Review

The Impossibility of Reconstructing the Lived Experience into a Rational Whole: On Carla Rippey and Agustín González at Arróniz Gallery

by Nico Barraza

Reading time

6 min

Had there ever been a work of art that wasn't laden with the expectations and prejudices of the viewer or reader or listener however learned and refined?

— Siri Hustvedt*

Carla Rippey and Leticia Arróniz, who was working at Galería Ponce, met shortly after Rippey's arrival in Mexico in the 1970s. Years later, Arróniz had a son named Gustavo, who, much later, upon taking over the gallery in 2006, invited a group of friends/artists and colleagues to join him on his fledgling journey. One of them was Agustín González, who was a student of Carla around 2001 at the National School of Painting, Sculpture, and Engraving "La Esmeralda," where an incessant artistic collaboration between them originated. I, having nothing to do with that context, was reading Lauren Beukes' Bridge over the weekend when Rippey and González's project was inaugurated. The novel is about alternate realities and the journey the protagonist undertakes through them, seeking answers about her mother. The coincidences that seem like connections captivate me more than they obsess me: it's from transient details that permanent obsessions arise. So, entering Arróniz to see an exhibition titled Viajeros en el tiempo [Time Travelers] engaged all my senses and musings.

Curated by Michel Blancsubé and Maria Giner de los Ríos, the project brings together a body of recent work where each artist's practice and style shifts and confronts, tenses and softens. An intergenerational dialogue that delves into shared interests and a creative collaboration woven over the years. And it is precisely time (fragmented) that takes center stage in the scenes unfolding along the gallery walls: the helplessness of rearranging lived experiences into a coherent whole.

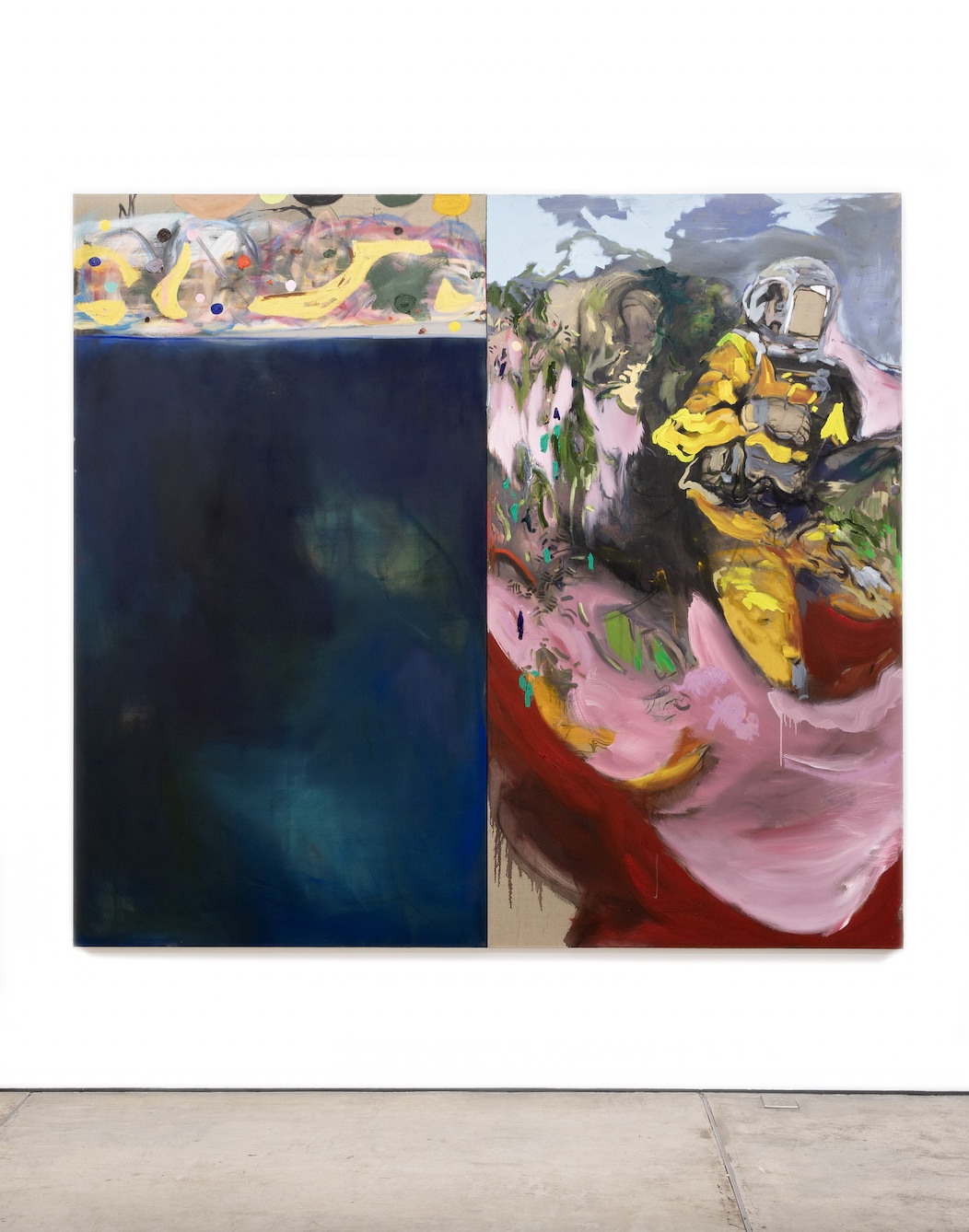

Agustín González presents a series of paintings that Blancsubé describes as a journey through time. Moments, if they are indeed moments, (dis)appear right before our eyes, a lifeless tide of vibrant, powerful, and bewildering color. Movement in the static, our sensation adheres to the artwork. Vague and nebulous images are a kind of covering for the mental gaps caused by lost but not forgotten times. They reveal a half-finished landscape, an astronaut, a jacket. In any case, and whether this is true or not, González has already transported us to another place. The pictorial experiments arise from reading and the nearby, from those transient details I mentioned earlier. The paintings left me pondering what is learned: what remains, the precise details, traces of the past that shape our present. What of what we leave behind will endure? What will disappear? Can we really intuit what we are? Do we even understand what we were? Disassemble to understand... to move forward.

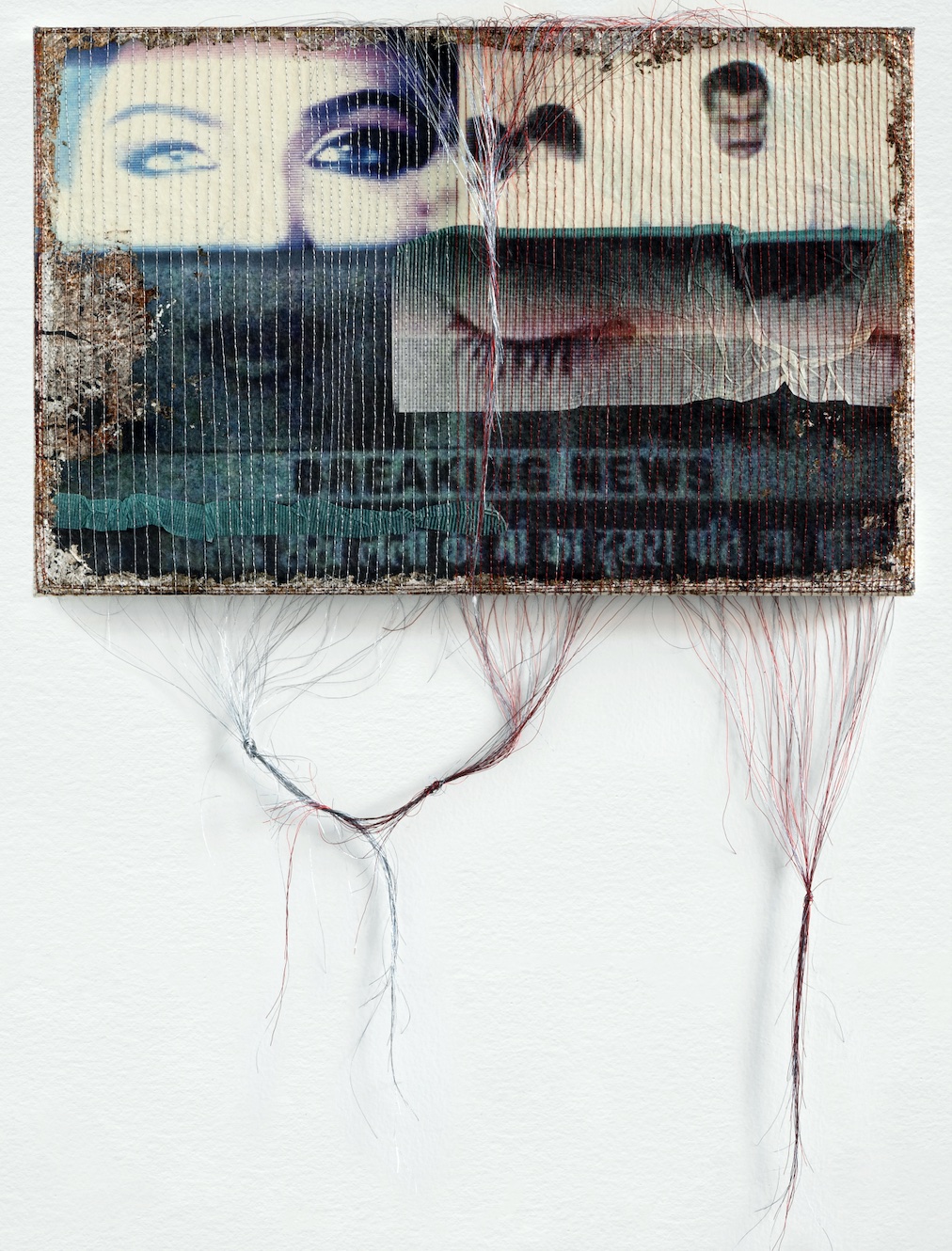

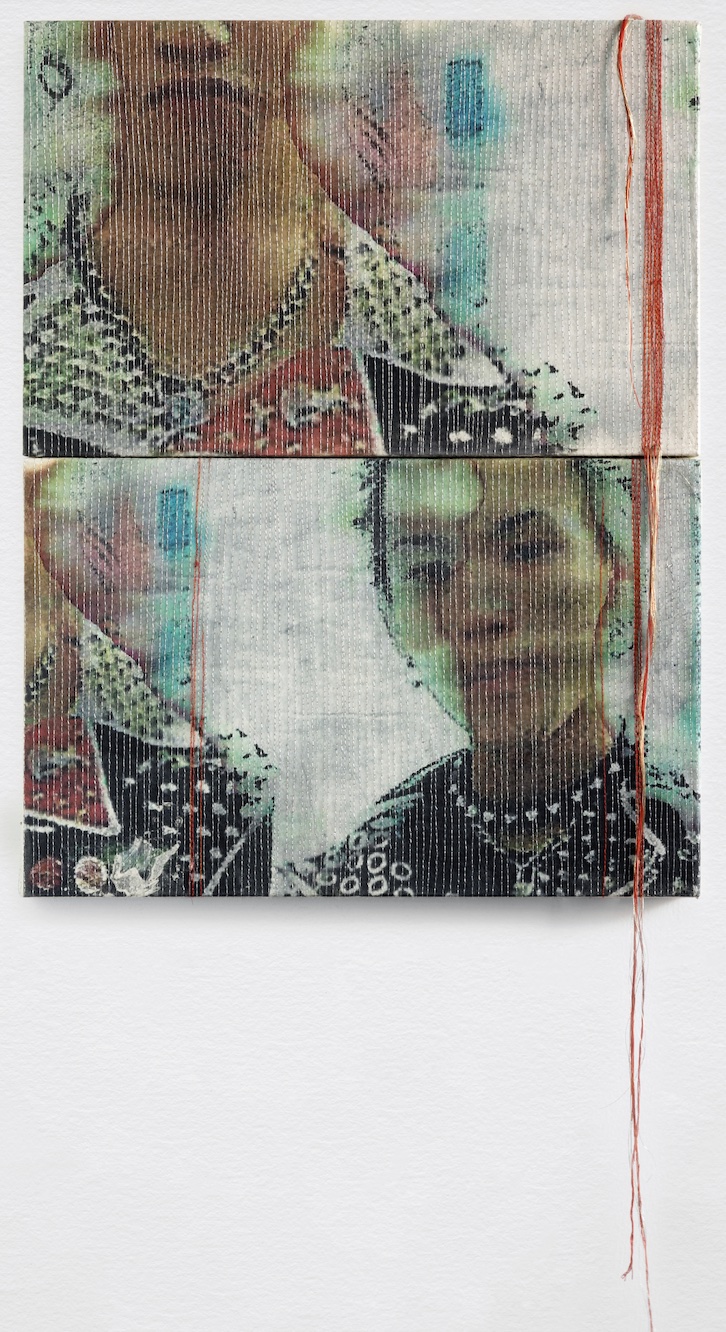

Carla Rippey continues the journey with a series of photographs taken in Cambodia, derived from screenshots of a television and a book by Shoichi Aoki. Linked to the theme of memory and permanence, threads hang and intertwine over the photos. By this point, I was already in a universe similar to that of La invención de Morel [The Invention of Morel] or El imperio de Yegorov [Yegorov’s Empire]; I couldn't stop thinking of the threads as roots that we sow in our memories, strains that our memory needs to persist. Because while Rippey takes the images from a specific context, it reminds me of what Bioy Casares (being Morel) declared about the aura that every image possesses. The reading mutates every time we remember something: what we thought we lived a month ago is already different from how it is currently thought, how it was digested at that moment, and, of course, radically different from how it actually happened.

The act of sewing as something analogous to the mental/emotional process we undergo when choosing what we will remember (where the needle pierces), what we prefer to alter, reinvent, or recompose (the spaces between holes), what we await to happen, the uncertainty (the hanging threads). Something that Rippey clearly does with the images is decontextualize them to later recontextualize them, so it's inevitable that spectators distort the intentional to turn it toward the personal. It reminds me of Hustvedt's book, El mundo deslumbrante [The Blazing World], where essentially multiple perceptions are read about the same person that all the characters supposedly knew. Not everything we are is expressed through words, not everything we were is known through a single author. We are layer upon layer upon layer.

Both artists propose alternate worlds linked by their similar future and contiguous origins. The work dialogues because none of it intends to guide us to a specific place but rather allows us to wander through our past and uncertain future. Where are we, and where are we headed?

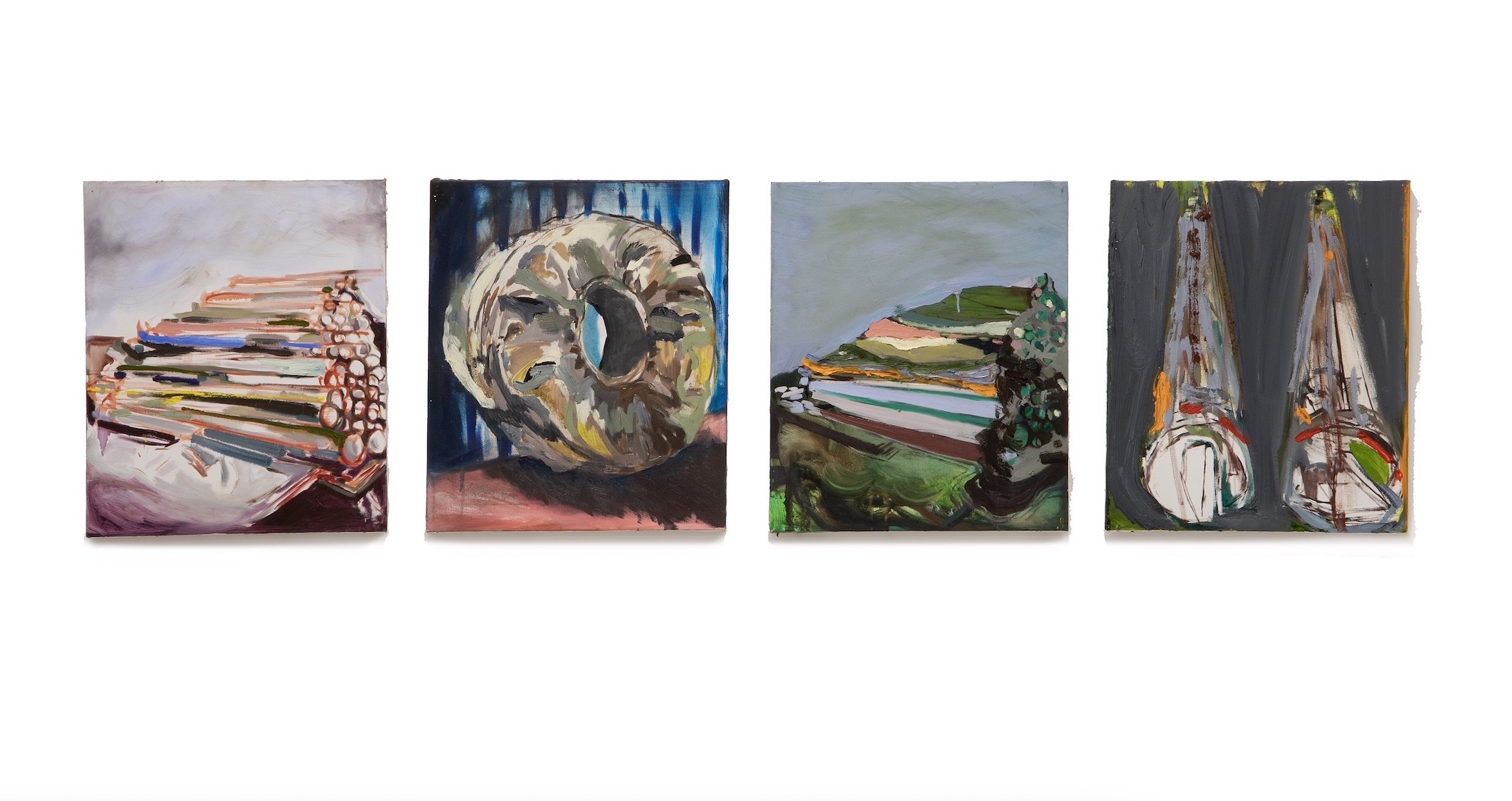

The wooden structures located in the last room are an ambiguous reconstruction/interpretation of engraving plates, a practice shared by both, and probably worked on in both distinct and similar ways. The work reflects the discrepancy that every human being faces when confronting another: we are similar, but not, we come from the same place, but not. It's important to consider that Carla was Agustín's teacher, important to value that we are all teachers and yet still remain students.

In this coming and going of realities, coincidences, and connections, it's not surprising that the exhibition ends with the production that initiated the project, a series of posters and drawings created by both where the synergy in the creative process and the dialogue they engaged in are clearly perceived. The series makes me reflect on the complicity of moving towards a dreamlike and nonexistent place, but one that undoubtedly calls us and emphasizes the place where we actually stand.

The exhibition left me thinking about fictional scenarios and reliving what now seem like staged scenes of my memories. If there's one thing I can affirm about both Rippey and González's work, it's that both manage to transport us to a foreign and yet personal delirium.

Translated to English by Sebastián Antón-Ojeda

*: Siri Husvedt, The Blazing World, 2014

Published on November 24 2023