Interview

Taking Your Eye Out and Putting It Back In, Listening: Interview with Angélica Piedrahita

by Sandra Sánchez

Reading time

9 min

In addition to being a multimedia artist concerned with memory-constructing technological devices, the human and non-human rhythms surrounding everyday life, and the production of experiences and images, Angélica Piedrahita gives classes on the Static and Moving Image, Multimedia, New Media, as well as Video and Sound Art, at the University of Monterrey (UDEM). In this interview, she tells us about her transits between both of these practices, together with her vocation for the experimental and immersive.

SS: In your artistic practice there’s an interest in the production of images and visualities that construct narratives and cultural stereotypes. How do you work on that from within the classroom?

AP: I don’t work with the term stereotype; I instead use cultural interface, which comes from Lev Manovich. For him, the book is a cultural interface, and so is the web browser’s scroll; the immersion and foreshortening in the Sistine Chapel have to do with cultural interfaces. He does a kind of genealogy of the look, in the same vein as Régis Debray or Jonathan Crary’s Techniques of the Observer, which has to do with the ways in which devices cause certain ideologies to be transformed. Perhaps you could say it’s a kind of technological determinism; they go hand-in-hand. All politicians have Instagram, Twitter, Tik Tok; the image makes a demand for us to enter the public and private spheres. Rather than stereotypes, it’s about understanding the visual prostheses that we all have. In the case of the students, it’s to teach them to disassemble and to reassemble those prostheses, to hack them, to redesign them, and to be conscious of where one is at the moment.

SS: In 2018, at the Encuentro Javeriano de Arte y Creatividad, you presented Estéreo Nostalgias y Telepaseos Por Un Lugar En El Caribe (“Stereo Nostalgia and Telematic Rides Along the Caribbean”). The different pieces are the result of an investigation into the 1913 commission, made by the North American stereoscopic production company Underwood & Underwood to Horace Dade Ashton, with the aim of creating a stereoscopic tour of Barranquilla, Colombia, an important port at the time.

Using a mobile display device, you presented stereoscopic images to the current inhabitants of Barranquilla and asked them about the places shown there. I’m interested in the tension between image, archive, and narration. Share with us how you formed a constellation out of these three edges, as well as how you transmit to your students the possibilities of working from within that framework.

AP: Estéreo Nostalgias is a project that took a long time; it began in 2015 with various exercises that have been transformed into many things, including currently a book. I started working on the project with undergraduate students; we arrived at a very interesting place, which was to propose that History itself is made from images, files, and narratives. That’s why the History of Art becomes so important in the narration of our passage through Earth. We remember times in the world from their images and from what they produce.

In Estéreo Nostalgias it caused me a lot of trouble that many images had a markedly colonial tint. For example, “washing day” is a super-common image in many countries, such as the Philippines, Cuba, Peru. They’re women washing white clothes in a river, in a 100% picturesque and folk-traditionalist composition. The idea was to show the North American population that in other countries there was cleanliness and a structure in which they could feel comfortable. When I took those images to the place where they were photographed, the narration ended up being something else. They didn’t really care about the colonial discourse; for them it was important to take into account the historical changes that had occurred. It’s a question of memory and history. That got me thinking that the stock footage was loose and without narration.

In the book, the project’s title has changed; there it’s called ESTÉREO NOSTALGIAS: inmersión, estereoscopía y educación visual (“Stereo Nostalgia: Immersion, Stereoscopy, and Visual Education”). The publication asks about the expansion of the image in terms of discursive dissemination: the way in which certain territories and media began to relate to each other. There are portions of video, portions of the piece and of text. There’ll be an official launch in September at the Treceavo Encuentro de Fotografía.

SS: In Ejercicio para una posible visualización de las propiedades cuánticas de la luz (“Exercise for a possible visualization of the quantum properties of light”) you mention that “in quantum phenomena the influence of the observer is unavoidable, since an intermediate observation for determining which of the slits the particle passed through changes the results of the experiment.” From there, tell us whether or not you think that scientific observation is similar to artistic observation.

AP: Both Donna Haraway and Bruno Latour always emphasize taking into account the particularity of the observing subject. Both speak to the scientist in order to make them understand their subjective position, why they’re looking in the way they do. In classical physics and mathematics the look is immobile because it’s verifiable; it’s something very determined and built-on from there. When deconstructing these structures it’s important to ask ourselves, on the one hand, what happens with the quantum and, on the other, what happens when physics is studied from the perspective of an indigenous cosmogony.

What about other cultures? When the Chinese began using a keyboard that worked the same as the western one, they had to do a whole set of mathematical, physical, chemical processes and relations so that these subjective forms of language could go though. In the case of the arts, it’s a super-Lacanian wave: you have to deconstruct the eye. For its part, quantum science destabilized science’s belief system. Both are painstaking processes of taking the eye out and putting it back in, leaving you on top of principles of uncertainty.

I worked with a physicist on Ejercicio para una posible visualización… In our conversations I didn’t feel that I was talking with a scientist: her level of abstraction and of understanding materialities was close to metaphysics and the arts. This was even though at the time of representation, she did enter measurements, of what was supposed to be happening.

SS: In Sonría, sin pruebas no hay culpables (“Smile, without proof there is no one to blame”) you printed out a series of fake cameras on lenticular sheets. The effect is that each camera seems to follow the viewer by changing position according to their point of view. From there, do you think observation has spilled over from the animate to the inanimate?

AP: In facial recognition, computers see black and white, the separation is what makes them recognize if it’s you or me or who’s who. There’s a lot of error between black, white, and the gradient comprising the volume. In the end, what you’re teaching the machine is how to draw. In painting and drawing you teach how to blur; with the machine you have to teach it what’s what.

What I find interesting about Sonría, sin pruebas… is that they’re fake, toy pieces, using an LED. The camera may not be recording, but if it’s present we’ll behave in a particular way. That’s the control we exert over ourselves. An image isn’t just an image; I begin to see and to read others based on how they look.

SS: Finally, based on your work with your students, how do you think that visuality regimes have changed from your time as a student to the present? What do you imagine are the challenges for continuing to produce images without their being completely captured by advertising logic?

AP: For decades, there’s been a very strong change in the status of images, even that of objects. Right now I’m working on expanding the notion that an image isn’t just a visual element. If we understand that an image can come as much from an experience as from a thought or a sound, we’re a tiny step beyond advertising logics.

Beginning in 2019, a friend and I started doing workshops on listening to hearts with a stethoscope. We recorded the sounds of the attendees and made remixes. There was one session with kids; one of them didn’t know where his heart was and when we put the stethoscope on him we asked, “Where do you have your heart, child?” He was a very introverted and silent person. Another child, more extroverted, told us that it was everywhere, and, yes, indeed, we placed the stethoscope on his head and his heart was leaking out of his body. Between all of us we generate a cordiality, a harmony of hearts; it was a very emotional thing just to listen to the heart of another.

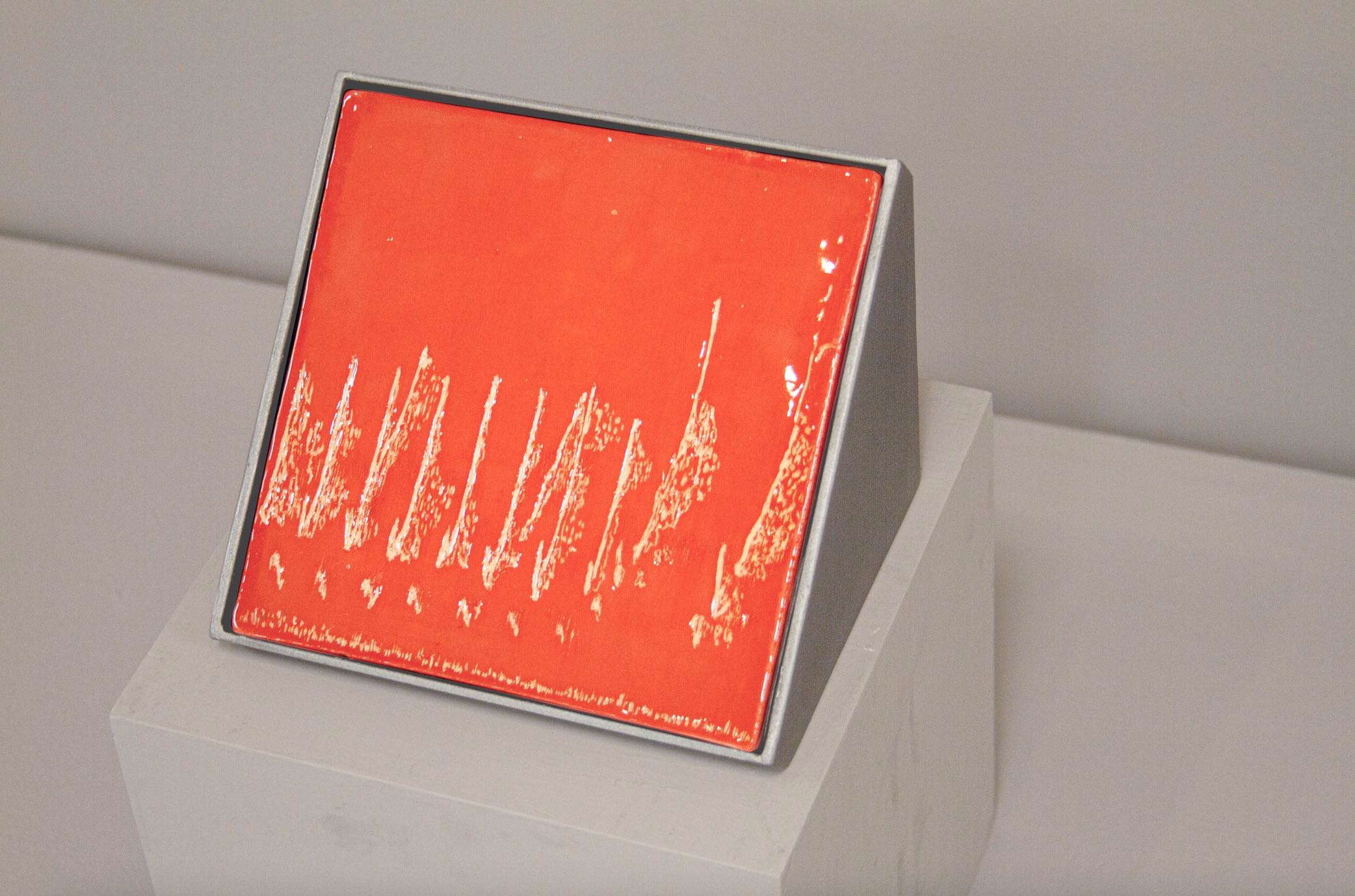

For years the heart has been represented with the “pum pum, pum pum.” We wondered at what point the treatment of the psyche moved from the heart to the head. Harvey [Williams Cushing] found the pituitary gland; everything that passed to the brain and the heart was devoid of emotionality. We had to stop the project because of the pandemic. Later, isolated from people, I ended up listening to birds and recording them. Right now I’m working on the ceramic translation of songs belonging to some of the birds in the city.

Translated to English by Byron Davies.

You can enjoy Angélica Piedrahita’s work at https://lapiedrahita.com/ or, if you're in Monterrey, you can visit her exhbition Biopoéticas at CEIIDA until August 31st, 2021.

Cover picture: Angélica Piedrahita and her students in a sighting workshop. Photo: Andrea Juárez Neyra.

Published on July 31 2021