Essay

On 'Para Morelio'

by Rocío Cárdenas Pacheco

Collective exhibition at PEANA

Reading time

7 min

PEANA Gallery in Monterrey, Nuevo León, is presenting from September 2021 to January 2022 the exhibition Para Morelio, dedicated to the doll with white ivory-like complexion belonging to that beloved child of Múzquiz, Coahuila—Julio Galán.

The central axis of the exhibition offers a rereading of Galán’s work, while ambitiously aiming to revise the history of neo-Mexicanist painting. The curating was led by Deslave (Mauricio Muñoz and Andrew Roberts) and Ana Pérez Escoto. The most interesting contribution is the show’s queer perspective, especially since it falls short at the historiographic level. Para Morelio even chafes against that reductionism from which this artist has been read for more than three decades. In the local area of Monterrey, explorations of conservativism and the representation of the body in Julio Galán’s work have been analyzed as though he had been the only artist interested in these themes. First, this has to do with him being a dandy belonging to the San Pedro elite; second, it is because even within his own context he was never fully accepted—as evidenced by his success outside of Monterrey.

This double tension has left many other creators out of the historiographic narratives—those who, like Galán, created works throughout the eighties and nineties examining the dynamics of sexuality and difference, such as Rosa Ana Garza, Juan Caballero, Juan Alberto Pérez Ponce, and Juan José González (to name just a few).

A factor counting against this show is the null presence of young local artists—which, though obvious, highlights its lack of interest in the local scene, where there exist gaps in the aesthetic discourse related to sexual identity and non-binary gender models.

This point seems crucial to me, so as not to continue making circles on the floor about Julio Galán’s omnipresence as the only artist in the history of art in Monterrey. Furthermore, he was privileged in terms of class, education, and social presence in that territorial space where all is exonerated: the municipality of San Pedro Garza García.

I propose that we travel back in time. Let’s go back to the beginning of the nineties. Imagine for a moment Julio entering the glamorous Kokoloko*1, accompanied by Mara Sepúlveda or Zulema Olivares, decked out as vampires or with chains around their necks, opening the runway or dropping the needle on George Michael records like Faith or Listen Without Prejudice. On returning home he liked to run at full speed on Avenida Constitución, and in the early hours of the morning he would stop at the Mode supermarket so that his driver could buy him some Frosted Flakes and milk. He loved being received with a set table in order to have breakfast with Morelio seated at the head. He closed the night by watching the first rays of the sun from his apartment on Chipinque. The figure of Julio Galán from the point of view of the local context, both fictional and real, allows us to read his work while deviating from the “as it should be” of neo-Mexicanism: something this exhibition carries out with success.

Nevertheless, Para Morelio not only falls short in historiographic terms, but also—unfortunately, in what is most dire for me—in the poor quality of the works’ facture. On the other hand, this exhibition offers an accompaniment to Galán’s works, but it is ambiguous: the artists have missed the opportunity to coexist in a much more interesting and critical way with these pieces, in terms that could generate broader dialogues with the local artistic community.

I felt sad about this; the show gave me the feeling of the end of a party, but without much to remember. In particular, this is because none of the young artists are from around here—all have come from outside. In the words of researcher Iván Acebo Choy: “the term ‘queer’ from the point of view of theory is a discussion that in the contemporary sphere calls for inclusion. From its historical context, at the beginning of the eighties, it had a very fragmented origin: among lesbian women, and following that its preponderance among gay men, and from there it was decanted in various discussions as intersectionality became popular. But today, sometimes ‘queer’ is used as an umbrella term that theorizes a diversity of identities or anti-heteronormative subjectivities. And moreover, it is one more letter on the LGBTQ+ spectrum.”*2

Queer viewpoints appeal to open discussions with segmented chasms that seek many things and, in many cases—such as in this show—that do not configure critical questions about the visitors’ queer context, their local references, or their problems when accessing productions marked by privilege, like that enjoyed by Julio Galán throughout his artistic life.

I’m sorry to be repetitive, but this is a serious problem in local historiography that extends to a fundamental moment of inflection in establishing a point outside the privilege of being called Galán. If this exhibition was not organized by one of his past validators (Guillermo Sepúlveda, for example), then why fall so short? Why not operate in a more radical way? Why waste the party and show things from comfortable discourses, from safe, common places?

Galán was self-demanding, in extraordinary terms. The presentation of a clay sculpture by Ana Segovia, You are gonna end up with me (2021), of a mariachi with a painting stuck in his ass, might have provoked a laugh in him, especially as a critique of the mariachi’s role as icon in the movement known as neo-Mexicanism.

The artists Rafa Esparza, Romeo Gómez López, Barbara Sánchez-Kane, Ana Segovia, and Frieda Toranzo Jaeger dialogue across three rubrics analyzing Galán’s work: gender as artifice, clothing as based in indeterminacy and performativity, and, lastly, pictorial strategies, among which stand out the toys, objects, and collage used with the aim of unpacking traditional notions of sexual identity.

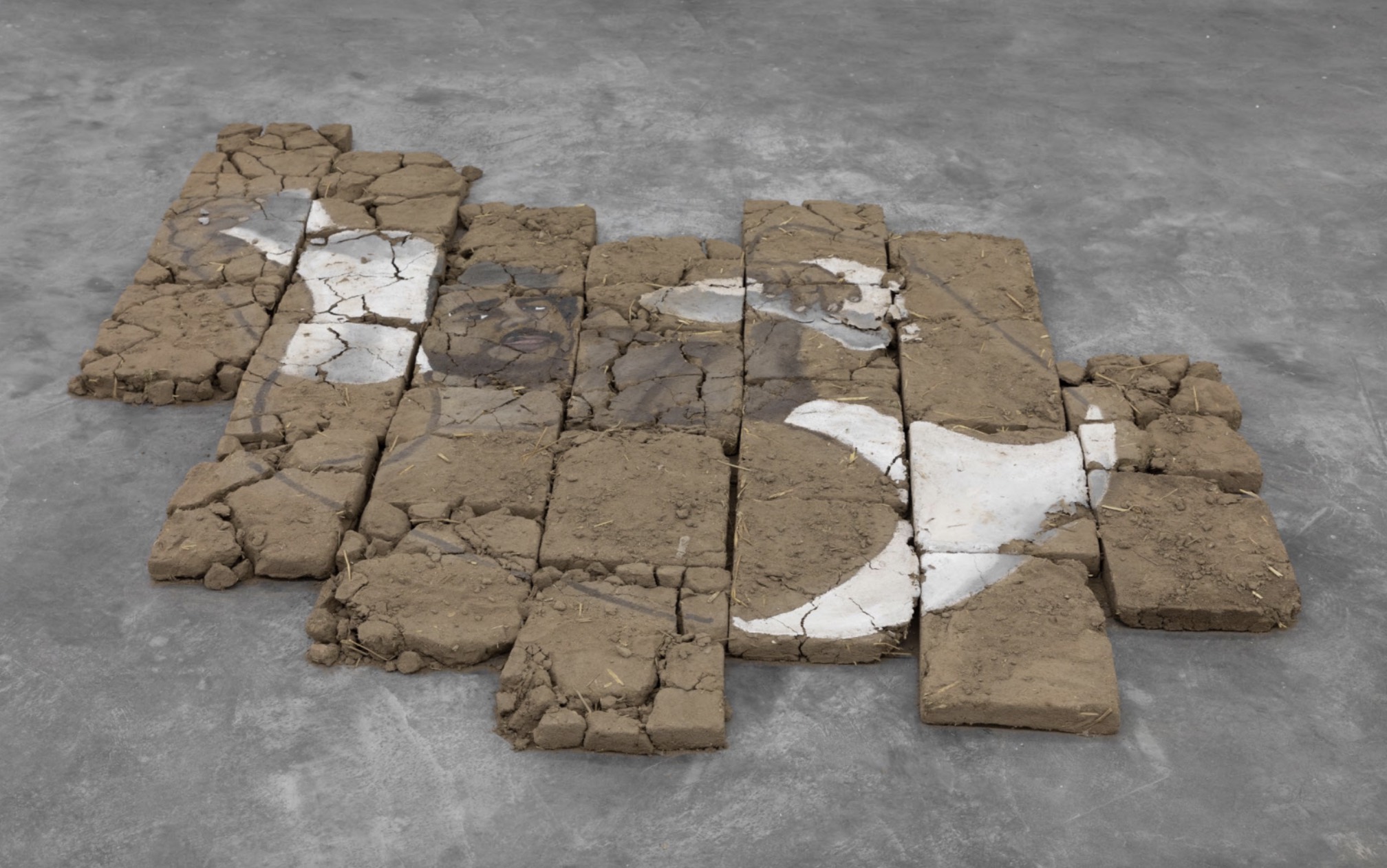

Rafa Esparza uses adobe on the floor to make portraits of queer people whose ancestry is mestizo, which suggests a reading based in an action of empowerment by showing us their garments, highlighting that the color of adobe blends with the color of the skin of the protagonists.

Bárbara Sánchez-Kane presents a painting and a sculpture made with rawhide, evoking garments. Romeo Gómez López’s sculptures, mainly carried out in transparent blue acrylic, seemed to me the most successful of the show in dramatic and spatial terms, since they include a musical installation that calls the viewer to meet these objects-sculptures-toys.

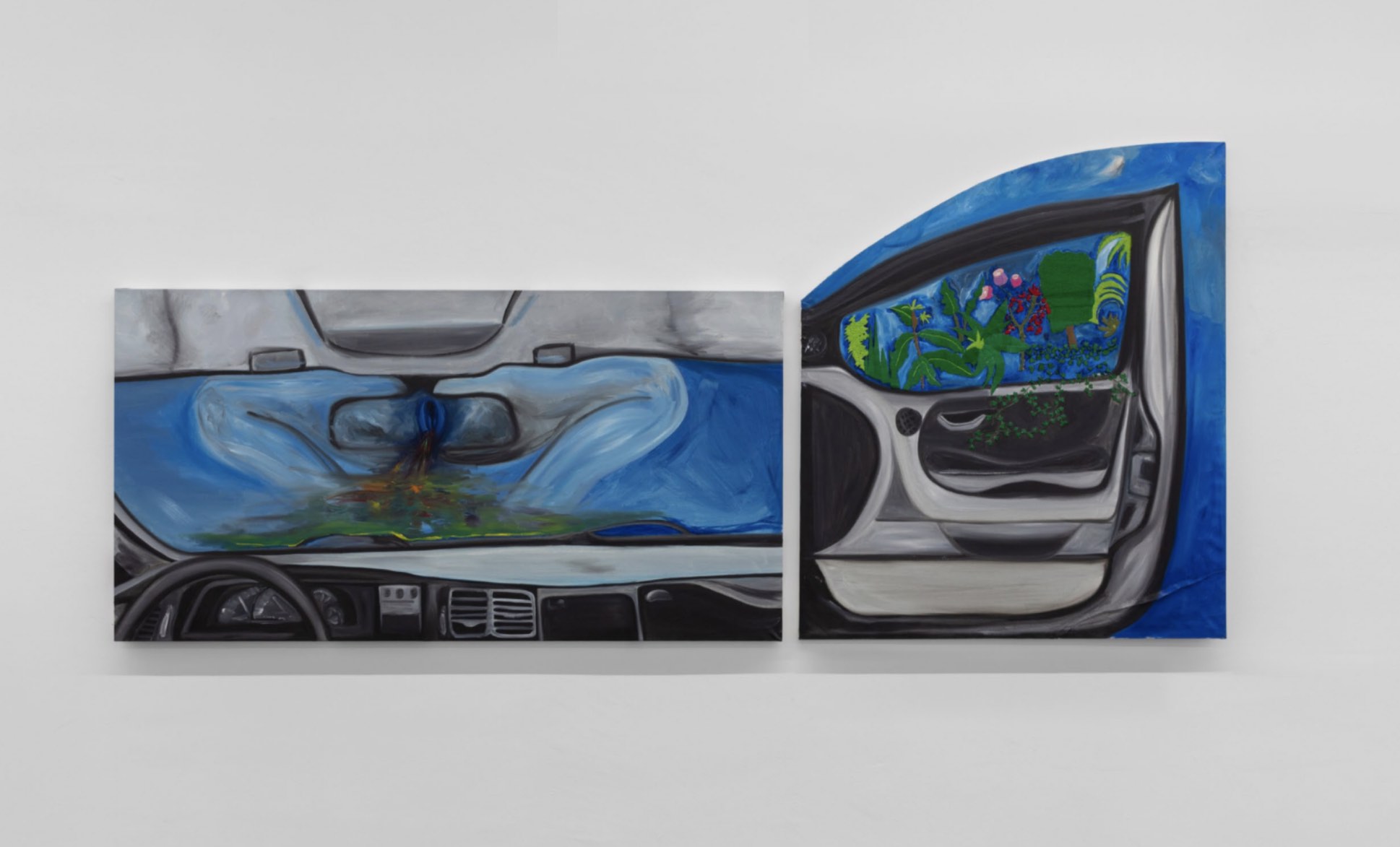

Frieda Toranzo Jaeger is a painter who shows cars, landscapes, and embroidery in unconventional settings with the aim of turning them into seductive vaginas in the middle of windshields. She also depicts fluids with colored threads roughly stitched into the canvases.

With Para Morelio I was left wanting in terms of facture and discursive proposal. It was a good effort, but in order to break into the queer art scene without hierarchies, irreverence needs to be accompanied by obsession, commitment, ambition, and the urge to end the party with a memorable sensation—all while seeing others from a critical situation that is ready to overcome the joke, the jotilencia, and the commonplace.

— Rocío Cárdenas Pacheco

Translated to English by Byron Davies

*1: Monterrey nightclub on Padre Mier between Pino Suárez and Cuauhtémoc. It had three floors: the first played pop, the second electronic music, and the third rock.

*2: The most recent research project of Dr. Iván Acebo Choy (Doctor of Science in the Arts at the University of Havana) seeks to analyze the new visual dynamics that contemporary queer artists use for the construction of sexual otherness, as a way of approaching Latin American and Caribbean queer historiography. He is also an independent curator. Translation of comments taken from an interview on December 12, 2021 in connection with the book Los Juanes antagonistas del cuerpo en diferencia.

Published on January 6 2022