Interview

I didn’t know air had references: A dialogue with Ana Sofía Esteva

by M.S. Yániz

Reading time

10 min

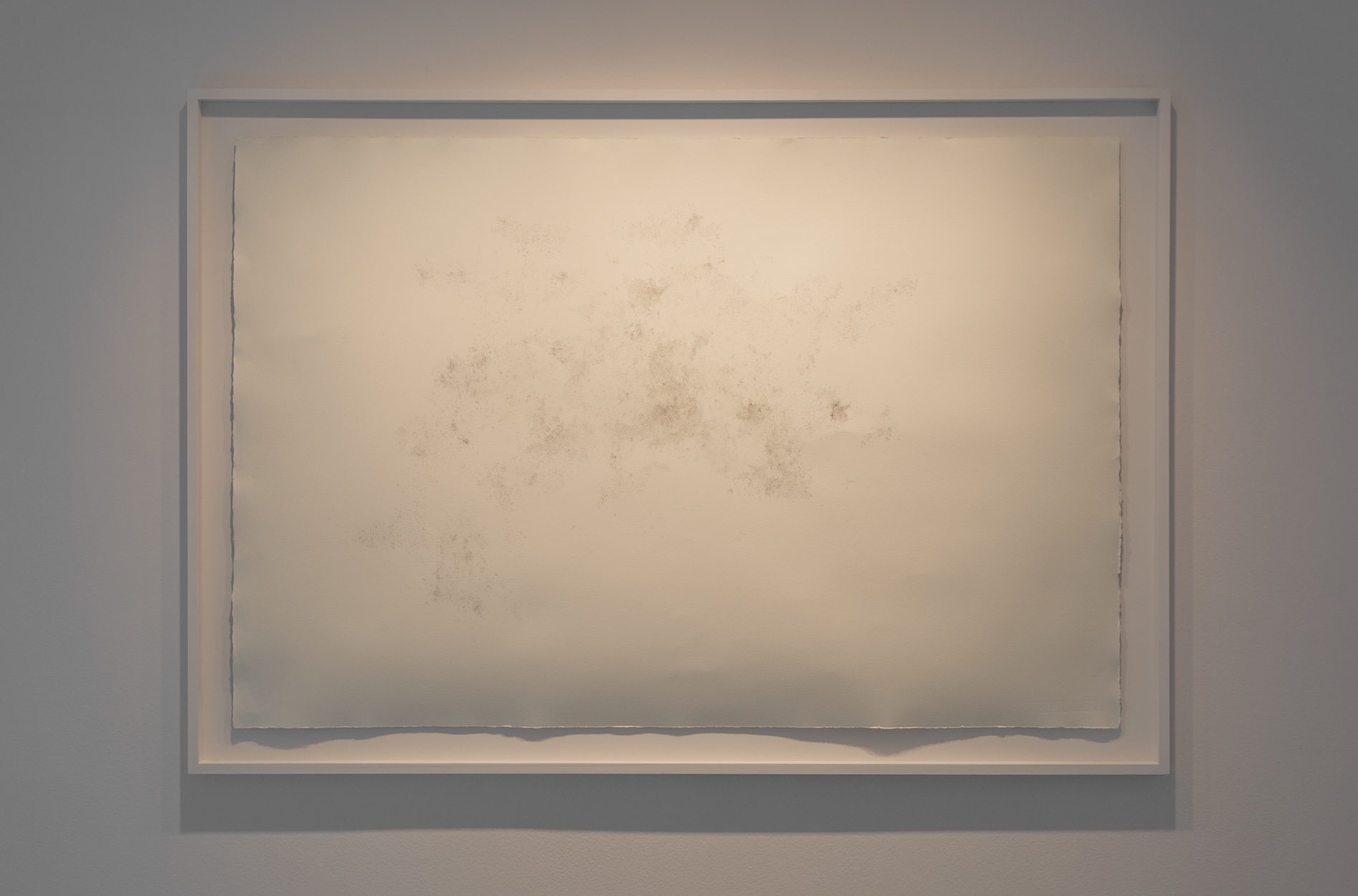

I’ve made my way through this illusory afternoon,

not a grain of this salt recognizes me.

—Olivia Oropeza

Ana Sofía Esteva (Mexico City, 2000) currently has a solo exhibition at Galería Banda Municipal called Como la sal en la comida [Like Salt in Food.] I first became aware of her through an institutional critique project involving the waste and trash (sic) from the Escuela de Pintura y Grabado La Esmeralda, as well as her curatorial research in Mexico. We met for coffee before seeing Chris Kraus in September 2024. Now, in the context of her exhibition, I visited her studio for an interview. Before we begin, it's worth noting that the exhibition itself is hard to describe. There are unframed papers on the walls, barely visible, light dispersions across another wall caused by glass, and encapsulated words on pedestals. The gallery has a large window facing the street, and from the outside, all you can see are different shades of white and some light reflections.

M.S. Yániz: Let's not start at the beginning. Let's start at the end. How did you feel about your exhibition? The place was packed, and people left happy.

Ana Sofía Esteva: Overwhelmed by all the stimuli—it was my first solo show, and explaining the same thing over and over again felt strange. But there’s something very beautiful that happens when you tell people how these objects are made. When I tell them that the glass pieces are filled with the air of words, that I recited poems that filled them. One is from Margaret Atwood, Variations on the Word Sleep, and the words are: “That unnoticed/ That necessary.” Another piece has T.S. Eliot's The Hollow Men: “Between the idea and the reality falls the shadow,” and there’s a Xavier Villaurrutia poem, Nocturno de estatua: “Tocar el grito asir el eco” [To touch the scream, grasp the echo]. I don’t know, it’s at that moment when their eyes open. They see the words in the air, inside the glass. They can’t look at things the same way again. Something clicks, and it makes sense, something they’re seeing here and now. They say, I get it, and those ideas start bouncing around in their minds. I love that moment.

Y: As if there were objects and stories that need to be revealed, and once you’re inside, there’s no turning back.

ASE: Exactly. Or when you see the seven empty drawings from the outside or as you enter, completely blank, and when you get closer, they’re filled with grains of salt. Everyone says, “Oh, it’s like salt or sugar.” They find something.

Y: They see the drawings and then realize that’s where the title comes from: “Like salt in food.”

ASE: And then they no longer have doubts or feel frustrated, saying, “Oh, I thought it was sugar.” You reflect and affirm their certainties.

Y: The exhibition has nothing, but it’s full of emotions—in other words, it’s an empty space that feels very full.

ASE: Almost nothing. I thought, this is... perfect, like it fits so well. It’s too clear, really.

Y: Is that what you’re aiming for? Almost nothing?

ASE: Yes, I think so, definitely. Everything started with Caro Magis. In the production workshop, she asked me if I was familiar with the infrathin and all that Duchampian stuff. I wasn’t. That’s when I got to know it.

Y: Did Magis introduce you to that world?

ASE: I was already using almost nothing and nothing in my work. But yes, I think she led me to words charged with history. The first thing she asked me was if I knew Air de Paris.* I didn’t. I loved it. It was what I was already doing, but I had no idea of the work. That happens a lot in school: you put something out there or do something, and then they tell you how it’s done and that it already has a history.

Y: Is there no surprise anymore? Like everything’s already been done?

ASE: Yes. Or you say, Wow, what a great idea I had! And then you keep thinking, and realize, Oh, this great idea has been around for 50 years.

Y: In this specific case, did you create glass pieces filled with language, just like Duchamp did 106 years ago? Maybe that’s what creation is. I’d never thought of something like that, nor had I seen something like it except for Duchamp. As if forgetting allows for new creation.

ASE: Well, because there are many ways to approach it. Obviously. It’s a completely different thing, but yes. And also, when I was little... Let me tell you something I haven’t shared, I think. When I was little, I asked my parents—for Christmas, I asked Santa Claus—for air from the North Pole. And my dad, I think it was him specifically, did something beautiful: he put a jar in the freezer. When I woke up, he took it out, and when I went downstairs, I saw the jar, touched it, and it was cold. For me, it was North Pole air.

Y: That’s incredible! And beautiful. That’s what art is: bringing other places with just a few tricks. Right?

ASE: Totally. I remember saying, I’m not going to open it, I’m not going to open it, but that same day, I opened it, and it was cold, you know? Like, it felt like they’d brought me a landscape that made sense. I was about seven, I think. It’s one of my best memories.

Y: And what did your dad say when you grew up?

ASE: Well, obviously, after you grow up and learn that Santa Claus doesn’t exist, my dad told me it was one of the strangest things from my childhood. Out of all the things I could have asked for, he never imagined his daughter would ask for North Pole air. But I think it’s one of my favorite gifts. I was so excited because I really wanted air, like cold air from the North Pole.

Y: In a strange timeline between history, knowledge, and personal development, a seven-year-old girl made a Duchamp before Duchamp.

ASE: Duchamp was just a very big kid.

Y: What interested you about that air? The journey of that air? What do you think about it now, having that distant air?

ASE: I didn’t care about the journey. I just wanted to have nothing, I guess.

Y: Your dad was a conceptual artist.

ASE: Totally. Yes, yes, yes.

Y: You mentioned there are other jars. What are they?

ASE: I actually have the original one. (She shows me.) I didn’t include it in the exhibition. For the exhibition, I thought I’d do something better. The first jars weren’t mine; I asked two people for them.

Y: Who?

ASE: A girl. I got one in Lisbon. It was a girl who was talking non-stop about Saramago in a bookstore. She was frantic. “Saramago changed the world, blah blah.” She wouldn’t stop talking. So I thought, Okay, she won’t find it that weird. I had the jar with me, asked her to say a few words into it, she did, closed it, and… that was it.

Y: So you have that person’s breath preserved.

ASE: Yeah. And the other one is from a girl in the Palais de Tokyo. She was also talking a lot, and I asked her.

Y: How did you come to want to trap words in jars? How did you move from the jars of chatty strangers to producing your own pieces? Pieces that are quite beautiful—the work with glass is fascinating.

ASE: I thought, Okay, I don’t want to make any more jars. I want to create something that’s not just about trapping words in jars, but where the object itself has some... life, essence, agency, I don’t know. The word word fascinated me because it’s a thing that defines itself; it’s its own definition. I wanted to create the object-word, referring to words. It felt like an absurd… what’s the word? An absurd abyss. So I was really caught up in that, and I think one of the exercises that felt most natural was trapping them.

Y: You literally wanted to have the words…

ASE: A spoken word—how do I touch it? Yes, I want my spoken word. I also did a lot of things with text, but then I thought, No, I see it. Paper and ink.

Y: And wasn’t there enough materiality in language? Maybe it was too immaterial. Just ink, so present and insignificant.

ASE: That’s how it is with written words. It bothered me because typography gets in my way a lot.

Y: What font do you use?

ASE: Depends on the text. But anyway, typography really gets in the way.

Y: But what does it get in the way of? I mean, do you think there’s neutrality in words? Would you seek some sort of neutrality?

ASE: I don’t know, yes. Yes, but it doesn’t exist. I know it doesn’t exist. But yes. But it’s like the abstract idea that thinks everything is language. Because if it’s not a written word, it’s my voice, with my tone, my accent, whatever, saying it. It always materializes in a context, in a subject. Yes. There’s no such thing as a word in itself.

Y: In another one of your pieces, the ones without salt stuck to them, you draw clusters of salt. They seem so precise, realistic would be the word.

ASE: Do you want to try?

(We begin drawing salt or clusters of salt, and I start making some sort of order or series that doesn’t resemble salt at all.)

Y: How do you map instability? I mean, in your drawings there’s a chaotic principle, a chaos that actually produces beauty. It’s very difficult, but in your drawings, it really seems like salt or dust fell, and it’s not just a representation. Do you know what I mean?

ASE: I was interested in dust and salt. At first, I started from a mental image, and everything was very ordered. Then I had to start copying dust, literally. Also because I didn’t want to draw "things" in class. That’s when I realized that when dust falls, it forms clusters, some bigger, some smaller; they tend to have different distances between each other. They’re not evenly distributed. Chaos looks more ordered, but I can’t think about that when I’m drawing. Because when I draw chaos, I’d say: “That’s too ordered.” So, I try not to think about chaos as an idea because I end up organizing it, and it no longer looks like either order or chaos.

Y: It’s like entropy—something about the morphology of things arranges them in their places, wherever those might be. Was your exhibition always intended to be about chaos and salt? How did your show at Banda Municipal come about?

ASE: No, interestingly, I was going to start with another project. When the curators at Banda Municipal invited me, they were thinking of a different kind of exhibit. Something like an act of darkness... I mean, what I initially showed them were drawings and this branch here, for which I knitted a sweater. I was imitating the logic of the root with the embroidery. That was the idea, but when I started production, interestingly, everything I was thinking of and started to create was transparent or white.

Y: And how did you go from the darkness of the knitted tree to something transparent or white?

ASE: Because the first thing I wanted to include was the words.

Y: And there’s not a single word in the exhibition.

ASE: Oh, yeah. Though maybe there’s a lot of language, after all.

Translated to English by Luis Sokol

*https://www.centrepompidou.fr/es/ressources/oeuvre/cbLy77k

Published on January 17 2025