Essay

The Aura is Back with a Vengeance. About Rafael Lozano-Hemmer

by Cristina Torres

Reading time

8 min

When it was suggested to me that I write about the work of Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, I thought of that ancient metaphor of not being able to step into the same river twice: of our languages’ difficulties in tracing what remains and what doesn’t, that is, in writing a text with the memory of a few intervening years and a trip to a cube different from the one in which I first came to know his works in person.

Latidos at Espacio Arte Abierto

The encounter begins with an undulating journey into a reflective prism marking the center of a plateau of lush green grass, geometric fountains, the steady glow of dozens of shops, underground spirals for cars, and still more reflective prisms of steel and concrete. Espacio Arte Abierto, the center for architecture of the homonymous association (“Arte Abierto”) linked to Grupo Sordo Madaleno and located within Artz Pedregal, opens its exhibition program with Latidos (“Pulse”), Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s third exhibition in Mexico City, made up of four participatory installations focused on translating biometric readings of visitors into impulses of light, sound, and movement.

The first work is located at the entrance to the lobby, between the deterritorialization of the commercial landscape, the architectural familiarity of the artistic institutions, and the stagnated access to the gallery owing to sanitary measures. Commissioned by Arte Abierto, Corazonadas remotas (“Remote Pulse”) consists of a pair of podiums on which two people can place the palms of their hands, and, in doing so, perceive a vibration that emulates at a distance the other’s heart rate. The initial plan was to connect the exhibition’s visitors with the Museo Amparo, but, faced with changes in the influx of COVID-19, it was decided to create the communicative bridge with a nearby terrace within Artz Pedregal. In 2019, the same work formed part of the project Sintetizador fronterizo (“Border Tuner”), in which a technology-mediated bridge was put forward between El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua. The experience is drastically resignified in its new context: from a story in which a series of hi-tech impulses traversed one of the most violent lines on the planet, to that of a project worker looking back to us from one of the city’s most luxurious shopping malls.

Sanitizing gel, sensor, light, sanitizing gel, sensor, light + sound, sanitizing gel, sensor, light + sound. A new choreographic loop in which asepsis is inserted into an experience where contact between machine and skin opens the decisive moment for a certain idea of participation.

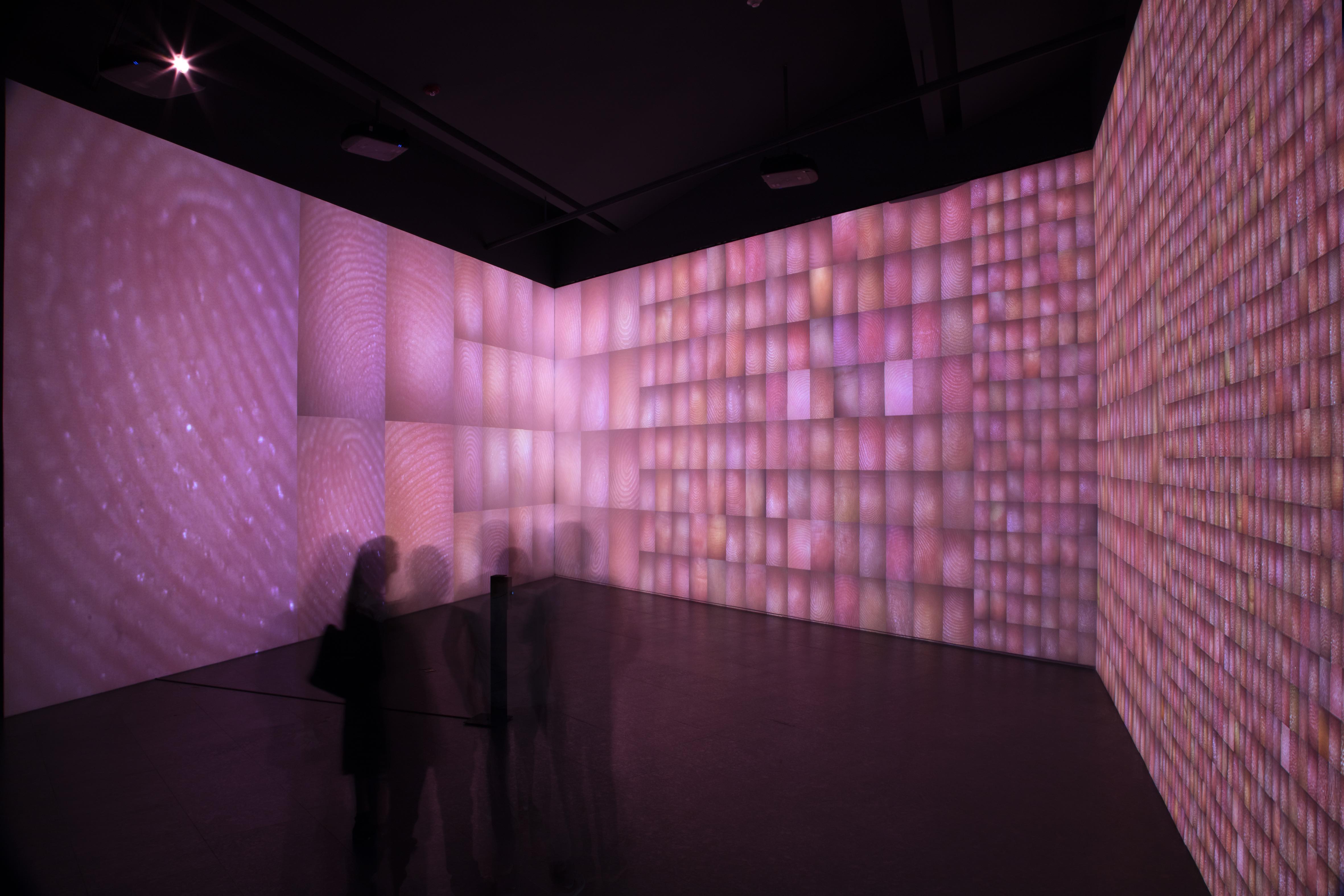

Once one is inside the gallery and within the dark atmosphere that often characterizes Lozano-Hemmer’s works, a reticulated tapestry projects the luminous and magnified fingerprints of previous visitors. Índice de corazonadas (“Pulse Index") allows visitors to place the homonymous finger on a podium with sensors and then view their monumentally magnified photo on the wall alongside a graph of their own heart rate. The accumulation of data displaces the fingerprints to the opposite side of the tapestry, making them smaller and smaller, until they progressively disappear from the archive. This mechanism common to several of the artist’s works—gathering of biometrics, change of scale, and magnified socialization of the evanescent archive—points towards the increasingly urgent issue of privacy and data in our context of hyper-surveillance, and, at the same time, towards the astonishment produced by public amplification.

In the middle gallery, Tanque de corazonadas (“Pulse Tank”) again measures the heart rate of several people in order to translate it into mechanically formed waves on water mirrors that are later refracted towards the walls and ceiling of the space as light and shadow. As in other works, there is an interesting, very brief interlude between the instant of body-sensor contact and the response of the work’s mechanism. And then what we’ve been waiting for appears: seeing fragments of our bodies interpreted by circuits, perceiving ourselves through machines and stages, how do we choose the mirror in which to seek our reflections?

The tour ends with Almacén de corazonadas (“Pulse Room”)—one of the artist’s most celebrated works—in a room with hundreds of lightbulbs hanging from the ceiling, each one flashing at a different time interval while an intense sonic environment reminds one of something between a roar and the waves of the sea. The room pulses with the rhythms of the most recent visitors’ hearts, each lightbulb manifesting the register of a singular rhythm. The work’s choreography first displays the chaotic set of sounds and rhythms that generate silence when someone decides to yield their biometrics, exhibiting a kind of solo show, until the system integrates them into the group and the chaos returns. I remember first encountering this work five years ago at the Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo and the intense feeling of synchronicity between the lightbulb and something inside me. On this occasion, neither the work, nor the context, nor I were the same. I was first able to observe others take their turns. Then, when my turn came, and, to my surprise, it demonstrated to me something like techno music, we all laughed.

I had the opportunity to see the exhibition on a Sunday, together with families and strolling couples. As someone who works by conversing with people about art, I have the impression that art history and criticism would benefit greatly if they approached other people’s receptions of works—the other art (hi)stories. If this is true for any art experience, it’s perhaps more so for those that are self-styled as participatory; however, I decided not to approach anyone for conversation in order to respect the present social distancing. In general, I saw smiles and gestures of astonishment, especially in young children who wanted to be the first to pass: their eyes widened and leaped after watching the works’ responses to their bodies.

It’s impossible to know how many reflections emerge about contemporary surveillance, the idea of contact through hi-tech translation, the role of art in the public sphere, the progressive digestion of art spaces in shopping plazas, or what it means to participate: if it’s about feeding ephemeral archives, or if “we have never participated,” as the 8th Shenzhen Biennale, curated by Marko Daniel, declared.*1 In a talk organized on the occasion of the exhibition, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer questioned the optimism that usually surrounds concepts such as light—which he associates with violence and artifice—as well as the collective and participation. Regarding the latter, he mentioned that, although not necessarily positive, it at least preserves the specificity that the age of technological reproducibility announced as lost, or in his words: “The aura is back with a vengeance: participation.”

The exhibition will be open until December 13. More info here.

The Bodies of Memory

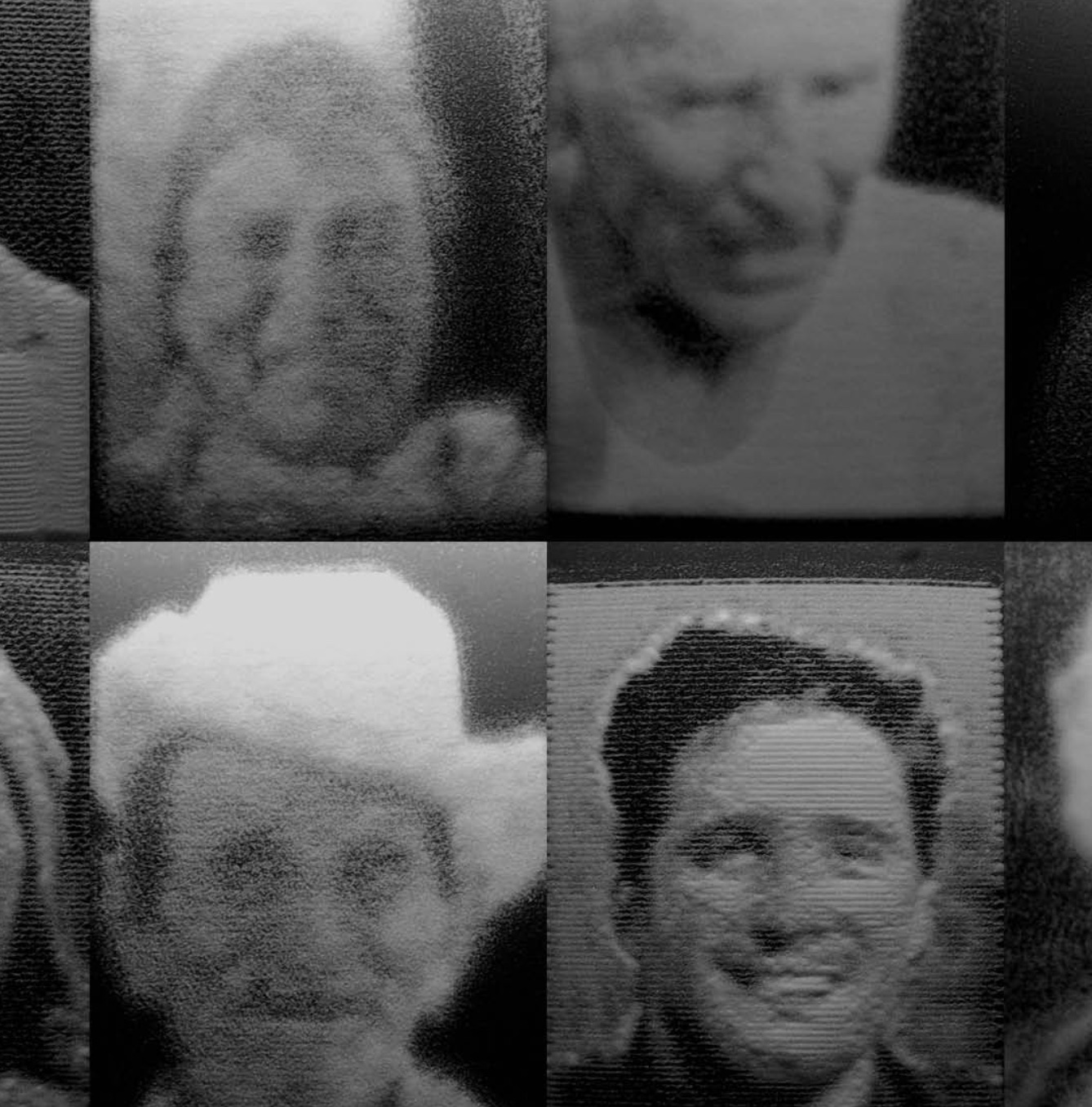

The Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo presents La arena fuera del reloj. Memorial a las víctimas de COVID-19 (“A Crack in the Hourglass: A Memorial for the Victims of COVID-19”), a virtual exhibition by Rafael Lozano-Hemmer dedicated to creating an online memorial to those who have died as a result of the pandemic. One year after the portraits by Ai Weiwei of the 43 Ayotzinapa students and five years after Lozano-Hemmer’s solo show, the MUAC hosts a new wall with victims’ faces, this time drawn with sand using an electronic device and incorporated into a collective online archive.

The entry on the site says: “We are waiting for an image of your loved one. Click on the link ‘participate’." A real-time video transmission shows a grayscale scene awaiting photographs in order to begin the work’s technological translation. To do this, a form must be filled out. Each entry shows the person’s name, their date of birth, the original photograph, their image traced in sand together with a video of the process—bearing some similarity to the opening sequence in the Westworld series—as well as a written dedication and buttons for sharing on Facebook and Twitter.

Inserted within the long history of funeral images created to accompany the difficult work of mourning, La arena fuera del reloj offers “a shared altar and a ceremony adapted to 21st century technology and living conditions;”*2 a specific mediation from within the digital interface, a machine that draws using sand, and an archive of the experience of an irreparable loss in an extremely delicate context. Beyond the evanescent symbol of the hourglass, the iconicity of the face as a person’s identity, and the hi-tech translation, a couple of questions stick out, looking for answers: What is the social role of the museum in the management of this planetary mourning? And, above all, what are the bodies that we will give to memory?

More info about A Crack in the Hourglass here.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

*1 We Have Never Participated was the title of the 8th Shenzhen Sculpture Biennale in 2014.

*2 Cuauhtémoc Medina, from the curatorial text.

Published on November 13 2020