Review

The Abstract Qualities of Wear: Roberto Turnbull at Le Laboratoire

by Eric Valencia

Reading time

6 min

A more-or-less generic way of understanding and producing abstract painting nowadays is to see it as a kind of hypertext. As Laura Hoptman puts it, citing a conversation between Kerstin Brätsch and Amy Sillman, in her essay accompanying the exhibition The Forever Now (MoMA, 2014-2015): “An abstract gesture is not empty anymore but loaded with historical reference.”*1 In this particular condition, abstract painting and its criticism can easily become a kind of exercise in inferential statistics. That is, a statistical sampling of references that, combined strategically, aim to forecast a greater effect and a surplus value of meaning.

Within this context, the work of Roberto Turnbull seems to obey a different logic, albeit one that is no less rigorous. Turnnull’s work is rooted in a logic arising from a profound reflection on certain qualities of the second-hand objects that he regularly collects and has used repeatedly throughout his career. Based in this procedure, he’s evidently reluctant to make explicit references to the history of painting: rather, each of the decisions with which he saturates his paintings is subjected to a process of decoding, starting from the explicit or implied inclusion of these objects.

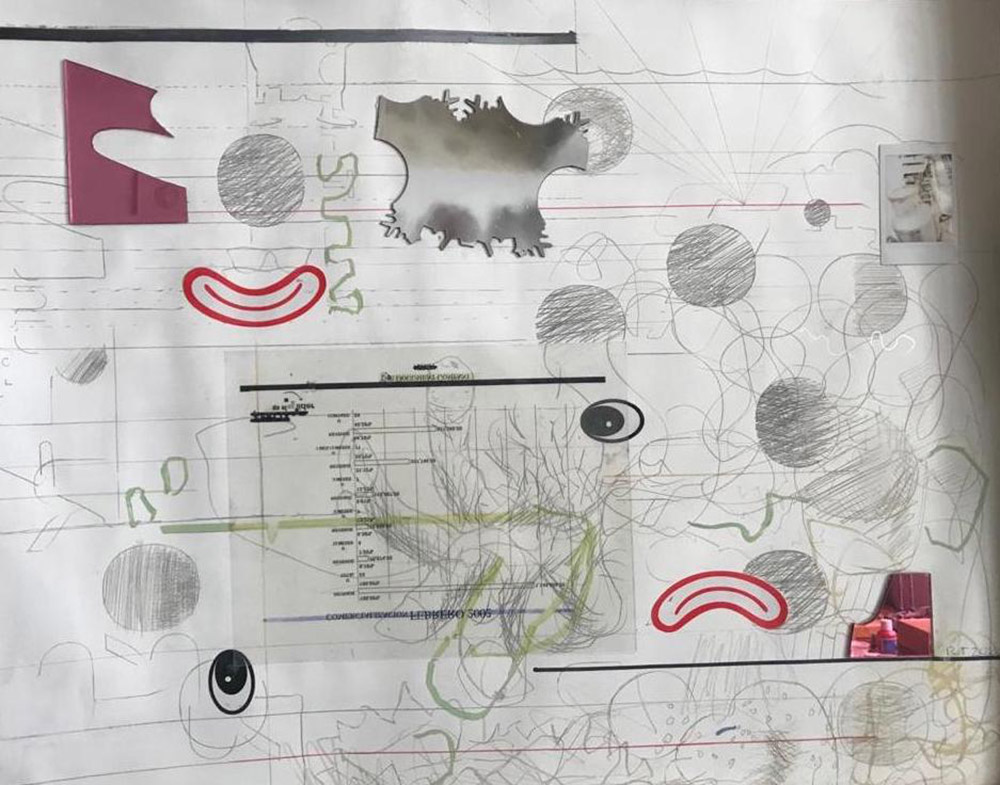

In the two series, Sin señal (“Without Signal”) and Nubes negras (“Black Clouds”), currently being presented at Le Laboratoire*2 and giving the exhibition its title, Turnbull once again utilizes found objects. We find them explicitly presented in the works Punta de plata (“Silver Tip”) 1, 2, and 3 in which he puts to use stickers of eyes and mouths, calculation sheets, graphs of obscure data, clippings of color swatches, and pieces of paper of different finishes. We also find patterns of lines made with templates.

In large-format paintings belonging to the series Sin señal, particularly in Selva (“Jungle”), Ojo - Sol (“Eye-Sun”), Conjunción (“Conjunction”), and Mono Verde (“Green Monkey”), we again see the use of these templates, only now using stencils (estarcidos)*3 and spray paints. The result consists of patterns of abstract shapes in generally phosphorescent colors, distributed across different parts. This process functions as a kind of transit between object and painting, as it requires the existence of the former at a certain moment, but without the need for it to remain in the final work. Another interesting quality of this method is that the resulting forms lose their referential capacity: the templates serve as molds, but their specific use has been worn out.

With this idea in mind, let’s take a look at the series Nubes negras. It’s made up of canvas frames with pasted-on sheets of paper, on which the artist had previously drawn stains of a washed-out black color. To achieve these stains, two methods were used: ink was applied directly to the paper (Nube negra 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5) or a printing process known as monotype was used, consisting of smearing paint—in this case acrylic—on a rigid material in order later to stamp it (Nube 6 and 7). On top of that, solid color areas were painted (Nube 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, and 7) or veiled (Nube 3).

During the exhibition’s opening tour*5, the artist noted that for these works he was inspired by the cloud paintings of the English romantic painter John Constable. It’s clear then that the black stains aren’t only clouds, but also have a direct reference to the history of painting. In an apparent contradiction, and making use of a refined sense of humor, Turnbull added: “I tried to make them my own [clouds], though they later ended up looking like cockroaches or trodden animals. But the initial intention was to make clouds.”

When compared with the above-mentioned estarcido technique, this statement allows us to intuit a sequence in his artistic process. First, an object serves as a “model” and then disappears (template). Second, a flow runs through it (paint, in this case spray paint). Third, an impression of that flow remains on the canvas, referring to the shape of the “model” but without imitating it (patterns of diffuse shapes). We can call the result of this process found shape.

To the extent that the presence of the object serving as “model” doesn’t remain in the final work, we can include, in addition to the templates, all those visual stimuli that the artist has collected in his memory. Turnbull, by assimilating all those shapes he sees, makes himself into a kind of template.

Let’s go back to the works in the Nubes Negras series in order to update the sequence described above: first, John Constable’s cloud paintings are seen by the artist and held in his memory (template); second, a flow (an artist-memory-sense of humor-painting flow) paints them; third, the resulting shapes refer to the remembered image (painted clouds), but without imitating them (it doesn’t matter that ultimately they look like cockroaches or trodden animals).

Under this analysis, the found shapes that Turnbull paints in his works lose all hierarchy and all status: it doesn’t matter whether they come from a work seen in a museum, from an anatomical diagram, from a food stand ad, or from a swatch of color. What one has to look for in his work aren’t scholarly clues to the history of painting, but the rigor with which he submits himself to the methodology he’s produced over the years.

The shapes that appear in his works aren’t figurative reproductions of the objects he collects, but the sum of transformations that they acquired when adrift: as if, by submitting these images to the tensions of his nervous system, he discovered—to be able to paint them—the abstract qualities of wear.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

*1 Hoptman, L., (2014), The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World, New York: Museum of Modern Art.

*2 This text was written based on the exhibition’s original installation. The works displayed at Le Laboratoire may change depending on the date of visit. All the works referred to here can be consulted on the gallery’s webpage at http://lelaboratoire.mx/wp/202006-sinsenal/

*3 Estarcido is a technique that consists of drawing lines or applying paint on any kind of support through a rigid sheet with holes of different shapes.

*4 lelaboratoire [@galerialelaboratoire]. (2020, September 15) Sin señal / Nubes negras, Roberto TURNBULL [IGTV]. Accessed at https://www.instagram.com/tv/CFK_deqjybP/

Published on November 6 2020