Review

Thinking with the Fingertips: Antonia Alarcón at Servidor Local

by Lia Quezada

Reading time

4 min

The work of Antonia Alarcón is rooted in longing—raising one’s eyes and no longer finding the Andes—but also in anguish, particularly the anguish of solastalgia (the stress produced by environmental degradation and the sense of loss in the face of irreversible changes to the land). Two years ago, she presented Con mi dedo trazo el camino del agua [With My Finger I Trace the Path of Water] at the Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil, the result—or rather, the process—of a research project on the human and nonhuman species that cross the northern Mexican desert, ignoring the lines imposed by nation-states. I remember woven mats laid out on the floor, cushions, stones engraved with words; I remember how the reddish and purple tones of the embroideries evoked scars.

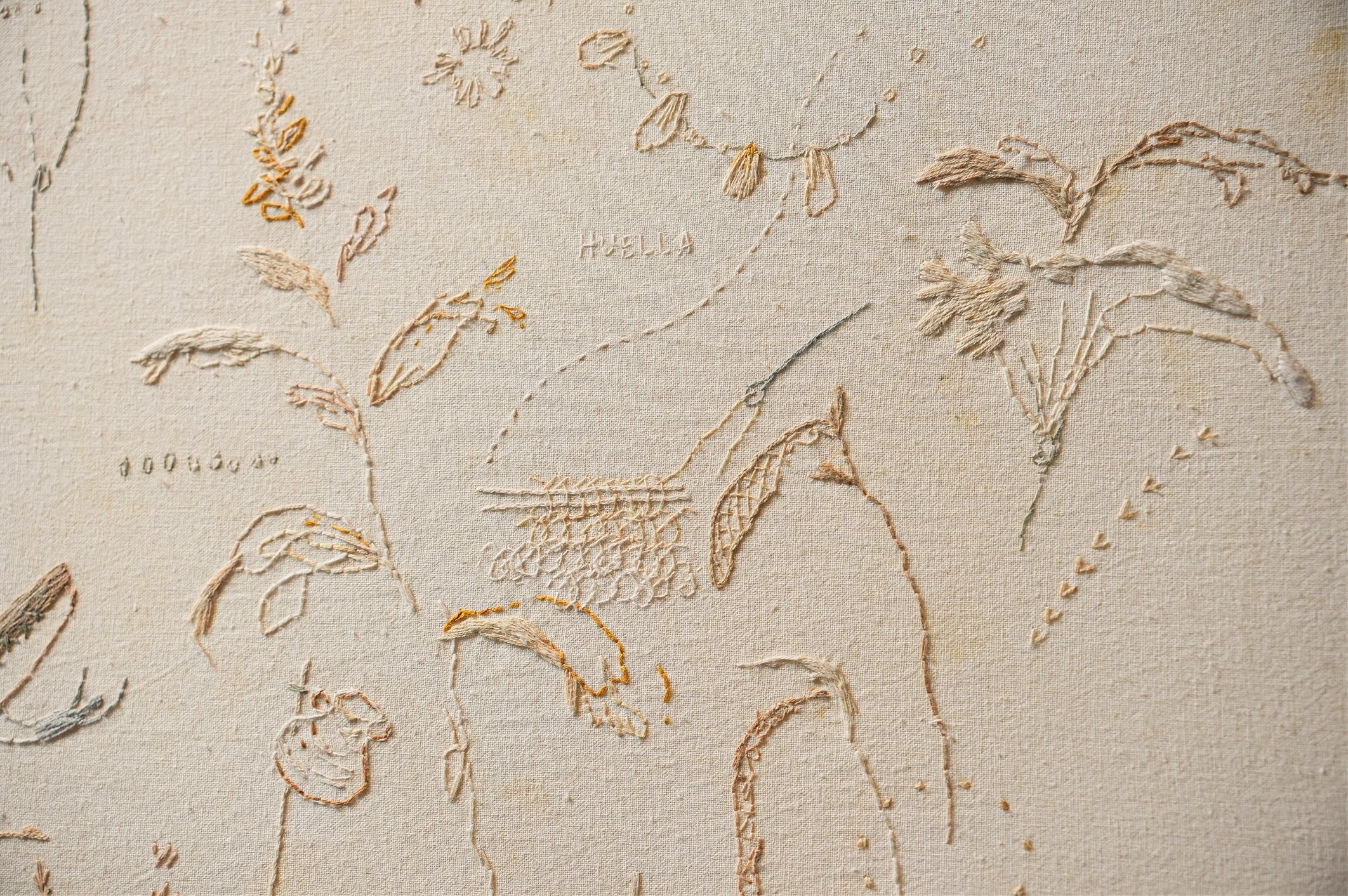

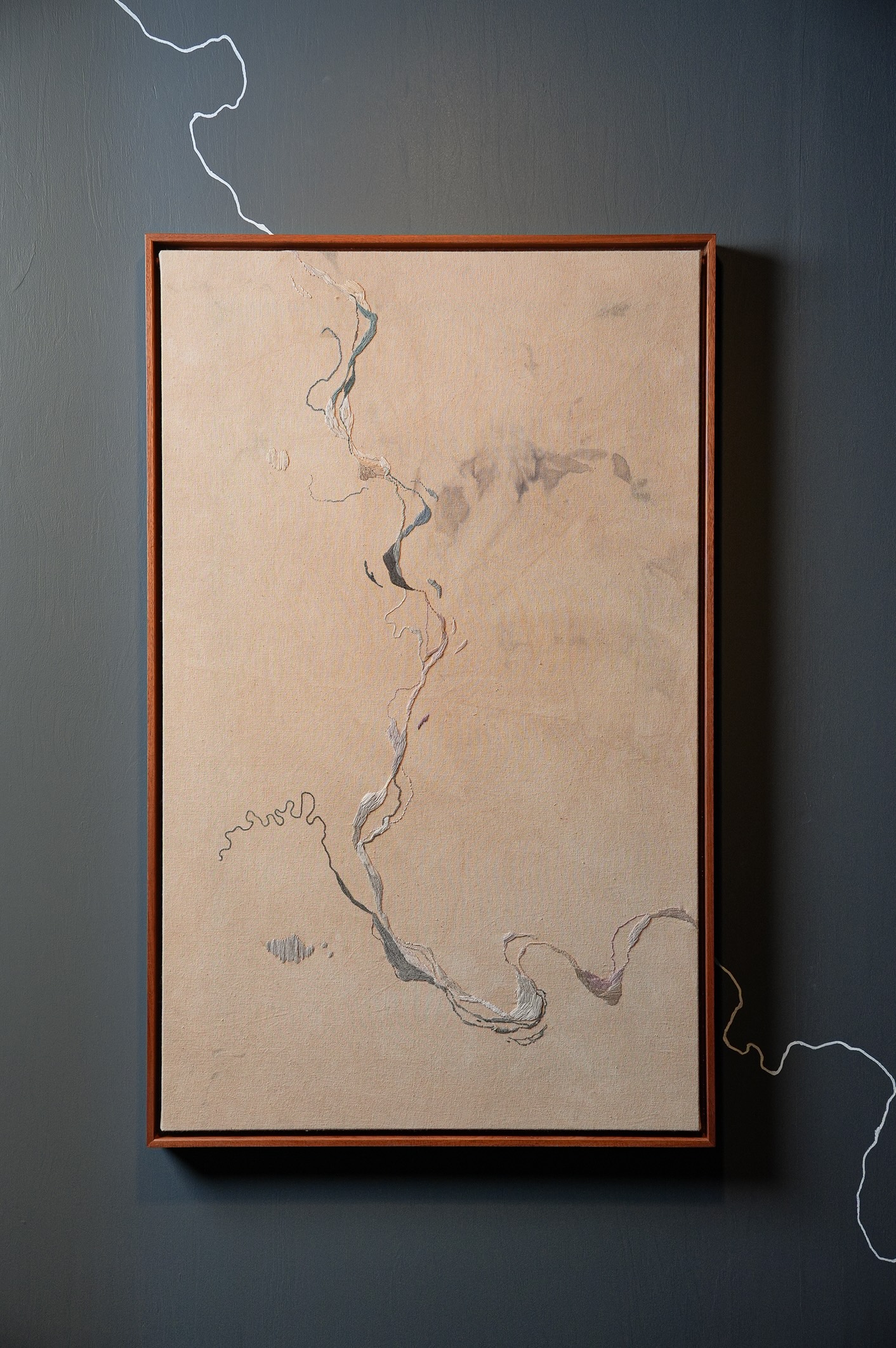

In a way, Había olvidado cómo se veía el horizonte perdiéndose en el cielo [I Had Forgotten How the Horizon Looked as it Faded into the Sky], her current exhibition at Servidor Local, offers a counterpoint to that earlier exercise: a series of embroideries of flowers and bodies of water, inspired by a trip to the Amazon—a territory shared by nine countries without physical borders. In the curatorial text, Mónica Nepote—a fortunate pairing—asks: “Do Antonia’s hands embroider, draw, or write?” Each piece, I would say, adds more verbs to the list.

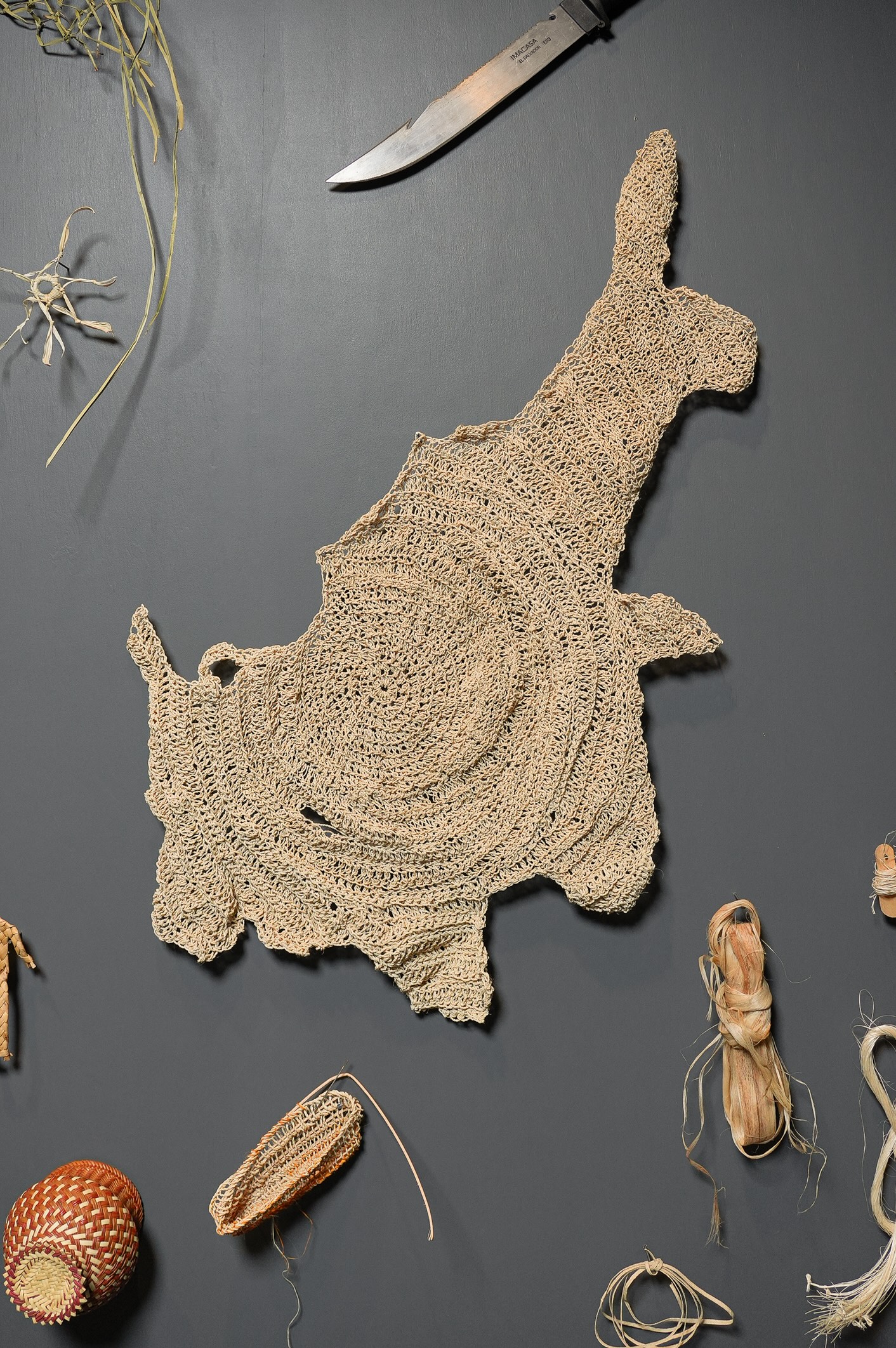

Antonia’s hands gather. One wall—the fibroteca (fiber library)—displays works and textiles she has either made or gathered during her travels through South America: native cottons, strands of her own hair, jute baskets, wooden carvings. Two textiles, whose shapes at first seemed abstract, revealed themselves as maps: Lake Texcoco (crocheted with chambira fiber, a palm native to the Colombian Amazon), Lake Chalco (made with horsetail plants gathered in Milpa Alta), and the San Gregorio Atlalpulco Lagoon (woven with wicker).

By using materials from one place to represent landscapes from another, Antonia underscores affinities that persist beyond geographic distance. She is interested in correspondences and in everything that slips past borders: tools that emerge across cultures, practices and meanings shared among species. There are countless examples of biomimicry (design inspired by nature)—the third new word I learned from her—such as anti-theft bags modeled on the woven nests of weaverbirds. In Plegaria de petición al agua (2024) [Prayer of Petition to Water], one of the exhibition’s most moving works, she presents the text of a request made “not to the nation, but first to the ejido (communal landholding system in Mexico)” to collect plants along the shores of the San Gregorio Atlapulco lagoon. “Why does water not have rights over its own body?” she asks. “Perhaps because water is a woman.”

Antonia’s hands make. More than a contemporary artist, she conceives of herself as a worker of materials; her practice, she says, is about creating the conditions for a plant to release its pigment. Another of her central concepts—she is a “highly conceptual” artist in the strictest sense—is material sovereignty: the ability to craft her own means and tools. The textiles of her embroideries, including the threads, were dyed by her using pigments derived from sawdust collected from carpentry shops, as well as flowers and leaves.

Finally, Antonia’s hands share. From August 9 to October 4, the ground floor of Servidor Local transforms into something resembling a school trip to a museum: curious objects displayed on dark gray walls, a small library, educational materials, a gift shop—with pieces by Carla Hernández, Alexandra Buitrón, and Nicolás Pradilla, collaborators in the exhibition—and even a take-home activity.

Translated to English by Luis Sokol

Published on Aug 29 2025