Review

The Anarchism of Eunice Adorno: Retracing History in Order to Intervene in Memory

by Stefanía Acevedo

At the Museo de la Ciudad

Reading time

6 min

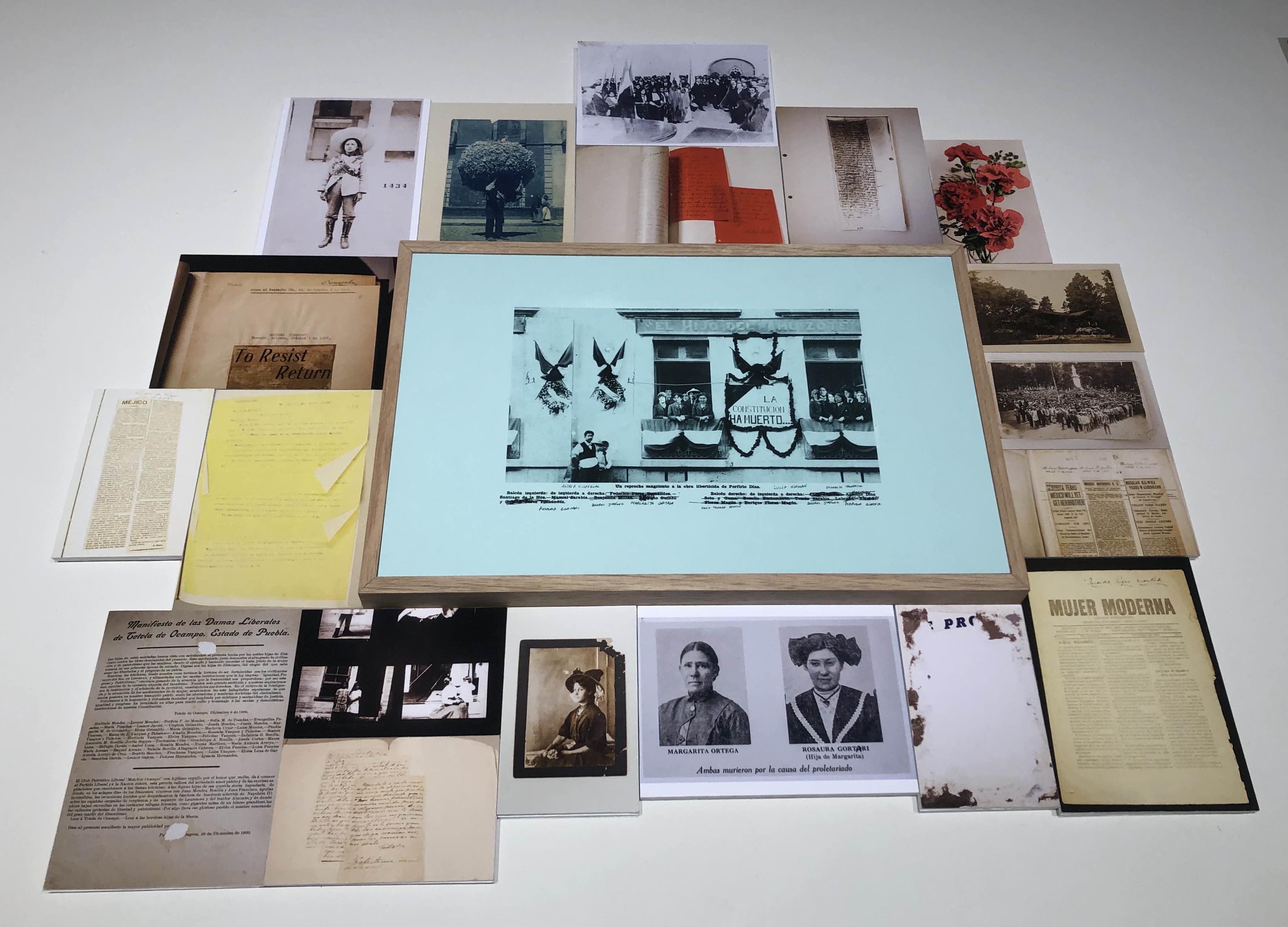

Eunice Adorno (Mexico City, 1982) presents Desandar (“Retracing”) in the Museo de la Ciudad. This show, curated by Allegra Cordero di Montezemolo, exhibits archival material that works like raw material: at least six collections, archives, and libraries were consulted in order to select documents that were intervened-in through copies and photographs, using inks that form colored stains, as well as clippings and collage.

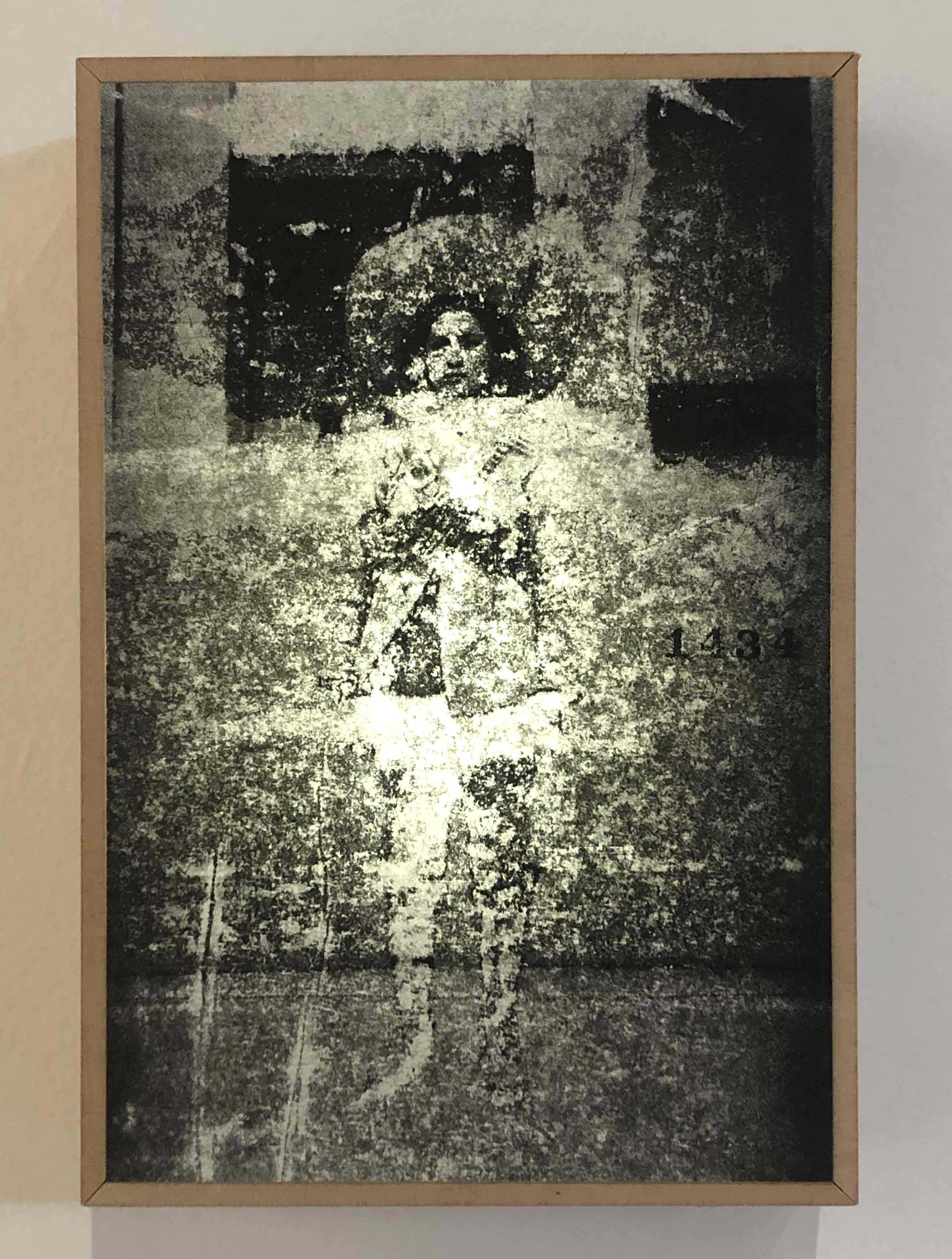

It all started with looking for clues, traces that allowed the artist, who is also a documentary photographer, to create narrative fictions. This not only resulted in the selection of the particular documents that form part of the exhibition, but also in an aesthetic approach in which the color of wear-and-tear takes on different shades. Sometimes we observe the classic black, white, and sepia that we associate with the distant past, although we also encounter such other colors as pink, green, and blue. These contrasts are evidence of the fictional and playful character that runs throughout the entire show, but also of the presence of ghosts that she desires to invoke.

Adorno interrogates the documents in their meaning and in their presentation. Desandar shows work that delves into the assembly of History and the modification of images that constitute it, taking archival research as its starting point. Its objective corresponds on a conceptual level with its plastic operations: to make visible the fundamental role of women in the Mexican Liberal Party (usually associated only with the Flores Magón brothers), something still practically absent in histories of anarchism in Mexico.

The works can be separated out into an installation, a collage series (made using reprography, a process for reproducing documents through different techniques in which a machine’s ink intervenes), light boxes, a mural, a documentation table, as well as intervened-in documents and photographs. The pieces camouflage each other, in such a way that we find together the Manifiesto de las Damas Liberales de Tetela de Ocampo (“Manifesto of the Liberal Ladies of Tetela de Ocampo,” 1900), period newspapers and letters, as well as photographic interventions in documents and images. Some interventions are obvious and others are shown more subtly.

Adorno avails herself of History’s fictional nature and the arbitrary selection involved in the construction of an archive. Hence the combination of the intervened-in pieces and the reproduction of the original documents makes visible a position regarding how the past’s narration is constructed, and also regarding which methodological processes legitimize it. In the exhibition’s assembly, as well as in the different pieces’ production, History is implied to be a process that cannot fail to be accompanied by the imagination: the imagination of what was not recorded.

Among the pieces, the installation Falda dinamita (“Dynamite Skirt”) is a tent presenting the lives and ideals of six anarchist women: María Talavera Brousse, who, before being recognized for her crucial participation as a Party organizer, had been reduced to the role of Ricardo Flores Magón’s partner; Lucía Norman, activist in the labor movement; Margarita Ortega, weapons expert; Andrea Villareal, founding journalist of La Mujer Moderna (“The Modern Woman”); Elizabeth Trowbridge, teacher; and Ethel Duffy Turner, poet and editor of the English version of Regeneración (“Regeneration”). In addition, the tent contains drawings by different artists, as well as red sewn pieces that highlight parts of the women’s biographies.

In front of this installation we find a mural composed of stains and inscriptions, as though they were remnants of some presence; seeing them from afar, one has the feeling of being in front of a kind of pattern formed by various sheets of paper. The aesthetics of deterioration and wear run throughout the work, as in the light boxes showing photographs by Coronela E. Echeverría intervened-in by the artist with orifices that progressively expose all the image’s missing parts. The original photography can be seen on the documentation table. There is also a notebook with all the show’s pieces, in which we recognize the distinguishing signs of Adorno’s work: paper that is torn, fractured, broken. In this regard, the photographer writes:

I put in this notebook a collection of gestures, fragments, and footprints from the lives of some twentieth-century Mexican anarchist women…In my opinion, these faces are part of their rebel figures, full of utopias and ideals that in this time is necessary for our own feminist history in Mexico…We are linked by their revelation in my present: every stain, every torn document, seems the last of their identity that speaks to me.

The collage allows the artist to show the absolute metamorphosis of the archive. A series composed of four pieces presents surfaces that let us see how photographic work is brought to archival work, where the plastic quality of documents is explored through their pictorial possibilities. What is the color of the past? Adorno responds with her experience in recording with her camera those places where time seems to have been suspended. In the series, the photographer focuses on documents’ materiality in order to take account of something that has been present. The ink, the spots, the folded documents, and the shades of the negatives make it so that photography and archive disrupt each other, showing the fictionality characteristic of both.

As a photographer, Adorno’s relationship with recording the past has not only found a place in her different series of photographs, but also in her Manifiesto de la memoria (“Manifesto of Memory,” 2018), where she explores the inscription of memory as a form of survival, and, consequently, the importance of objects as supports of the past. Adorno says: “the photographic image is the inscription of what is lost.” What is lost finds its re-inscription in the intervention in the archive. Thus, transfiguring the past implies creating other signs of remembrance.

Desandar is a wager in exercising another type of memory, from women and from anarchism, toward incalculable futures. Even in a tradition that has been predominantly masculinized, this opens the possibility of inhabiting a space where feminism generates its own archive, its own images, without needing any recognition other than that of its own power and what it has already deployed. This is precisely what it means to resignify an archive: to leave it open for intervention. To retrace (“desandar”) history is to go back in the road traveled, to erase, to rewrite, and to recognize the images and documents making up all the possibilities of the past that have not yet been written or imagined.

The show will remain up until January 6, 2020.

Published on December 12 2019