Review

On "Simbiontes" by Fernando Zarur

by Julián Madero

At Proyectos Monclova

Reading time

4 min

You might sometimes think, in the middle of this edgeless road, that there would be nothing after it; that you would find nothing on the other side, at the end of this plain split with cracks and dried arroyos. But yes, there’s something. There’s a village.

“They Have Given Us Land,” Juan Rulfo*1

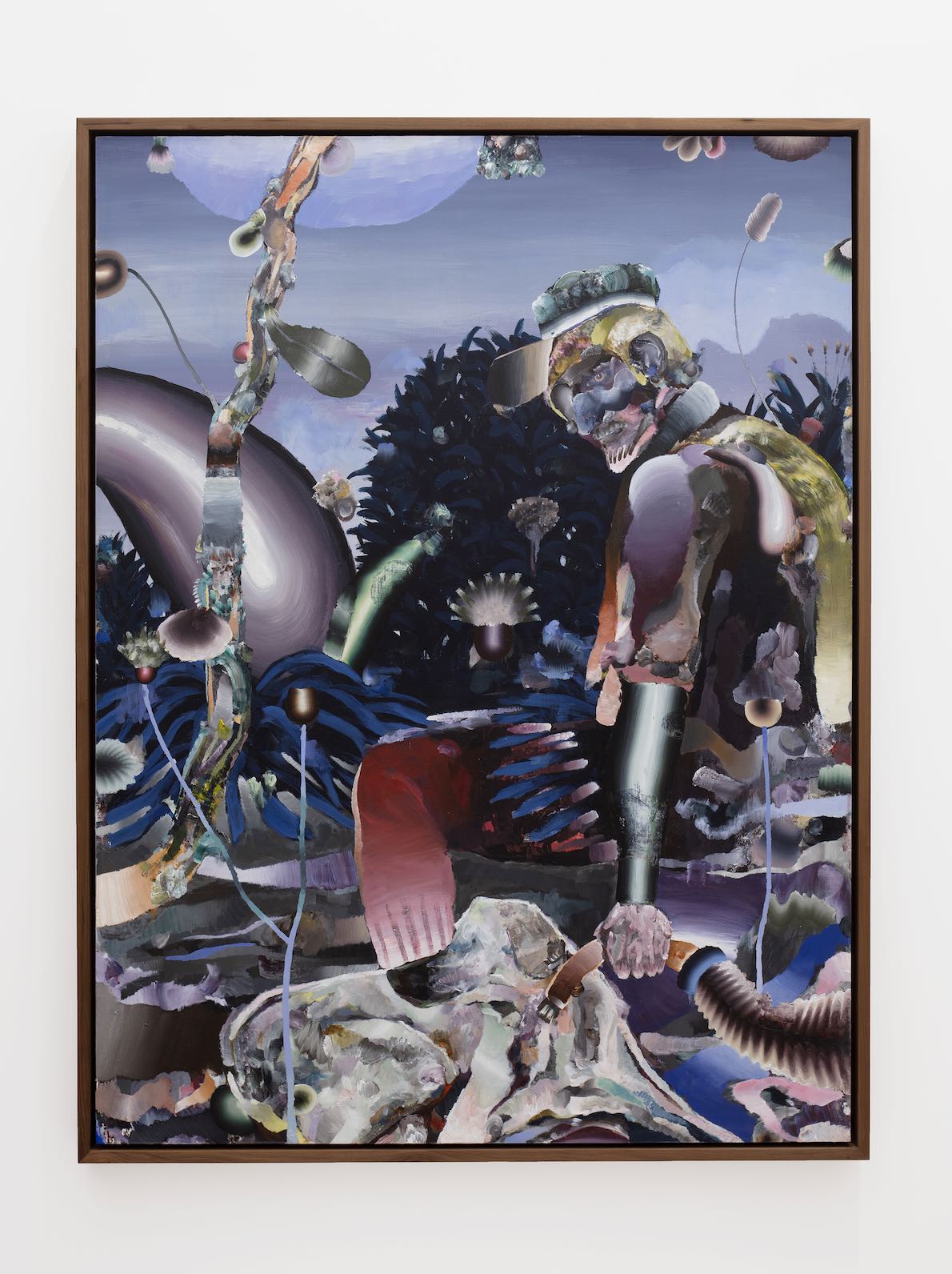

“My family has always walked because nature’s surrounding spaces are abundant, but later they turned into a trail for searching.” Fernando Zarur tells me a story. We find ourselves walking in a desert grassland in the State of Mexico. The gray gradients in the background announce dusk… Organic forms are superimposed on a sky replete with violets and terracottas. I listen to his story, confirming several of the intuitions I had while observing his exhibition Simbiontes, currently being presented at Proyectos Monclova. Landscapes placing us on an eerily close horizon, with nuclear fumes and industrial remains dispersed throughout this air in which we recognize vegetation, animal life, and one or another feral human. Thrown into the future of a poisoned nature, these beings adapt and live together in a toxic environment, rendered structureless by plunder.

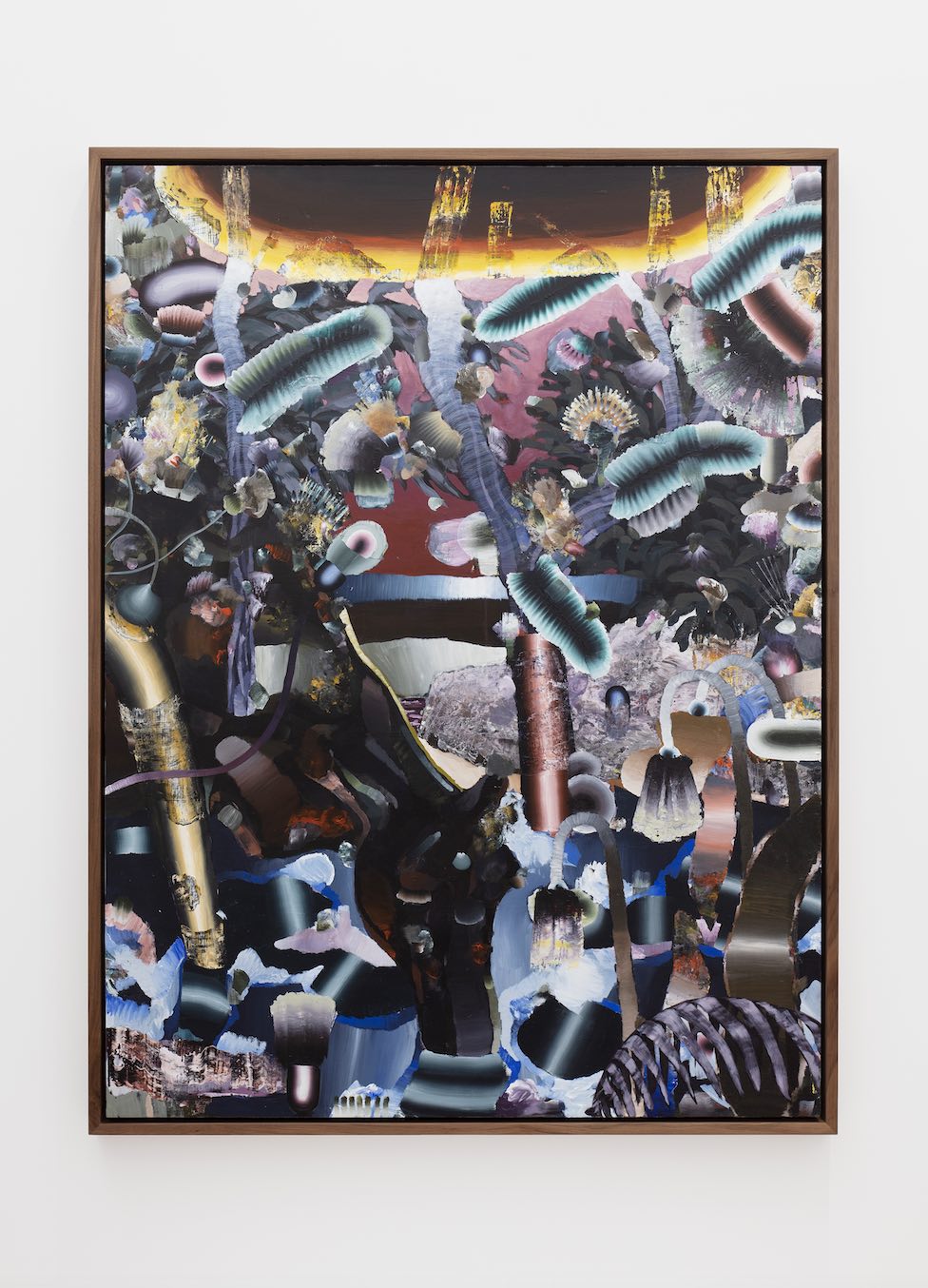

It doesn’t seem exaggerated to assimilate these paintings to dioramas, a kind of Museum of Natural History of the Posthumous Anthropocene. Displayed throughout the gallery are specimens of symbiotic beings. The interstices between kingdoms populate these psychotropic aquariums, in which micro and macro are confused. What story do these industrial fables tell? With what plastic resources does Fernando Zarur generate correspondences between painting and the biotic? Who are they? From where are they looking at us? And what do the symbionts portrayed here portend?

The series maintains an evident formal unity based in palette, composition, and plastic treatments. The sensation of a bestiary displayed across different windows places us looking inside-out at preeminently violet landscapes at sunset or at night. Horizontal fades figure in the background of this stage in which trees, branches, and stones are born; sometimes, an animal emerges from the undergrowth parasitized and populated by lichens and other microorganisms. A few humanoids close to the wild are confused with stones and clown fish. The question arises of whether or not we are under water. Certainly, there’s something suffocating about these motley environments: psychotropic hallucination or nightmare of the Deep Dream?

It was sunset and I went to the jasmine, to pour water on it, to make a bouquet, I don’t know. And from inside the bush I saw arise a hard, dark meat; it had many eyes, which shed tears, which, don’t believe it, immediately became drops of fire.

Translated from La falena, Marosa di Giorgio

Once the horizon has been populated with vegetation, notoriously coupled with the canvas’s bidimensional terrain, there emerge the leading symbionts, which are at one moment camouflaged and at another discernible. The gradients of tone and color differentiate the elements, providing the panorama with metallic accents that recall the cylindrical automatons of Léger or the iridescent peasant women of Malevich. Melancholy beings—made with scraps of fabric (patchwork) or with cans scavenged from the trash—gaze at us with mistrust. And in each fragment there appear the Eyes of God (those esoteric amulets of vibrant colors) sometimes scattered in the air, with no apparent connection, resembling floaters: vision spots. I ask Fernando about his aim in using color gradients. “More than a question of style or fashion, it responds to a need for corresponding to the plastic resources that nature itself uses,” he tells me. Here the effect responds to a specific formal and poetic need.

So who are these beings, and what do they announce? I refer back to 2015, when the Zapatista compas launched an eccentric invitation, “La Tormenta, el Centinela y el Síndrome del Vigía” [“The Storm, the Sentinel, and the Lookout Syndrome”], telling us that a storm was coming, “something terrible, more destructive if it were possible”… And the storm came. Apocalyptic narratives have lost their persuasive power only because reality exceeds them with impersonal obscenity. We no longer notice gutters overflowing with garbage and towns suffocated by greed and indifference; we don’t see that water rises up to our necks and that shipwrecked peoples arrive via our windows…

I think that Fernando Zarur has managed to capture the panorama underlying enthusiastic facades of progress. A flayed reality that leaves the wormy skeleton exposed. End of the Anthropocene—beginning of the symbiotic era and of the biocentric gaze. Paintings, after all, but also mirrors: X-rays of the realm of the survivor.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

*1: Juan Rulfo, The Plain in Flames, translated by Ilan Stavans with Harold Augenbraum (Austin: University of Texas Press: 2012).

Published on May 5 2022