Interview

Onda MX + Trámite Buró de Coleccionistas Diffusion Prize: Prisciliano

by Sandra Sánchez & Josephine Dorr

Reading time

7 min

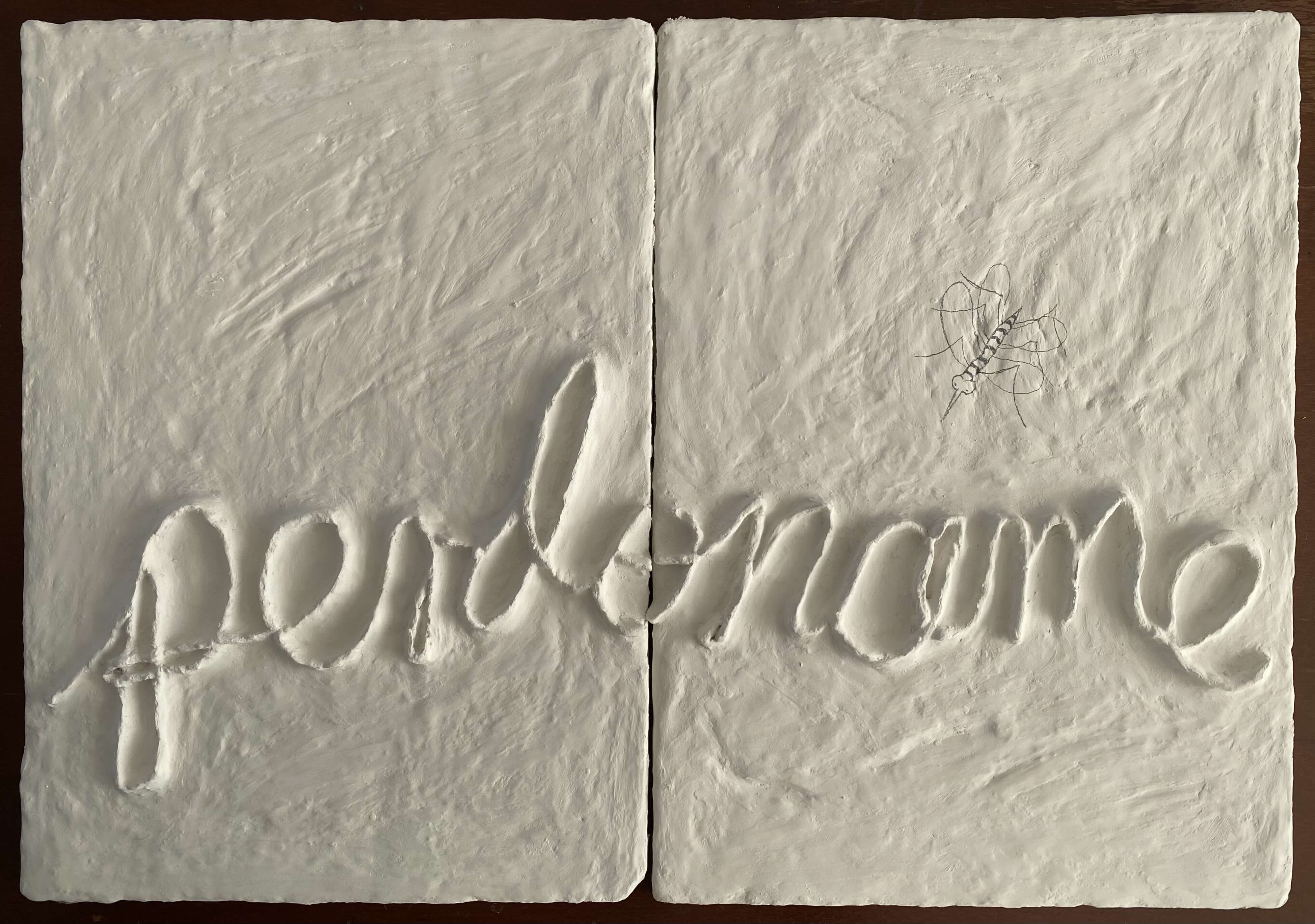

From October 10 to 20, 2024, the 008 edition of Trámite Buró de Coleccionistas took place in Querétaro, focusing on the theme Desire. Affective Movements. Onda MX partnered with the platform to select an artist and promote their work through an interview. Josephine Dorr (founder and director) and Sandra Sánchez (editor of the magazine) chose the work of Prisciliano, who presented LA SUERTE ESTÁ ECHADA, a cement and graphite surface featuring the drawing of a mosquito and the phrase “perdóname” [forgive me]. Both agreed that the work holds an enigma—highlighted by the presence of the mosquito—within a straightforward phrase that resonates differently with each viewer. This dual relationship, between literalness and indeterminacy, made Prisciliano the winner of the diffusion prize.

Prisciliano Valencia was born in 2000 in Jacona, Michoacán. He completed his degree in Fine Arts at UMSNH. He is the co-founder of the artistic project Sangre Caliente, where he has organized and curated various exhibitions in Michoacán. His artistic work focuses on affective recovery, playful violence, and identity. He received the acquisition award at the Salón Estatal de Acuarela. He participated in Mark Bradford’s solo show at the Zapopan Art Museum and with Patricia Belli at the FEMSA Biennial in Michoacán. Recently, he exhibited at the XIII Alfredo Zalce Biennial (0100), and in Tomo 006, 007, and 008 of Trámite Buró de Coleccionistas, as well as at Espacio Cabeza, Studio Croma, and Tlaxcala 3.

What role does the archive play in your creative process, and how do you use your personal archive to reinterpret the history of your community?

The archive is crucial for me. I always try to keep it close, whether physical—composed of materials and objects I’ve collected like stones, feathers, animals, soil, drawings—or digital, with the thousands of images I’ve stored. I constantly rely on it in my creative process. I use elements I’ve preserved to create pieces that help me construct a dialogue with my identity and the context in which I live. Earlier this year, I used petroglyphs found on the Curutarán Hill, right across from my house in Jacona, to create some pieces. One consisted of cement supports in the shape of animals with low-relief drawings, and the other featured chalk drawings of anthropomorphic figures directly on the exhibition space walls. Currently, it’s not possible to access Curutarán to see the rock art due to issues with drug trafficking, so I thought of bringing these scenes into view again until the conflicts subside.

In your work, you mention the use of materials like photographic archives but also cement, sand, and concrete... Could you elaborate on how these materials, as well as excavation and sediments, reflect your personal experiences and the relationship between construction and memory in your pieces?

I treat these elements as a living archive. I recover objects that reflect a closeness to my environment, using materials I find around me or even in my home. Sometimes, they are very specific materials. For example, in my recent solo show Transuente at Tlaxcala 3, I presented an installation titled Lugar seguro II, consisting of seven arrows cut from the railing in my parents' house and two swallow nests we had in the garage. I found it fascinating to have these resources interact, thinking about how the house’s protection became a weapon to add another form to the home.

Language runs through your body of work. What do you see as its role or performative aspect in your pieces?

I often use language as wordplay in the titles of some pieces, which helps complete a reading of the work. Other times, it becomes asemic writing, appearing as scratches, marks, and strokes on the surfaces I’m working on, like cement, wood, or fabric.

How is your relationship with Jacona, the place where you live? Could you explain the impact that daily violence in Michoacán has on your practice and how you address it in your pieces and projects? In Jacona, I’ve already had exhibitions and processes to channel my creative frustrations, and now I like to think of it as a kind of fictional territory I can turn to safely to safeguard my thoughts. It’s a place to excavate and recover feelings, but also to deposit others that may or may not be expressed. Keeping them in Jacona gives me the ability to observe my processes from a distance and reflect on my concerns before beginning to work on them. Jacona is the starting point for building my material production.

As for the violence, no one in Michoacán or other states is unaffected by the daily violence that permeates our daily paths. Given how close it is to everyday life, it’s impossible for it not to be implicitly present in the processes of creating a piece. I never treat violence as the final outcome but as a deeply rooted memory that helps me understand myself and allows me to stay in the present in order to create. For example, in 2022, I painted a sort of postcard on a white background with two red drops. The piece is called Ramona, after the first LGBT+ person I knew in Jacona, who was killed that same year. The postcard was the landscape where I could find her.

What do you understand by “playful violence” and how does it influence initiatives like the self-managed space Sangre Caliente that you co-created in 2022 with Osvaldo Maldonado, and the Armarse exhibition you organized at Espacio Sin Nombre in Guanajuato? What does it mean for you to collaborate with other artists in self-managed projects that explore this relationship between violence and affection?

In the early stages of Sangre Caliente, we sought to bring together the interests of our generation and discuss them. Initially, we weren’t sure what concept we wanted to work with, but when talking to friends in the scene, violence always came up as a recurring theme—not as something meant to be aggressive, but as a daily concern we played with. What interests me most in these collaborations is the ability to share the ways in which our common experiences converge, finding ourselves together and thinking about protection, intimacy, play, and memory. I see them as allies in resisting rather than committing violence. From these motions, we produce pieces as vestiges of the playful impulses that drive us to remain in a cycle of seeking to assimilate the experiences we share. Between the collective and the private, we find the connections that allow us to express the construction of our identity.

In your piece Lugar seguro presented at the FEMSA Biennial in 2022, we see scorpions, and in your recent work at Trámite this past October, there’s a mosquito. Can you tell us more about the meanings these creatures hold for you?

For as long as I can remember, I’ve always been a bit obsessed with small creatures. My first real interaction was when I was stung by a scorpion as a child. It was hiding in the couch, waiting to scare my mom, and I just felt the sting and we ran to the hospital. Since then, I’ve turned to them in drawings, toys, and everything—I no longer wanted to see them with fear but as something familiar. In trying to adapt this ritual to my work, I’ve brought them back and used them as protectors of my language. They guard the piece, accompany it, and protect it.

Tell us about your current projects.

I’m currently working on the continuation of some projects I started this year. For example, the latest installment of Tres pases terrenales, ephemeral exhibitions I’m doing with my friends Thomas [Bourgat] and John Mark in our home territories. I’m also continuing to delve into the affective recovery in Transuente, an archival fiction project I created with Alí Cotero. At the same time, I’m pursuing management efforts for Sangre Caliente in collaboration with independent projects in Michoacán and other states.

Translated to English by Luis Sokol

Published on November 24 2024