Review

Stalking. 'Watch Yourself' by Robin F. Williams at Morán Morán

by Mariana Paniagua

Reading time

5 min

I entered the room, drawn in by the green radiating from the painting from which the exhibition takes its name. I hadn't yet noticed that it was different from the other six works on display. The woman depicted in this artwork, painted as if refracting all the colors of her skin, almost looks directly at me from above while smoking – at least it seemed to me – with confidence. I'm struck by the contrast between her body language and that of the woman in the adjacent painting: Beyond the Curtain, who peeks fearfully into the darkness from her warm and secure room, completely unaware of my presence. Both seem framed, staged, and filmed, covered by the static frequencies of 1980s color televisions.

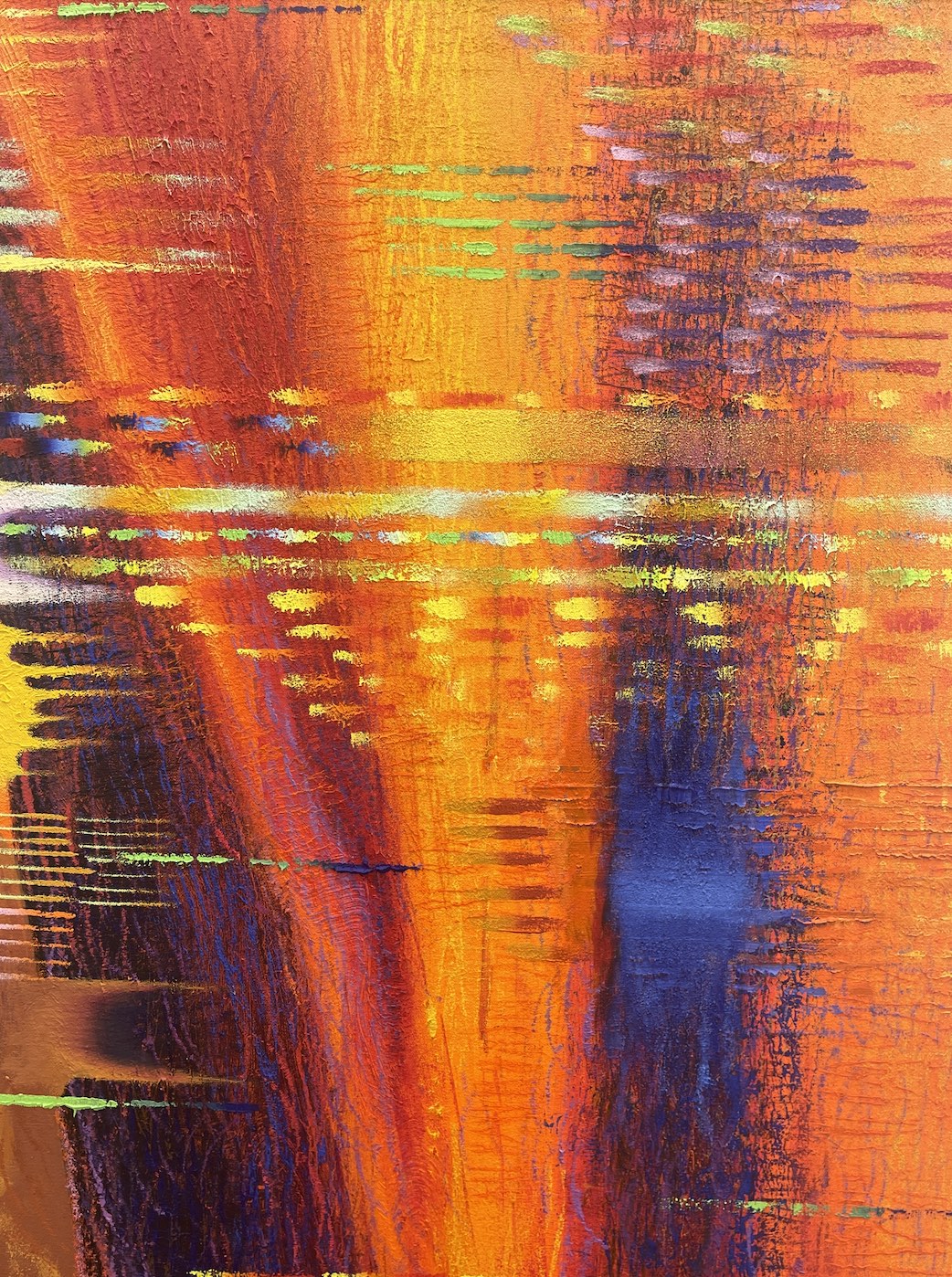

The seven paintings depict scenes containing women illuminated with precision in terms of color, translated into the simulation of an overexposure of film. What first captures my eye also captures my touch: despite simulating images appearing on a screen, I can witness color in its most mineralized form. Iridescent, yet corporeal.

The figures are ensnared within a framework of electronic or digital appearance, which at first glance appears to be made of weightless photons, hinting at the virtuality of the protagonists who, nevertheless, have a body: thick strokes of dry oil paint appear without dilution or smoothness. The presence of oil in the paint is only evoked by the trace of fluid brushstrokes in the works, but the body of dust from the pigments is more prevalent.

A painting that merely resembles a digital image would suffice for the retina; however, there are several layers of representation, as well as densities of matter.

The series' common thread is the stereotype of the woman stalked in slasher films*1, immersed in an erotic tension before death, the vulnerable female body in imminent danger, observed by us, the spectators. Williams approaches the term final girl*2 to explore the role of female characters in these films, who manage to escape or defeat the killer after surviving terrible violence.

She also envisions different facets of character archetypes like the virgin, the prom queen, and the cheerleader to refer to some expected traits of female behavior represented in American pop culture and questions to what extent they are conditioned by moral judgment. In the plot of a horror film, the question must be answered: "Which women deserve to save their lives at the end of the movie?"

The women in the paintings don't look back at us. They don't know someone is looking at them, but they sense being stalked. My own gaze becomes foreign to me: it's now in the place of the predator's gaze. It's not just the terrified expressions of the characters, the hiding, or their embodiment of horror movie victims that make me feel like I'm preying on them, but also their theatricality and their immersion in a network of material pixels. Being in the fiction of the screen.

In addition to being displayed on the screen – due to the cinematic reference and the sign of the gridded static of the television – they are in front of the gaze in function of the screen, where the image confirms itself and is unequivocally displayed. The gaze is subject to a one-sided reading of the image. In painting, in what ways is it possible to diminish agency from the screen-gaze and give back a little to the gaze of a body that observes?

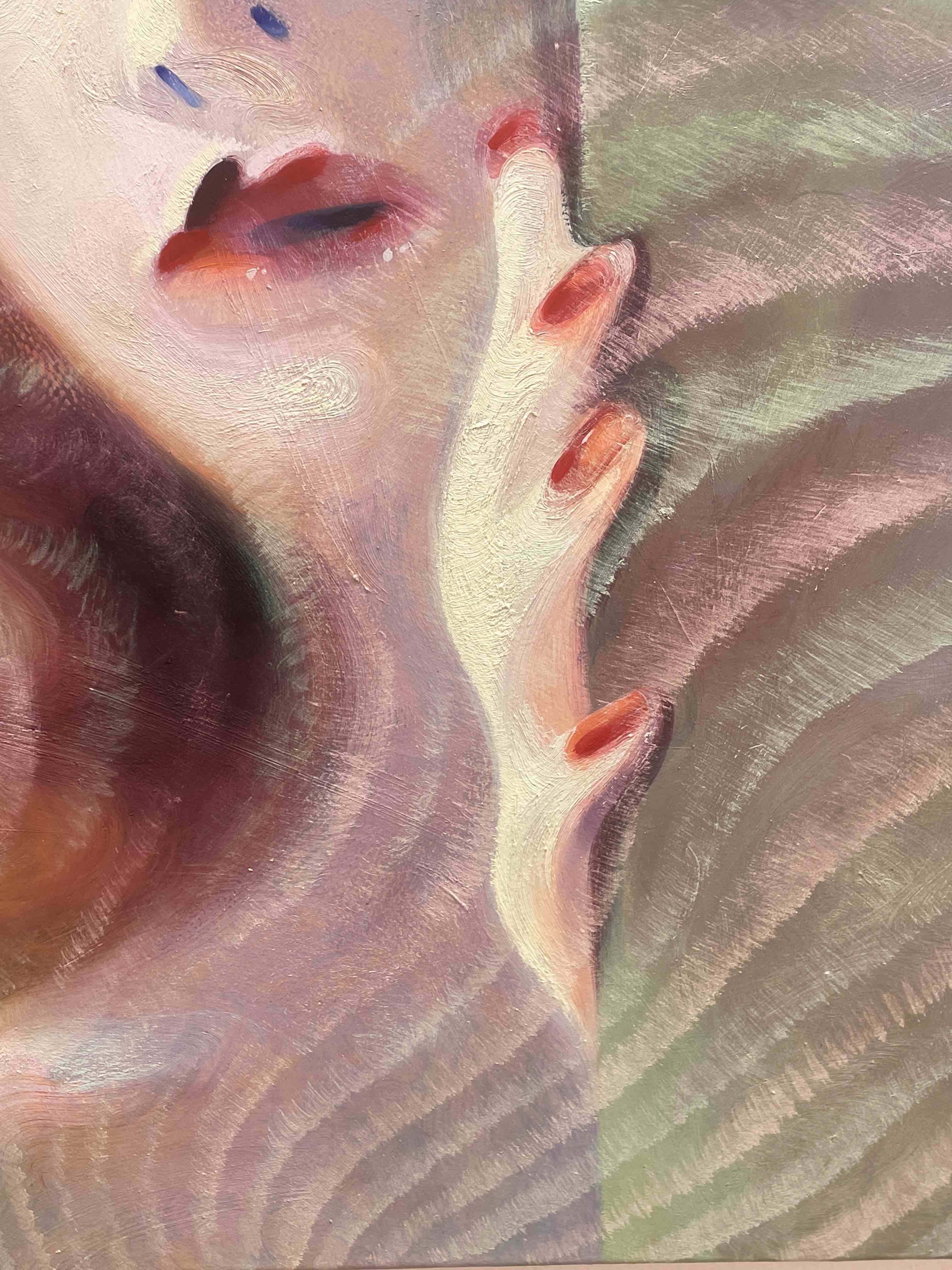

In Locker Room Heretic, there is a much more virginal character, almost like an apparition that barely materializes into extremely pale skin and a cerulean blue environment. In that ethereal space, her hand – with red nail polish and much more flesh in the fingers than in the rest of her body – clings to the edge of a locker sheet that’s barely suggested. That hand, so luminous that it gives the sensation of being grounded in a layer of decay*3, more real than the rest of her body, manages to escape the virtual space by surpassing the translucent waves that suggest a muted sound: a vibration.

One thing that excited me about Robin F. Williams is that she shows several of her processes on TikTok, creating space in the pause of each layer of her paintings, revealing the structure of her material bodies and the movements of her own body behind the resulting image, reversing the staging montage. I wonder how it would be possible to support this disassembly – and with it, the possibility that the gaze does not exhaust itself on the surface or is conditioned by it – when the painting is already finished, to crack the sensationalism of slasher images' verticality.

Between the cinematic image and the pictorial image lies the passage of time. In slashers, there is survival, fleeing outward and forward: linearity. Whereas painting leans more towards a temporal non-linearity, where the moment of escape never arrives, the oxidation of matter on the support is sustained at an almost imperceptible pace.

In the painting Slumber Party Martyrs, virtuality is not imposed; the figures seem sculpted, they unfold freely in the disconfiguration of the planes. Color dramatizes, as did the luminism of the Baroque, with the weight of its intensity. The reflection of the fire is an orange pupil emerging from a dark ultramarine field, a glimmer in a black mirror.

Translated to English by Sebastián Antón-Ojeda

*1: Subgenre of horror cinema that depicts the pursuit and murder of young people by a psychopath.

*2: Coined by Carol J. Clover in Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film, published by Princeton University Press in 1992.

*3: A mixture of medium and oil with white lead pigment used in grisaille painting to provide volume and luminosity to specific areas of a work.

Published on October 6 2023