Interview

Paderón: Abraham González Pacheco about his exhibition at Campeche

by Eric Valencia García

Reading time

8 min

Eric Valencia García. How did this exhibition come about?

Abraham González Pacheco. The works originate from an entirely observation-based technique. They are filled with a lot of experiences and personal situations that I have been working with to generate a narrative. Recently, I have been visiting my town, San Simón el Alto, and I went back to see certain things that nurtured my work since I started, since before I entered school, such as the experiences with the ground and soil. I am the son of farmers, my dad has worked in the temporary worker program that goes to Canada. Since I was born, he has gone there to work. That program is a result of the North American Free Trade Agreement. I had to live through all these types of situations that are part of the idea of progress and that Salinas de Gortari tried to promote. Among them, the idea that concrete was progress. In my town there were dirt roads and, when these programs arrived, they replaced them with concrete roads. My father worked in construction at the golf club in Malinalco for a long time. When he wasn't working in Canada, he was working in construction. When I was a kid he would take me to the field or to work with him.

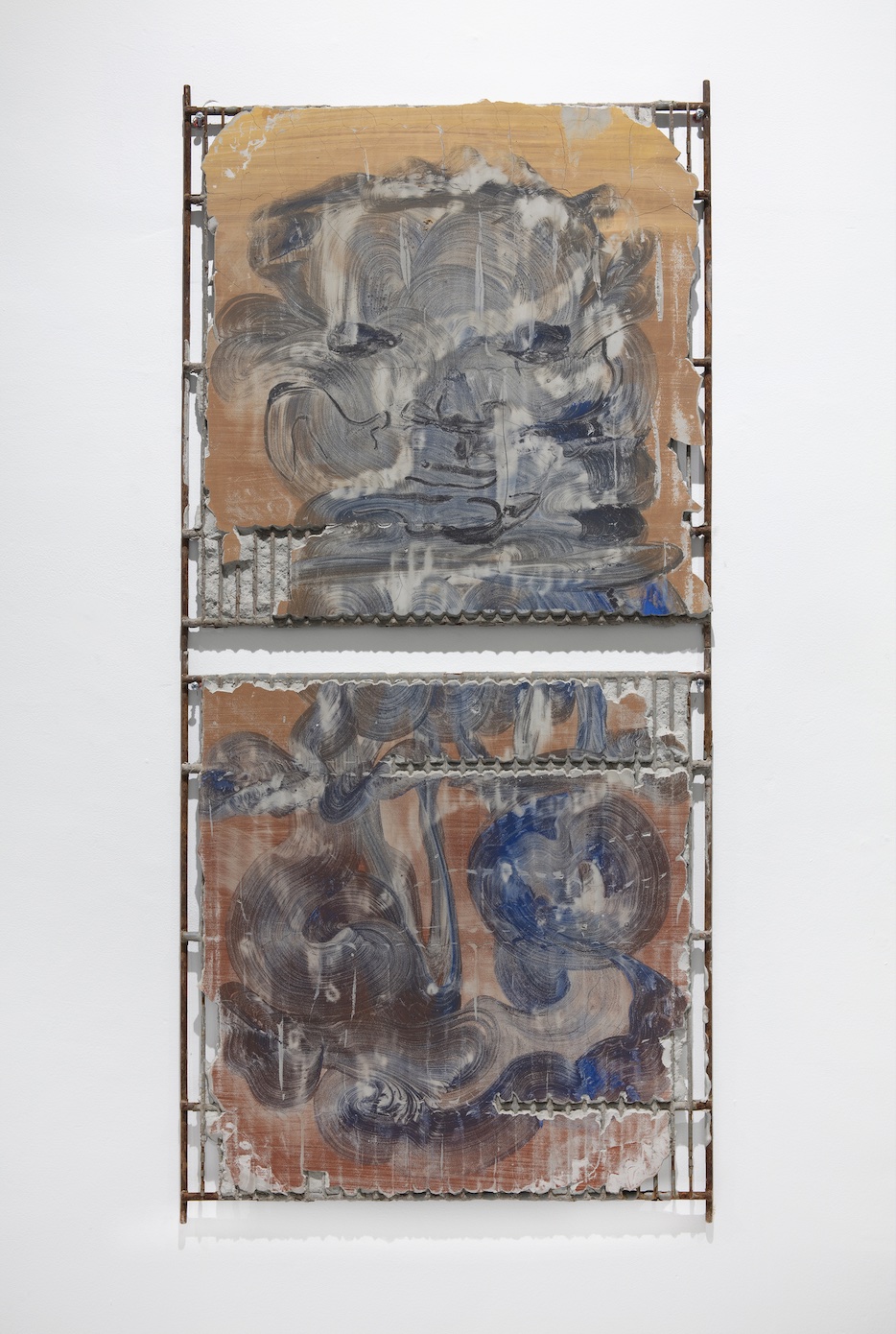

I was acutely aware of something I was seeing in the construction sites, and now after the experience I know that it is graphic or similar to a transfer. What caught my attention is that in the formwork, when the cement sets, it absorbs what the wood had: both the texture and the graphics are transferred to the concrete.

For a long time I was working on painting from a very personal aspect. Due to situations that I didn't like so much, I stopped painting during my studies and concentrated on graphics, drawing, installation and other things. I took up painting again about four years ago. Since then, I have been experimenting. I was invited to another exhibition and started painting some things. I had some pigments and different types of dirt, so I started to prepare some concoctions and I painted on some boards. Then I poured concrete on it and when I removed it I got a surprise: the paint was transferred to the concrete, although in some unconscious way I was expecting it.

I realized that this technique is a monotype. It looks like fresco, but it is not. As I kept working on these pieces, I noticed that there were situations that slowed me down and that I could not control. Situations that have to do with the weather, the setting, the time it takes for it to dry; they prevent the image from transferring as I drew it. At first I saw it as a conflict with the piece, but then I began to see it as a quality. That's where the work begins to overflow into another discourse about the process of things, of the randomness of things and how they work.

I have been told that my work looks like an archeology of the future. That they are murals that come from a time loop. You know that in my work, most of the time, I've been talking about this because my town doesn't have a history. It is one of those little towns that came out of nowhere and there is no record of it; all its history has been nurtured by anecdotes that have been copied from generation to generation and have been extracted from different places. And though my town is very close to Malinalco, there is no pyramid there. Although there has always been a myth that there is one somewhere. The project I did at Biquini Wax was about that, about the artist's potential to create a story or a lie out of nothing. Like Román Piña Chan and Carlos Hank Gonzalez when they made the archaeological zone of Tenango del Valle.

EVG: Can you tell us about the title of the exhibition?

AGP. The exhibition is called Paderón because my grandfather always said we should go to the "Paderón" to work, which was a place where peas were planted, near where the pyramid is said to be. It’s a place with smooth crags, it is said that they are walls, it was called "Paderón." The word does exist and it is a type of wall that divides the land in the fields, it is made of stone or adobe, looks similar to a ruin of some sort. I used to tell my grandfather: "That's not how you say it, grandfather, it's called a wall [pared]." But how can you make people change? So, rather, I embraced this word to use it as the title of the exhibition, to have a direct reference to that place, to that specific moment.

EVG. For this exhibition, the metal structure of the works is much more evident than in your previous works. Why is that?

AGP. Although the pieces are heavy, they can be moved, they are portable. You can't move a mural. They are like the murals I do that can be erased, but these can be taken from one place to another. As for the structures, it's because I didn't have the money to send them to a blacksmith because they are very specific. What I did was to look for the material near my house, in Tepoztlán. I started to find these that are made of industrial waste and have a stronger and more resistant structure.

EVG: Do you think we could think of these works as murals? Perhaps taking more into account their material qualities than their extension. And in this sense, as paintings that deal with architectural issues?

AGP. Of course, we could also see them as a structure, as a sculpture. That's why I consider this to be painting. It has other qualities, like glazes, layers, and curtains of color. I could say that the metallic structure itself is a layer, that the concrete is a layer of paint. What we see on the surface is also, obviously, paint, another layer. That's why we wanted to paint the walls of the gallery as well, because the wall that holds the painting and the wall behind it are also layers. In addition, there is an issue that has to do with the palimpsest: to be able to see the landscape through these layers. The palimpsest as a horizon, as a way of understanding painting through these structures.

EVG. The most traditional theory considers that painting is dedicated to generate an illusory space in a plane...

AGP. Exactly, in the illusion. And this is completely more concrete, so much so that it hurts my back (laughs).

EVG. And the fact is that matter also gets damaged. In the case of concrete, it breaks…

AGP. There are things that look like a technical error (he points out a detail of a piece where the concrete looks like it has "peeled away" from the metal structure), but it is a quality because it is a layer, then the metal layer comes and then the concrete layer. I keep notes on how it works because I want to understand the process, but sometimes I'm not going to understand it. It's impossible to finish a piece and say, "I wanted it to be like this."

EVG. We could also think that progress is a myth that is partly based on the idea of mastery over the material. Or to put it another way, of mastery over nature, through technical processes, to make the material behave exactly the way you want it to. But there are other thinkers who propose the idea that the material also expresses itself. In these terms we do not see technical "errors", but different types of relationships between the agents involved in the formulation of the "material."

AGP. That's what really amazed me. It's not exactly that the material has a specific life, but rather that it responds to situations beyond my control. And I think that as human beings we should understand that the universe is wider than what we can control. Those "mistakes" are tangible proof that we cannot control the universe.

EVG. It's the delusion of control that has led us to....

AGP: To this chaos! And you see, it even gives me goosebumps, because not being able to control is a fundamental part of this exhibition.

Paderón, by Abraham González Pacheco, can be until March 21st at Campeche, Campeche 130, Roma Sur, in Mexico City.

Translated to English by Luis Sokol

Published on February 10 2024