Essay

For the Night is Dark and Full of Terrors: Isolation, Delirium, and Exteriority

by Christian Camacho

Reading time

11 min

Dogs waking in the middle of the night,

to scream mindlessly for several minutes

and later observing, “I do not prefer it.”

1:01 A.M. · May 26, 2020 9 Retweets 42 Likes

Dogs staring at a wall,

and then after a sufficient time,

staring at another wall.

4:15 P.M. · May 14, 2020 26 Retweets 68 Likes

Dogs hacking into your video conference

just to say hello.

4:18 P.M. · May 8, 2020 26 Retweets 62 Likes

Dogs getting shitfaced,

and harassing anyone

unfortunate enough to be on the internet.

6:03 P.M. · April 29, 2020 6 Retweets 32 Likes

A dog howled with laughter in the dark.

“I’m scared,” said a child.

“Scared of what?” asked the mother.

“Of my dog.”

“But you don’t have a dog.”

“Yes I do.”

But then the little child also laughed while crying,

mingling tears of laughter and fright.

- Clarice Lispector, Where Were You at Night (in The Complete Stories, trans. Katrina Dodson)

One of the things I want to talk about today is an idea I came across while trying to give shape to different literatures about the night, and which has never left me indifferent: the image of the night as being lucky enough to have within it another, smaller night, a type of parlor, corner, or cavern, and that it’s there that the night finds you, when it finds you alone.

At this time, as this year runs its course, this strange operation is already familiar to us; thinking of a kind of world of diffuse limits, of a shadow lit by apparatuses—the night as we produce it today—whose folds have to bend all at once on the dimension of a new opaque and tiny space, inhabited by the uncomfortable geometry of our own retreat. The body-mind in involuntary rest, its gaze suspended in the central vortex of a transparent cube, made from the air of eight hours prior and a touch of claustrophobia.

In this text, I’m interested in developing certain considerations about what thinking and being mean for the imagination in these abrupt, other conditions, which have been drastically delimited by diffuse contact with those who surround us and question us, and by the permanent vertigo of an invisibly transformed exterior.

We open and close our eyes with certain pauses midway. An extravagant form of labor in these circumstances. Inside our buildings, the energy generated by our work is reconnected to another type of circuit. Something unexpected arises: nostalgia for the once-illuminated contribution in the nexus of the socialized space; despite its difficulties, a use of our time and energy that is always visible and evident, diurnal even when nocturnal, populated by people and by necessary exchanges. The old day that leads to night; or the working day.

Inside, at present, new jobs awaken, new unexpected tasks. Jobs that, like our night, have gone from the vast to the minute and particular: the job of turning on the light, the job of turning off the screen, the job of closing our eyes, the job of opening them.

Our inner system is reconnected to a dimension by several degrees more modest, to a withdrawal and compression that, without surprise, densify the inside and make it present, prolonging it. The transmission of the presence of the world to the interior, constructed environment has a strange consequence. The exterior is most likely a still-dynamic and complex place, but right now it has not only withdrawn, but is also populated by darker and more invisible exchanges. And in the right dimension of virulence, not only invisible, but also ominous in our battle against all the uncertainties of life and death.

One can ignore all this and claim that the transformation of the world can be seen with the naked eye, as if one could watch all one’s futures indefinitely postponed or one’s conditions suspended. In the end one can claim that the exterior has not been transformed by the interior, or vice versa. Faced with this possibility, I wish to recall a story perhaps known to several.

In the “History of the Necronomicon,” by the infamous H.P. Lovecraft, we have narrated to us the life of Abdul Alhaẓred, the “mad poet of Sanaá, in Yemen, who is said to have flourished during the period of the Ommiade caliphs, circa 700 A.D.” The book mentions his travels through the ruins of Babylon, the subterranean world of Memphis, and the Roba El Khaliyeh or the “Empty Space” of the djinns. A story of strange past adorations in solitude that curiously culminates in disturbing violence: debtor of extremely old and extraterrestrial deities, the poet is slaughtered by an invisible demon in broad daylight, in front of the frightened eyes of the inhabitants of Damascus.

One of the things that most interests me about this story is that Alhaẓred was devoured in a public place by an entity that persecuted him from beyond time and space, and yet nobody could see it. The blasphemy of the insane poet of Yemen was to come into contact with the exterior, with what is outside everything we can perceive and imagine. In the myths of Cthulhu, the outer spheres are places where he has spent all eternity writhing in that which is indifferent to time and matter, that which is not alive, but also cannot die, and is known to be in this condition.

I’m going to skip the comparison of these entities with the current virus. What I most want to pursue is the imagination in which the exteriority of the dynamics of the world has been inhabited by something invisible of whose scope we are ignorant. Does the exterior against which we raise barriers and distances reach the door? Perhaps the door is a coefficient of ours, perhaps we have also been attacked by a bad equation, a type of Ballardian terror in which the internal constructed environment is redistributed to us arithmetically: myself multiplied by four chairs, my forearm between my eyelid rendered into window blinds a million times.

This delirium should not be confused with an inability or a refusal to rationalize and respond to health alerts, nor with our deepest desire to empathize with and care for others. Oh, of course our ability to rave should not be confused with that of acting reasonably and lovingly! In part, this is what most dizzyingly mobilizes us to pay attention to the body-mind in crisis: its ability to confuse and merge its desirable and undesirable futures.

Fear of the exterior is made from the unknown, from the uncertainty and a high possibility that the volatility is more than we can bear. This pendulum that travels between the place where we are and between all the coordinates that we have put on pause, in oblivion or in the past, is also a source of strange duplication:

The confusion between diurnal and nocturnal signs gives way to a “we” that cannot help but get a little out of synch. Someone is slightly late. Someone simply won’t arrive in the near future. Someone’s already here. In the practice of insomnia, we go down and up the stairs in the earliest morning; we go fast because something is following us. Having dinner, the light goes out, and the night proceeds up to the diffuse rectangle of the laptop, which is the only non-darkness left. Or perhaps we turn off all the lights because this minimal night is actually all that we can bear. At 3 A.M. the electricity returns. We stare at the entrance and are sure that as the lights went down throughout the neighborhood, the exterior advanced toward our door. It’s been ringing the bell all night, but now it will finally sound, and what are we to do?

Although I should have used all the energy surpluses of this time in the distribution of my forces, in my physical rehabilitation or in the prolongation of my causes, the truth is that I have only used them to terrorize myself. There’s also something I owe to that terror, that my imagination owes to that terror, and that, as I always suspect, has to do with art.

Recently, in bringing to a close our online course with my students, we again went over My Father’s Suitcase by Orhan Pamuk. Broadly speaking, the text tells us why some writers write, advancing the archetype of an author who isolates himself in a room in order to work, partly because it’s what they wish and partly because they have no choice. The idea of aiming to be an isolated artist in a room resonates with many obvious and immediate issues. It should not be forgotten that in this schema, both artist and room are proverbial. Nevertheless, an idea of Pamuk’s that stands out concerns the kind of disposition that art’s imagination can bestow on us, allowing us to spend days in solitude (whether we are alone or not) and how that idea, somehow, has to do with how much has been scarified in order to come into contact with art, beyond this or that person’s wish to flee from society in order to, just like Alhaẓred, dedicate their isolation to making contact with ancient deities: as could be read in Gilbert and George’s To Be With Art Is All We Ask. In any case, we must never forget that this moment, though capable of arousing very important artistic powers, in reality is often also a disregard for the world, creating for art a profoundly fraught responsibility, one through which all the outstanding wounds, which we witness in solitude, seize us in common. Pamuk is not naive in this regard, and I think it’s very much worth leaving the matter up for discussion.

In fact, it’s not difficult to say how much of this issue has progressed due to our confinement. Much more than perpetual contact with the sacred, in our isolation we have chosen this or that form of distant earthly participation. Also, it must be said, without knowing what kind of sacrifice this decision implies. The dense invisibility of the exterior stuns and frightens; the night-day of the built interior becomes a fertile place for the breach of promises.

What to expect from this gradual change that looks more and more like the eve of an indefinite delay?

In the anteroom of a moment that never seems to arrive, we pay attention to certain things that have appeared among life as it has always been, but that at the same time make it other, knowing that it has always been other. The time spent observing this difference will be able to take us, if we wish, to a new place:

It isn’t necessary that you leave home. Sit at your desk and listen. Don’t even listen, just wait. Don’t wait, be still and alone. The whole world will offer itself to you to be unmasked, it can do no other, it will write before you in ecstasy.

— Franz Kafka, Zürau Aphorism 109 (trans. Roberto Calasso)

We must remember that not only in the pandemic have we been challenged by the shadow of our own ideas in isolation. In fact, I have no trouble thinking about the current thick shadow inside the home; it’s nothing but the amplification of the strange vertigo that for years has been announced as product of living among cruel labors and between cruel communities that never find a fair start, nor a fair end. What a curious thing to think that we called the exterior normality.

Finally, I must say that I find profoundly disorganized any idea suggesting that the exchange between interior time and exterior time is at the disposal of others. Just as demonic entities can only enter the home after receiving permission, so terror becomes production only if it is voluntary. This strange idea shouldn’t surprise us: our contact with that other exterior is, as attested by the always-closed doors of buildings, a terror unqualified and ancient.

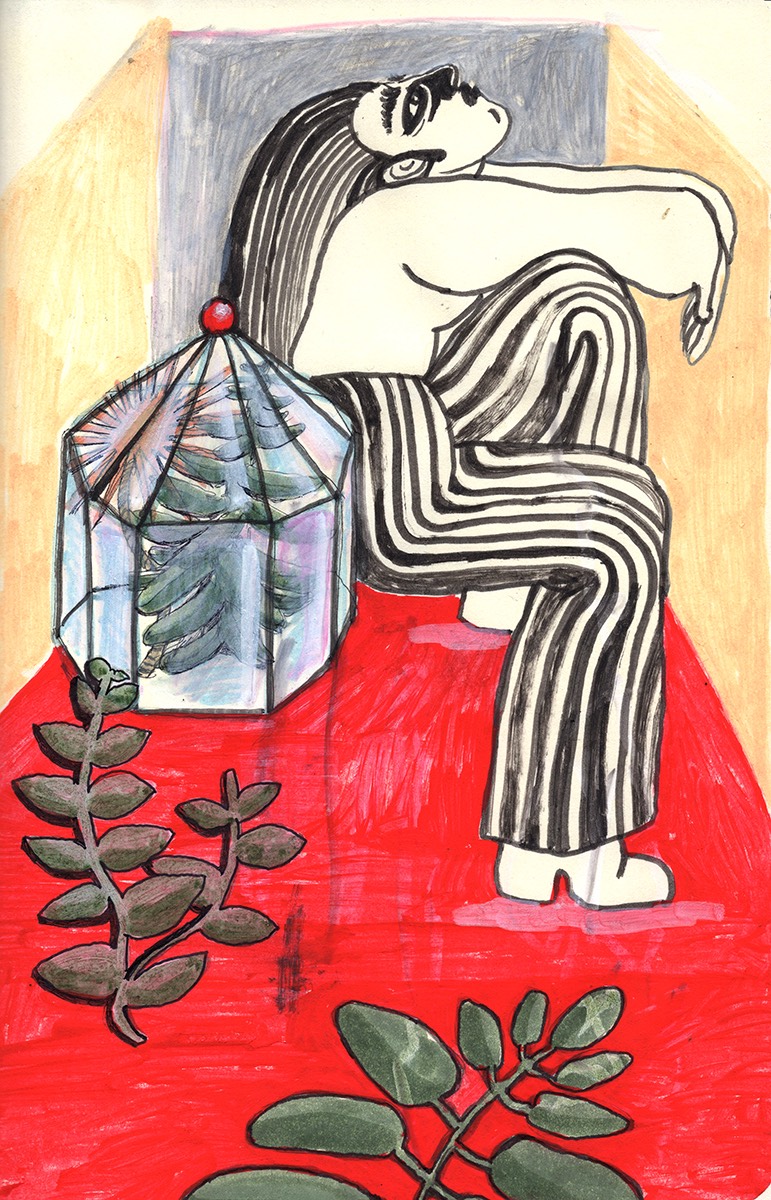

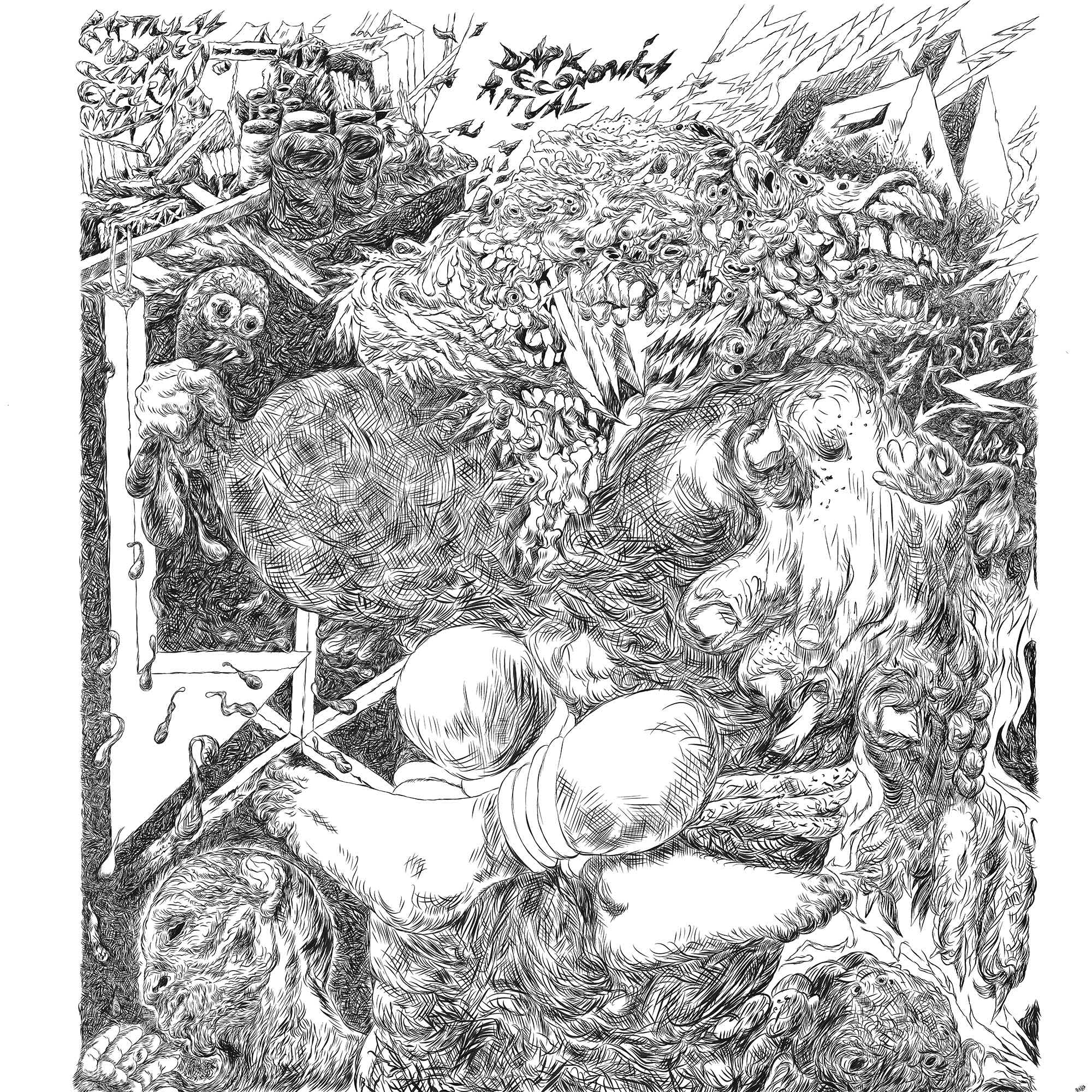

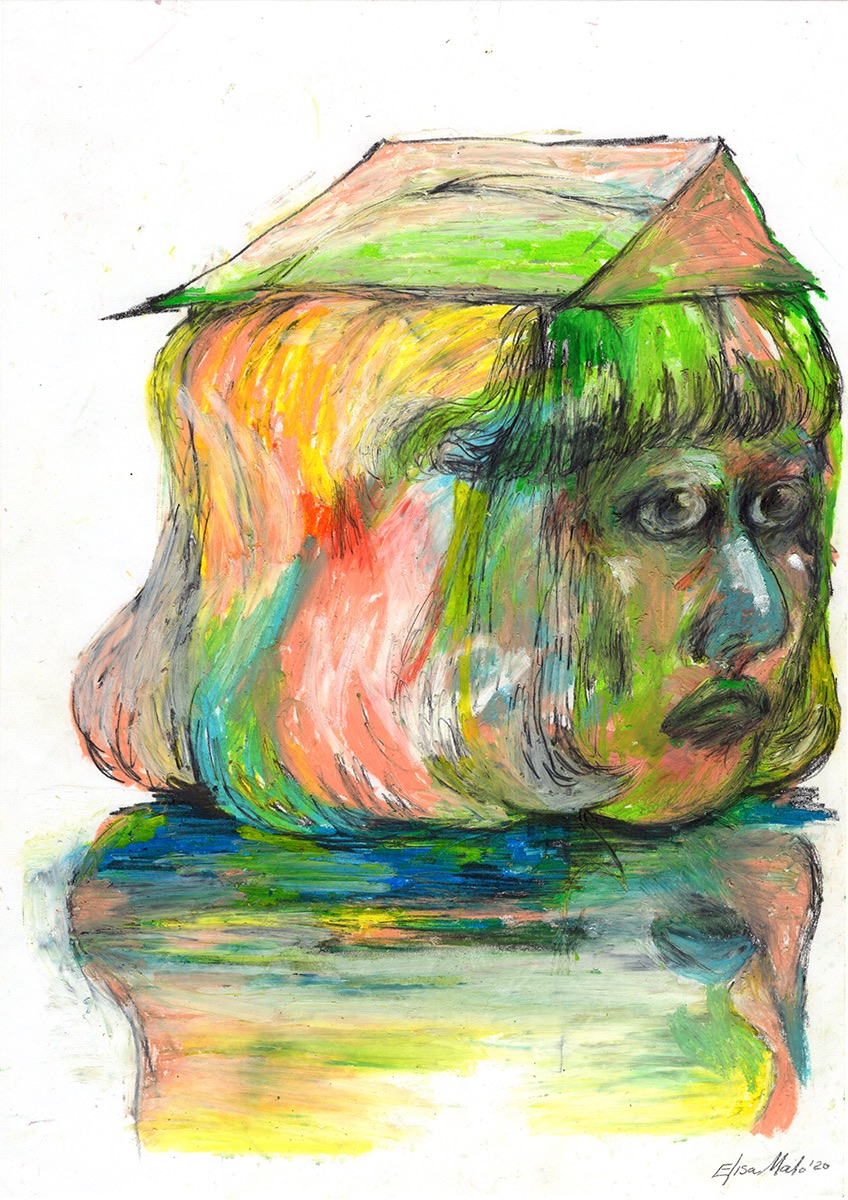

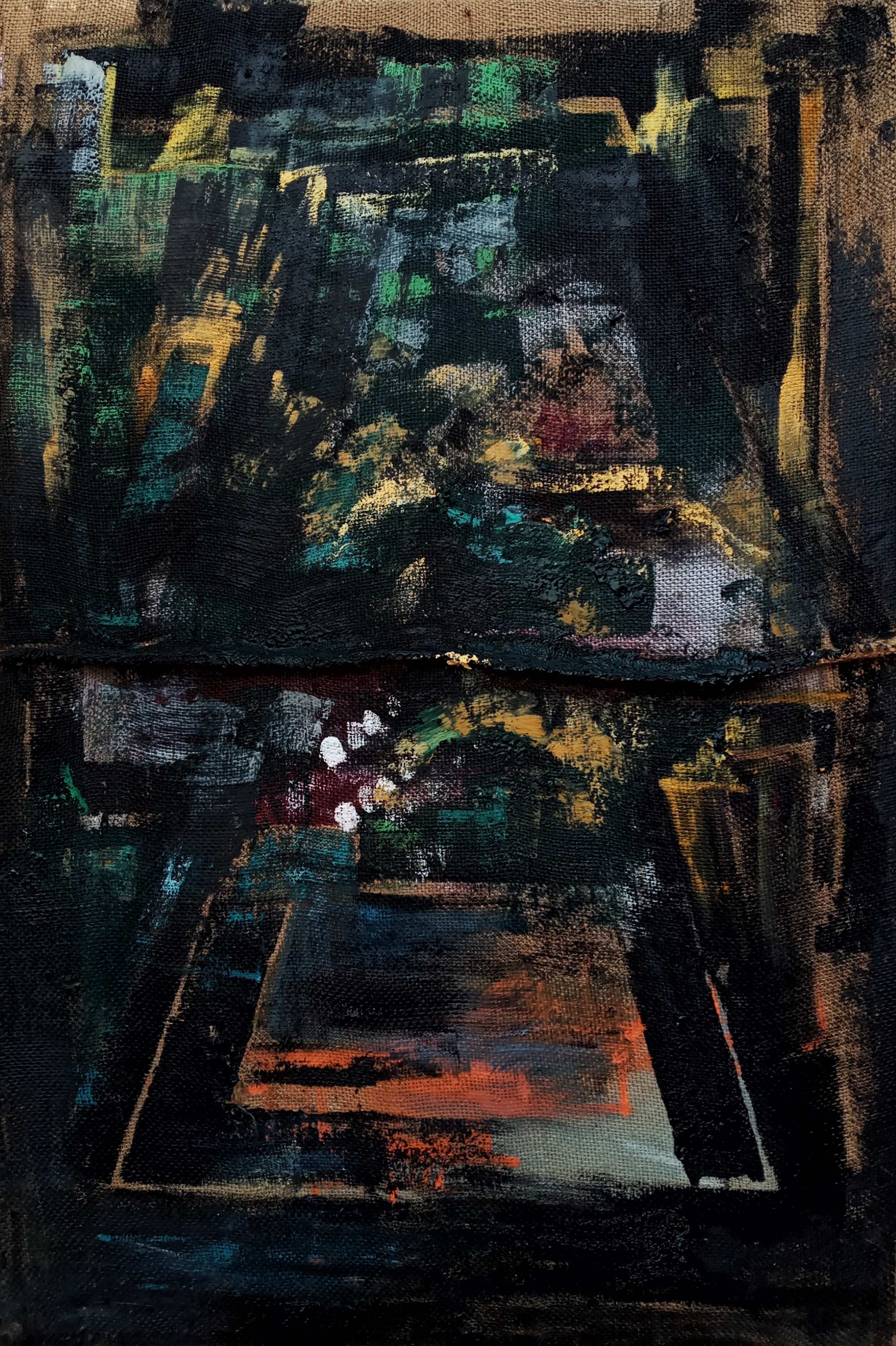

We deeply appreciate and thank the generosity and trust of the artists Luis Aduna, Alicia Ayanegui, Roberto Carrillo, Elisa Malo, Edgar Silva and Lucía Vidales as they join us, through their work, along this text.

Published on July 11 2020