Review

Paola Dávila: in the Water-Sky there is not only blue

by Guillermo Boehler

At Patricia Conde Galería

Reading time

7 min

Tennyson’s plucking the flower and holding it in his hand, ‘root and all,’ and looking at it, perhaps intently. It is very likely he had a feeling somewhat akin to that of Basho who discovered a nazuna flower by the roadside hedge. But the difference between the two poets is: Basho does not pluck the flower. He just looks at it. He is absorbed in thought. He feels something in his mind, but he does not express it. He lets an exclamation mark say everything he wishes to say. For he has no words to utter; he’s feeling is too full, too deep, and he has no desire to conceptualize it.

— Fromm, E. y Suzuki¹

It is almost 200 years since the invention of cyanotype. The fact might seem useless to introduce the text, however, in 1843 Anne Atkins, British biologist, considered one of the first photographers and creator of the first book of photographs in history, the British Algae, used this blue technique to register the seaweed of the English coast. This is where the history of the technique ceases to be secondary to think about the exhibition Agua-Cielo by Paola Dávila² at Patricia Conde Gallery, inaugurated last April 20.

Dávila, together with exhibition curator Laura Gonzáles-Flores, insist on color as a discursive line: the link between color and marine and atmospheric tones, the loss of the limit between the sea and the sky on the horizon (Marea series, 2023); a path that begins with Homer recalling the lack of a word for what we call "blue" today. Works that experiment with exposure times and development, the chemistry of salts, the supports that receive the emulsion, the stain. Insistence on mixing expressiveness with the scientific discourse of the exhibition devices, glass slides for microscopes (Lámina I-VI, 2024) and watch glasses (large petri dishes, Alga XII-XVIII, 2023) as cultures of bacteria, of something that is alive, something that reacts, that metabolizes.

Atkins makes scientific plates with cyanotype; they are the opposite of Dávila's work. On emulsion-coated paper, the British scientist organizes the different species of algae and other plants for their description: whole on the support, she identifies their parts, leaves, bulbs, roots, no trace of the organic remains on the paper besides its shadow, nothing remains of the sea, everything is blue, everything is what it has to be, order of science, a very British and imperial order–more than Prussian, royal blue.

Let's not talk about blue.

Reds, oranges, earths, greens, whites appear–the material begins to breathe–the organic breaks the pure, the sea has not just one single color, temperature or light.

I want to lick the paper and taste the salt of the sea I long for.

Let's fight, let's insist on questioning the photo, the aseptic, the technicality, the purity of tones and the preciousness of representation. Its veracity, today, can no longer be sustained. The resolution and editing software of a cell phone camera are higher than those of a digital camera made specifically for this purpose. Pattern recognition systems and even artificial intelligence have proven to us that the sharpest, best rendered representation, the image with less noise, does not imply truth, does not imply proof, does not imply the trace of something, although it tries. It often misleads and confuses thousands of people in the process. Today's photographic devices evidence the partiality that has always existed in the photographic practice and in the gaze. The photograph was never "the truth," definitive proof, or proof of existence, but it has taken us two hundred years for the penny to drop... Now we can pay attention to what photographic processes give us.

The expressive nature of the photo, the use of emulsion, the alteration of light, time, speed and temperature, is no longer at the service of the precision or the look she tries to master. Paola Dávila experiments and pushes the boundaries of a technique that has been known for a long time, but that doesn't mean that she isn't precise—it is evident that she handled the material with great care and attention to achieve these colors and tones, forms, and presentations. Rather, as Gonzáles Flores indicates, the artist abandons representation, which gives space for an expressiveness that is not hers, that is to say, in these works the artist's expression is not important, she is the medium, she and the cyanotype. Her experimentation opens the field for the objects to express themselves, to breathe, to alter the chemical reaction, to alter the supports, to alter the forms and the stains.

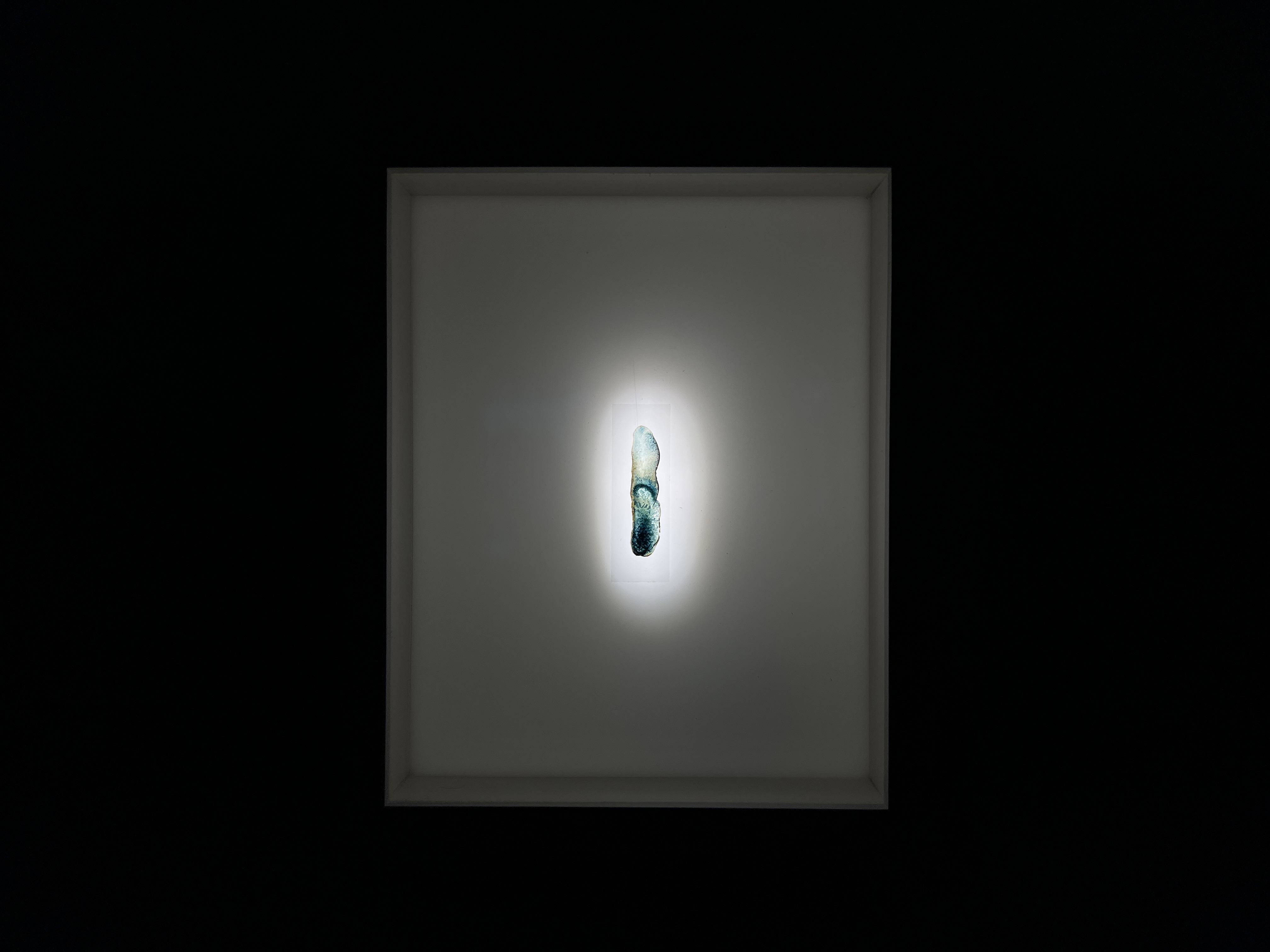

Get close and see how a grain of salt absorbs the water around it on a glass plate (Lámina, 2023) or on watercolor paper (31° 53' 48.552'' N, 116° 42' 38. 951'' W 10, from the series Marea, 2023); see the lumps of oxidation on textiles (as in Saloma XLIV, 2023), the orange and cream tones that emerge in them; the deep greens on silk, caused by the reaction between the salts of cyanotype and the proteins that make up the threads of the textile (Saloma XXIX, 2023); the transparencies and their shine (Lámina I-VI, 2024); the inevitable marks of the outline of the algae in direct and indirect contact with the supports, their inevitable dehydration, time as a stain (Laminariales XLI-XLIII, 2023). Despite the insistence on clinical aesthetics and the cleanliness of the samples on glass or watch glasses, which could refer to a scientistic eye or the flattening of the surface as in Atkins' plates, Dávila's pieces have depth and texture, which is noticeable in many of the works on paper and is enhanced in the installation that simulates swimming in a field of algae (Saloma XXXV-XLVIII, 2023). The risk of entanglement rejects the safety of the laboratory.

While we are accustomed to the flat use of cyanotype to produce photographic positives or to the white trace of objects on paper, here the artist takes advantage of the tones, the materialities and the three-dimensionality of the object. Whether it is the waves that break on the sand or the plants that, due to the change of temperature of the ocean, reach their limit, these generate marks that are located within their own possibility; they do not fit in an attempt of description and western and colonial precision of the scientific gaze, but in a position that makes the complexity of a non-human expression possible.

Despite the insistence, the sea is much more than blue, much more than water and sky, that is the discursive success of the exhibition text. The monochrome of the cyanotype and its characteristic tone opens a cipher of negativity: we no longer concentrate on the blue, we see all the other colors that were not named, all the other elements that make up the landscape, the wear and tear and the life they contain. The control that one can have over the support and the medium, when in direct contact with these elements, builds an unexpected trace, a trace that does not describe, but that shows the expressive power of these elements, something beyond them.

There are many more colors between the water and the sky, not only the royal blue, but all the life that does not care to name and name itself; the expression of an other that is not an artist, that is not human, of shades to be known.

The exhibition will be open until June 1, 2024.

Translated to English by Luis Sokol

1: Originally found in Spanish in Fromm, E. y Suzuki, D.T. 1964, Budismo Zen y Psicoanálisis, Fondo de Cultura Económica p.11. Thanks to Manuel Escudero for sharing this reference with me and discussing the expressiveness of the materials.

2: Thanks to the artist Paola Dávila for providing some information about the works, their processes and the assemblage for the writing of this text.

Published on May 12 2024