Review

Potential Imaginaries of Neoprehistory: Ernesto Solana

by Nicolás Barraza

Reading time

4 min

A month ago I was encouraged to visit the exhibition Institute of Neoprehistory: Chapter II by Ernesto Solana, at the Guachimontones archaeological site in Teuchitlán, Jalisco. I was not familiar with the place, and I went to it with the same expectation or attitude with which one might go to Mexico City’s Anthropology Museum, or to any of the impressive and numerous ruins throughout the country.

The site is used to emulate an institutional setting, which is reaffirmed through its being exhibited alongside original pre-hispanic artifacts and archaeological archives from the Weigand family. Who determines what was true and what is true, and via what mechanisms?*1 On one side we find collages of anthropomorphic and intersexual beings, all by Solana of course. On another side we have a didactic installation that tests our memory for reconstructing a vase found at the Guachimontones site, an installation resembling those at the Great Museum of the Mayan World in Mérida, or anything at UNAM’s Universum.

Nevertheless, it is at this meeting point that the artist (re)imagines and (re)formulates an apprehended past: perhaps with the aim of conceiving of a different future, or of bestowing new meaning on what we already know. For me, this is where he explores the tension-interaction between reality and fiction. The project seeks to be an exercise in the (re)interpretation and (re)appropriation of vestiges related to the communities that inhabited western Mexico, specifically the tradition of Teuchitlán, which worshipped Ehécatl, the wind god, in the ceremonial center located next to the “instituto.”

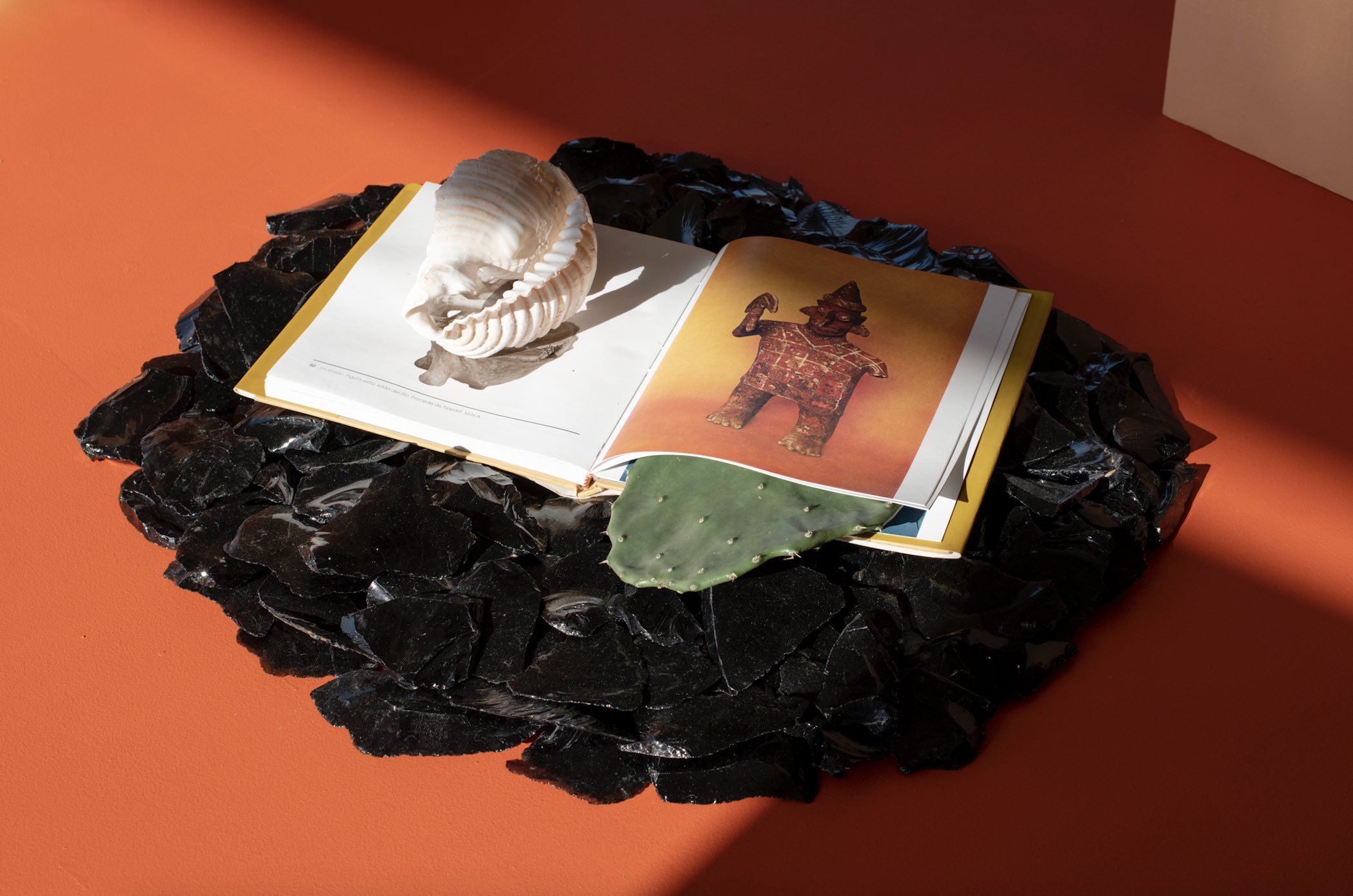

The exhibition consists of sculptural installations in various materials, such as volcanic rock, feathers, winged calabash, textiles, and obsidian, to name just a few.

Also presented are Estudios arqueológicos del Guachimontón (Phil Weigand) and Estudios de saqueo del occidente de México (Memorias extirpadas), two display cases showing memorabilia, books, photos, drawings, and watercolors by the archaeologist Adela Breton dating from 1880, as well as pre-hispanic artifacts, feathers, and animal skulls. In two-dimensional format, the artist presents various photographic collages, as well as an artistic intervention within the archaeological site. Some objects and photographs were loaned by the American Museum of Natural History in New York, the Bristol Museum & Art Gallery, the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), and the Colegio de Michoacán.

El Instituto de la neoprehistoria molds a (fragmented) landscape of what we were or could have been. It made me think of the copying and looting of Latin America by other countries. It left me reflecting on not only the transitory nature of History—referring to the work of Cynthia Gutiérrez, who (re)articulates historial elements and highlights the impossibility of generating precise memories*2—but also on the way in which History has been written, edited, disseminated, and represented in textbooks, schools, films, political discourses, etc. It reminded me of the book The Broken Spears (La visión de los vencidos), which appeared in 1959, four centuries after the arrival of the Spanish in Mexico, and which for the first time offered a different vision of the conquest, as it is composed of a series of texts narrating the image that the Indians of Tlatelolco, Texcoco, Tlaxcala, Chalco, and Tenochtitlán had of the occupation.

The fleeting nature of human beings and their stories is as malleable as fiction itself. Of what are we absolutely certain? I believe of nothing. Solana’s own project can confirm this by proposing a different future, taking on objects and images with new meanings. The artist presents a new reality that certainly left me thinking about our ability to mold and (re)write our own past, our successes and our errors, our pain and our impotence, our past and future relationships. It lies in our hands to build the path we decide to follow, relying on the past—certainly—but above all (re)appropriating it. I conclude with a quotation from Valeria Mata’s curatorial text about the exhibition, but perhaps also about History and life: “Fiction is not the creation of an imaginary universe opposed to the real one. It is a change in ways of presenting the sensible, an alteration of interpretations, a new proposal for relationships between appearance and reality.”

Institute of Neoprehistory: Chapter II can be visited at the Centro Interpretativo Guachimontones “Phil Weigand” until March 2022. The first iteration of the project was presented at the Guadalajara headquarters of guadalajara90210 earlier this year.

— Nicolás Barraza

Translated to English by Byron Davies.

*1: Curatorial text for the exhibition by Valeria Mata.

*2: Artist statement by Cynthia Gutiérrez.

Published on December 28 2021