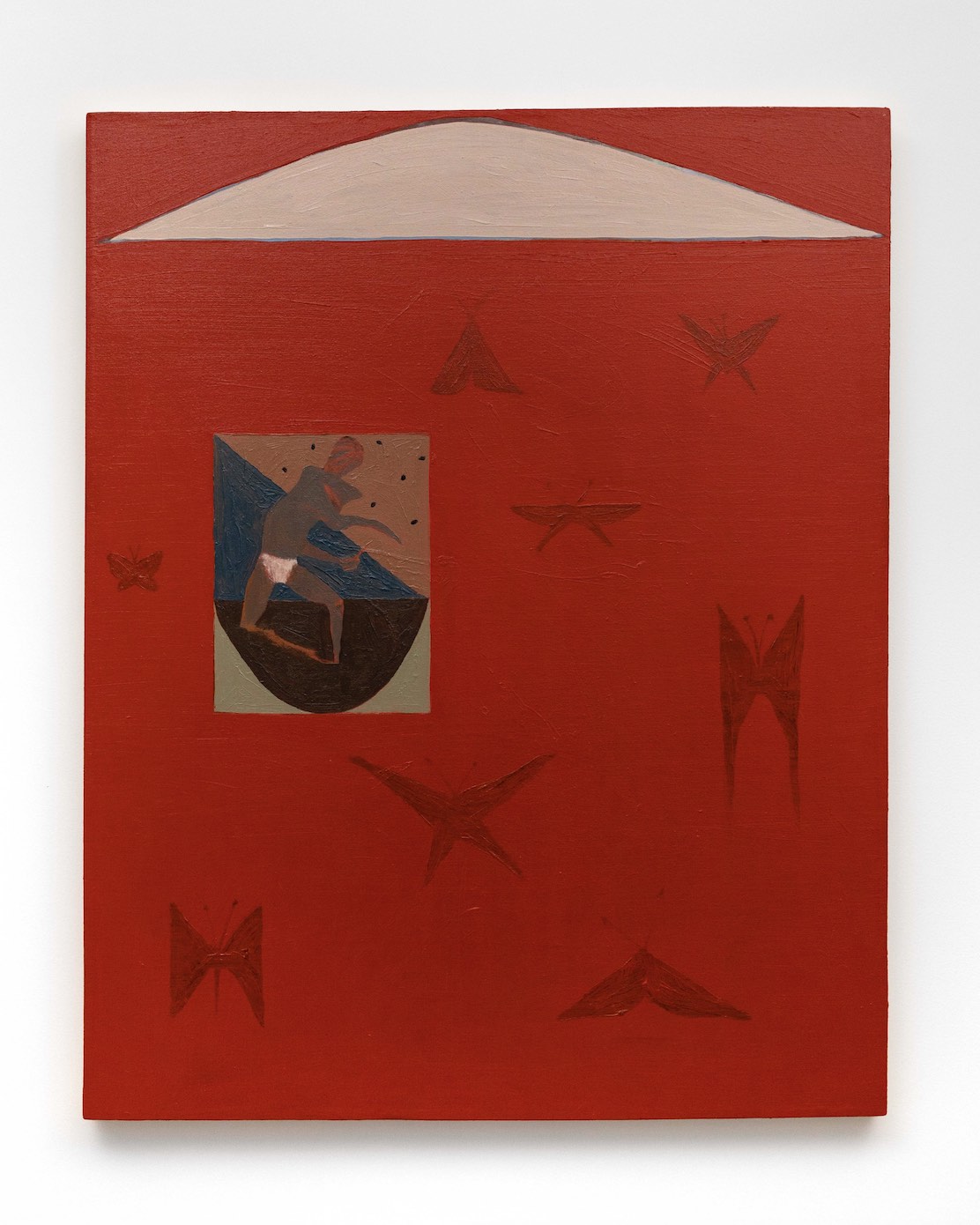

The presence of this figuration is also inviting, and its arrival announces issues that I consider of great importance to Luis Figueroa’s work. First of all, the figures exist in a continuous-but-woven plane between dimensions of color: they delineate their valleys, their peaks, their interiors, their exteriors. The figure is the face that is often provided this painting’s most specific decisions: the singular or double use of the triangle, the rhombus on the torso, triangular extensions verifying correspondence between eyes, mouths, hats, and vegetation, the recurrences of characters in shapes (and vice versa), as well as the illuminations that populate their flamboyant settings. In Figueroa’s painting there seems to be a constant indeterminacy among those activities that his beings carry out day and night, under a scorching sun or under the earth, into which the color has seeped.

I do not consider secondary for Luis Figueroa’s work its metaphors lying between territory and color, nor do I speak insistently about the presence of activity or life. Thanks to the influence of anthropologist Michael Taussig, whose work Figueroa has kindly shared with me, the artist has come into contact with Benjamin’s and Burroughs’s ideas on color. Not only with their affirmative possibilities, when they are not totally liberating color’s invocation in the face of the chromophobia of the colonizing west (inorganic color or [the conquistador’s] chromicidal body armor – What Color is the Sacred, Taussig, 2009), but also with color’s infiltration in the metabolisms of all societies, of those nourishments, appetites, and famines that can be linked to the dispersion of color. Burroughs’s well-known color walks can mean many things to many people. For me, one of those meanings points to the fact that signs of color flow throughout the environment with or without interests, and are a part of a life that is understood because it is lived in passing. Going for a walk about color, thinking about color—indeed. Cooking about color or dressing about color or talking about color as well. I don’t know if anyone wants to eat about color, but perhaps that too.

In any case, painting about color is both expected and surprising: a sequence of nuclear and constant contacts with previsions of painting that sooner or later spread and mutate against the best preparations, expectations, and abilities. Luis Figueroa’s work reminds me that on many occasions the painting we do is one with which we gradually learn to live. Its colors also become those of our enclosures and a specific but indecipherable key to the inner forest of our signs.

I remember with pleasure a very brief talk I had with Luis the first time I saw his work in person; it involved the title of a piece. El preso guacamaya [The Macaw Prisoner]. I spent a long time thinking about the strange relationships between salsa music, prison, and the animal world. This extremely rare prognosis for a work, which also somehow gives this text its title, was in fact confronted by a complex painting. A setting in parts that quickly intertwines blue patches and lands with the familiar but nervous repertoire of stars, birds, and undulating smiles that never allow us to affirm with total certainty if a painting is sad or happy, or if its characters are suspicious or to be trusted.

It was also here that we talked a bit about yellow and its mysterious place in both paintings and flags. In this, there is something I consider very deliberate and precise about Luis Figueroa’s painting: its frontality, although fractured, has been executed without attempts at any saving spatial illusion. The invitation to signs, whether woven by a ritual geometry or by the ever-present mystery of the masks constituting their triangulations, is direct. I consider this a mark of conviction for the few words that sometimes precede a serene but serious alliance with painting and its long-term life of color. Solving head-on the proverbial death by maximalism, things are sometimes complicated, sometimes not.

Looking at the works by Luis Figueroa that accompany this text, I also notice the picture’s edges as a system of limits in itself, and I think of the sharp figures inhabiting it. These forms take up his painting with a very clear awareness of the limits of this moment and of its pleasant or dizzying gravity. With this, I recall an idea that I found in one of the works by Taussig that Luis shared with me and with which I would like to close this text. Thinking about the teepees that various North American native peoples built as habitations out of bison skin, Taussig asks us to

imagine what it might be to sleep and shelter inside an animal this way, to be inside the buffalo, in this crucible of transparent color. This would make a nice complement to having wild animals inside your body. During the day, let us say, they live inside you. At night you live inside them. Such is color.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

Published on October 4 2021