Review

On 'Painting and Pharma' by Enrique López Llamas

by Isabel Sonderéguer

At LLANO

Reading time

8 min

A few months ago, when the exhibition [Transición fundido a blanco] ([Transition Fade to White]) still occupied its space at the Museo Carrillo Gil, Enrique López Llamas uploaded some stories suggesting a relation between the abstract art of the 1950s in the U.S. and the designs of psychopharmacological pill boxes. Ever since that day—the 2nd of March, 2022, to be exact—the intrigue has hardly disappeared from my mind. I share with the artist the desire to understand more deeply the link, one that is so direct in visual terms, between these two phenomena.

Perhaps the interest stems from having grown up in a generation replete with mental health drugs. More than once we chatted about this in the museum and recognized that we all knew someone who takes pills, not to mention those of us who take them ourselves. There was even one instance when my sister went to see [Transición fundido a blanco] and she started crying; in fact I looked at her in surprise, since the medication covering the room is the very same as one that I take.

Like with Enrique, this curiosity arises from a personal and affective situation, but it expands to reach larger-scale problems within the history of art: if both phenomena occurred at the same time, it does not seem completely irrational to think there might be a relation between the two. Perhaps pharmaceutical companies used works by famous artists of their day in order to legitimize their psychiatric drugs?

The project being exhibited at LLANO is called Painting and Pharma. It is one more step in the exploratory process that López Llamas has been traversing for the last couple years, in which he has employed different approaches to the pictorial field, all based on a medical pretext. The search began when he found a medication box in his father’s room and could not help but notice its similarity to works produced by Ellsworth Kelly. From that moment, he began a collection of packagings, convinced that if he eliminated the textual information they normally bear, they could then resemble abstract paintings from the last century.

For this exhibition, he took a couple steps back, not because the already-familiar story had been exhausted, but rather because he was interested in exploring the relation between pharmaceutical companies’ graphic design and pictorial production in the U.S. in the 1950s, bearing in mind such figures as Frank Stella, Sol Lewitt, and Mark Rothko.

Researching the history of the pharmaceutical industry, he realized that the dates on which psychiatric medications were launched on the market corresponded to the high moment of exposure for abstract artists in the U.S. López Llamas makes clear that he has not been able to find any documentation or hard data that would confirm a direct relation; nevertheless, this would seem to be secondary, since what is of interest is the speculative exercise he carries out.

With a basis in these intersections, the artist creates micro-stories around the similarities between the graphic design of packaging and the art scene of the time. At the gallery, Enrique and I started to play: “Perhaps one of the directors of the pharmaceutical companies was an art dealer.” “Or he just went to MoMA and saw the Frank Stella exhibition and asked his designer to build on that.” Through this exercise, López Llamas finds a new path, which is, at the same time, a return to the way in which his plastic creation has always operated: a space allowing for the free play of the imagination around those myths that course through our cultural system.

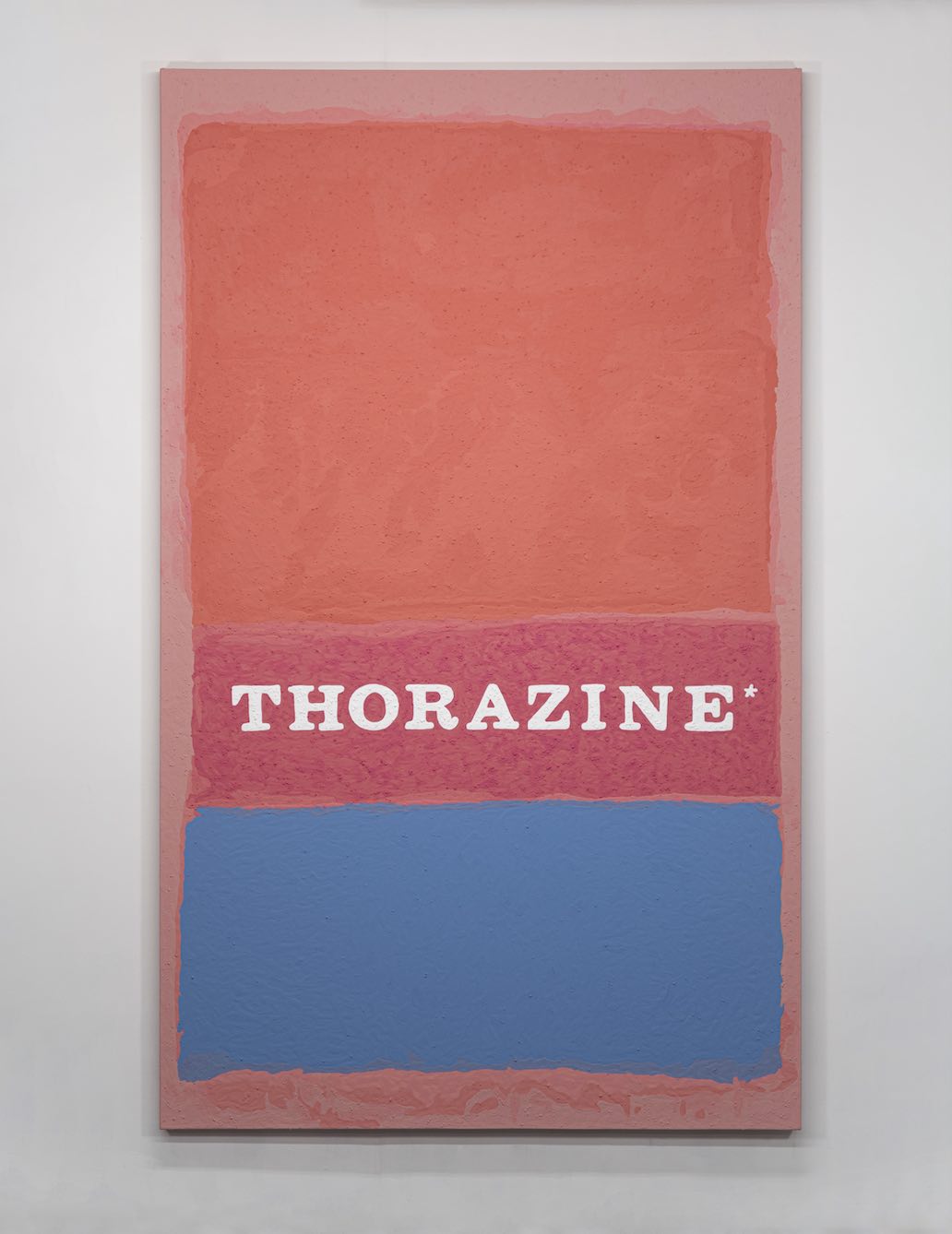

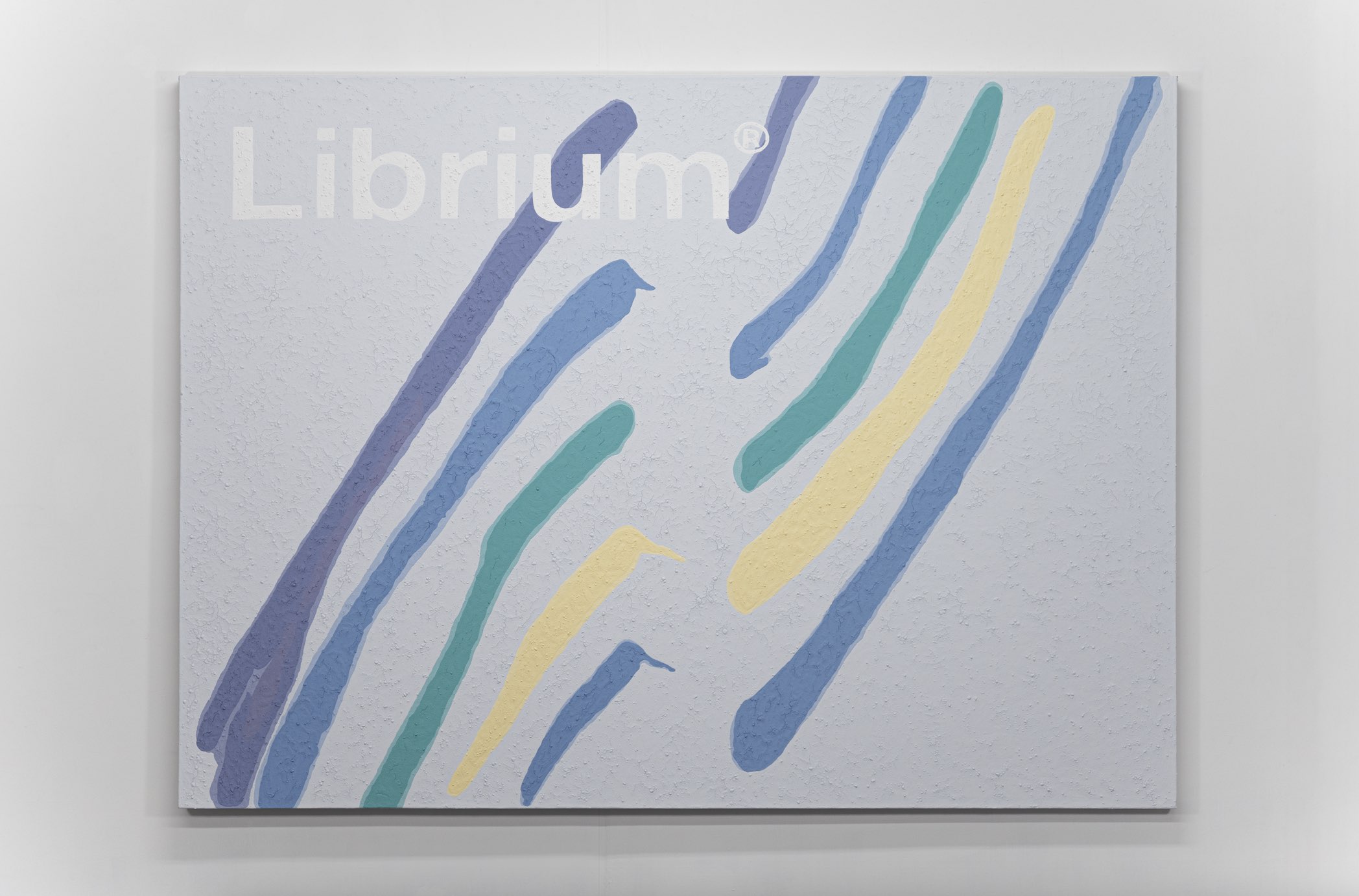

In the exhibition’s pieces, he uses the greatest exponents of color field painting, a pictorial movement that has marked his artistic education ever since he was a student. Some of the reproduced pieces are ones that he has seen in person. The creation mechanism is relatively simple: he reproduces a work made the same year as the release of the drug whose name appears in painting.

In chronological order, the first psychiatric drug launched on the market was Thorazine, an antipsychotic, in 1954, the same year as the Rothko piece accompanying its name. The piece called Marsilid replicates an Ellsworth Kelly and takes up the name of the first antidepressant. It was originally used to treat tuberculosis, until it was discovered that it also worked for depression. López Llamas says that there is even a photo showing tuberculosis patients dancing, meant to demonstrate the drug’s effectiveness.

Normally, he grinds the medication named in the work in order to combine it with the pigment, using this mixture for painting. In the cases of Thorazine and Marsilid he could not do this, as they were both taken off the market. At that time there was not very strict regulation, and it was later realized that they caused permanent damage to the kidneys, thus leading to patients’ deaths.

The painting Librium, an anxiolytic, reproduces the work of Morris Louis, who carried out watercolor drippings in which the color gradually faded: an exercise that López Llamas aims to replicate in his painting. At this point, the investigation seems to take on a life of its own and to postulate new connections between art and pharmaceuticals. The artist discovered, as soon as the work was created, that one of the side effects of this medication is to blur the patient’s vision, a bit like the blurring effect of a painting. The fictions take their own course and create new intersections via coincidences and accidents.

In the exhibition one can also see works by Joseph Albers, Agnes Martin, Jules Olitski, Kenneth Noland, and Sol Lewitt, each related to a different medication. The show seems to suggest that it deals with real packaging—and if we did not know the contrary, we might well believe this upon entering the gallery—but López Llamas in fact seeks to display the formal possibilities of graphic design, playing with color fields, lines, and geometric figures that build up volume. Although upon entering LLANO what we see is a showcase of forms, there also exists a play with fiction and its own possibilities of world-creation.

The works do not have a defined scale; the artist wanted the reproductions not to share the size of the original paintings, but rather to be smaller. These works by López Llamas are compressed, allowing him to establish a dialogue with the idea of compression, just like the pills.

The installation was carried out with a nod to the way that the original paintings were exhibited. The color of the walls, the works at eye level, and the sitting benches all replicate the model of the white cube established at MoMA in that same period. A tension is created between art’s visibility in the great international museums and the secrecy of psychiatric drugs. Inserted into this display format, the medication is sacralized and led to confront the viewer with the social abandonment of the mentally ill. One can also think of the mythologization of madness in the history of art: that is, the figure of the artistic genius who would typically be someone suffering from some affliction of the soul.

What is the power of art when faced with a pharmacodependent society? What about those abandoned patients, with hidden mental health problems? The play of textures within the paintings functions as an allegory of medical treatment and of the way in which our society deals with these problems. When there is less medication mixed with the pigment, the paint then breaks down—just like a patient who doesn’t take their pills. Nevertheless, it is necessary to get closer in order to see the fractures, hidden from those who refuse to go deeper.

López Llamas’s speculative and imaginative exercise functions as a game of shapes, colors, allegories, and myths. At just that moment when these artists exhibited in the great museums, huge fictions were created around their personas. Finally, Enrique tells me that, once the exhibition opened, a visitor said to him that it seemed as though a teacher at the Bauhaus had gone to work at some pharmaceutical companies. The theory—almost a conspiracy theory—that he has been developing in recent years, in the style of a detective, could very well be true.

— Isabel Sonderéguer

Translated to English by Byron Davies

Published on June 3 2022