Essay

Mom’s Kiss: Alonso Robles at Interior 2.1

by Alejandra Carrillo

On that excessive and impetuous faith characteristic of women in our homes

Reading time

5 min

That’s why they’ve learned to grow flowers

and to sing their sorrows well,

and have invented the best works

and the best instruments.

That’s why they understand art

and know how to find it wherever it might be,

even if there isn’t any

(of which there always is).

Gata Cattana

Among the working class the only thing we ever inherit is work. And I’m not referring to a job, position, office, or appointment, but rather to the idea of work, the very opposite of nepotism: the hope for a better place. With luck, we inherit a trade, an iron will, a sense of guilt, and the fear of hunger. We inherit our siblings and aunts, our grandparents. They teach us that sometimes the family is all you have, and sometimes that’s correct. We also inherit a piece of faith, since faith and work are for us always intertwined.

Even if there’s no God, my mother has many times led me to believe. I don’t know exactly how it works, but I swear there have been days when I felt that it was her blessing as I was leaving home that led me to return. That faith, I’m certain, deserves a monument: a tribute not to God or to the martyrs or to the virgins, but to our jefitas—to the grandmothers, to the neighborhood itself that, despite everything, has not yet seen us die.

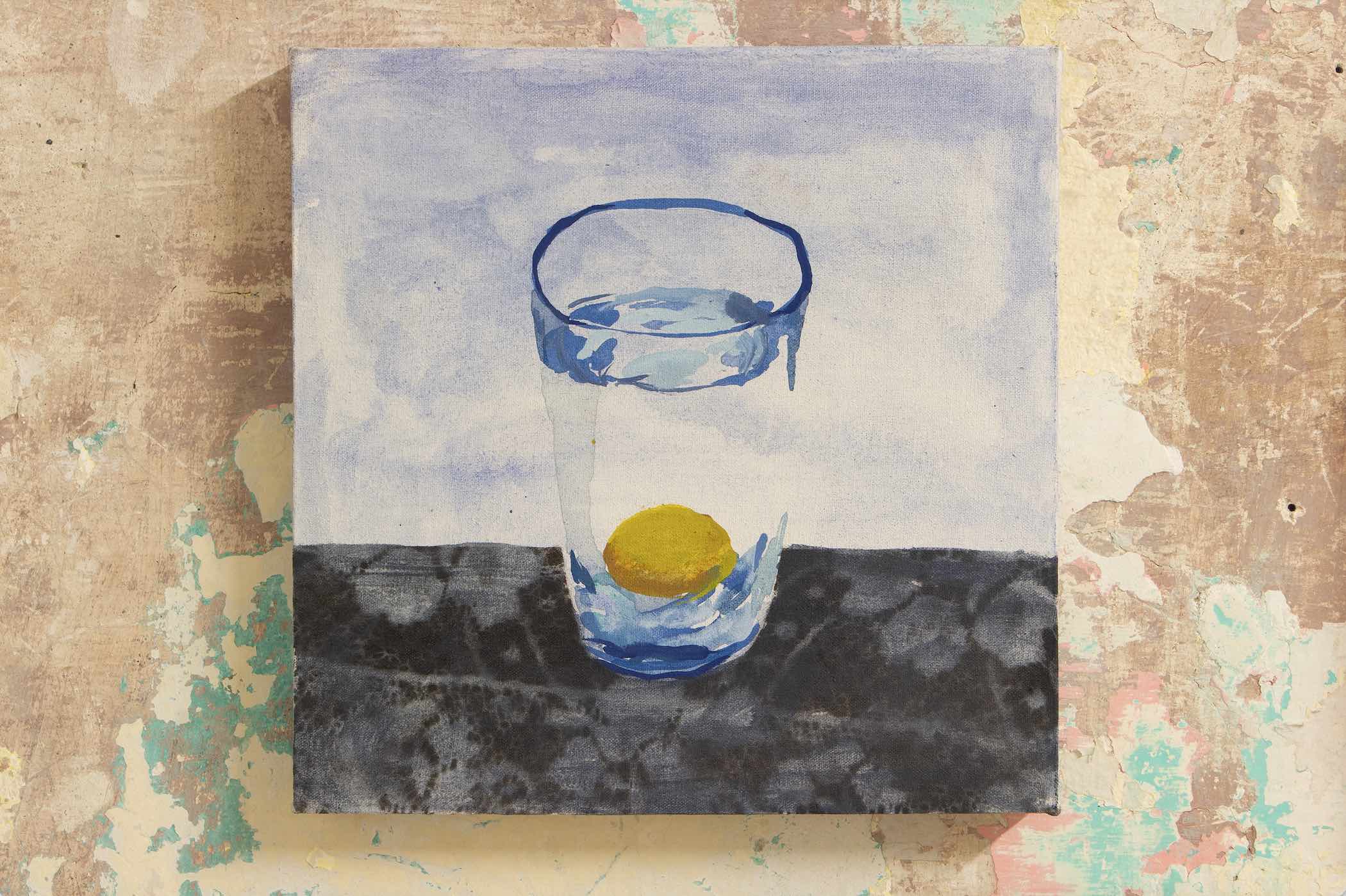

That excessive and impetuous faith characteristic of women in our homes is of special concern to Alonso Robles (born in Ciudad Juárez in 1998) in the paintings making up the exhibition Se tiene fe mientras se llena un vaso [One Has Faith While Filling a Glass] at Interior 2.1, curated by Bruno Enciso. I believe that the sign of the cross has also made him feel calmer in the face of fear and distress.

The paintings in this series are portraits of various protection devices that might not work, but that are employed anyway because you never know: a fearful dog guiding an entrance, jugs for preventing stray dogs from peeing on the sidewalk, bags of water meant for protecting against flies, and glasses with eggs used for spiritual cleansing.

Within these simple objects—which also speak to the daily transitions we make from outside to inside the house without knowing what we’re taking with us—there’s something even more immense, namely that care work into which his mother and grandmother placed all their faith so that nothing would happen to him.

There are many ways to protect a house when you can’t move and you live in the city that for many years competed for the title of most dangerous in the world, even though for those of us who come from outlying neighborhoods designated as dangerous, going out, despite everything, might not have felt like Russian roulette, even if it was. These women made us feel protected. They gave us that strange and unnameable something, letting us go out every morning thinking that we would not be touched. A leap into the void, a sense of belonging—naive if you will—but perhaps above all, the need to work, that inertia of our lives’ machinery that doesn’t stop for anything. One has to work.

We went out thinking that something protected us: not a private condo, not a gated community with a guarded entrance. Not a last name, not a prestigious school, not powerful friends or relatives who could pull strings. Not weapons, not armored windows. Perhaps a poorly made wall with pieces of glass inlaid in the concrete, a very high iron railing, and at most a menacing dog. Our moms would protect us, genuinely believing that we deserved another world.

And for Alfonso and his siblings it worked; for my siblings and me it worked. We remain alive. We were certainly lucky, we felt protected, though we don’t really know why. We would suckle that faith that went beyond belief. A faith that’s proof of everything since it doesn’t expect a divine reward following death in exchange for an earthly sacrifice (renouncing sins, going to mass, abandoning pleasures and wordiness), but is instead a random and absolutely irrational sense of faith. What these women believe in is so powerful that it doesn’t need an understanding that’s shared with and endorsed by an institution. God/It/Their Faith will protect us from “up there,” even if we don’t deserve it. A silent prayer in the midst of uncertainty. A “pray for us” faith that sometimes, without explanation, repels overdoses and bullets.

That’s why, even if we don’t believe, we entrust ourselves to the Virgin of Guadalupe, we send pleas to the Virgin of Zapopan, or we make the sign of the cross, without anyone seeing us, just before going out on our nights of glory. Even if there’s no God, my mother has many times led me to believe. Because that God whom I’ve never seen and whom, when the time comes, I would deny three times if asked is much greater than dogma: it’s mom’s kiss.

Alonso’s work in this exhibition is a portrait of one’s home; it’s a way of honoring that kiss as well as ensuring its presence. We see that kiss as close not only to his life but also to his artistic practice. And what other faith would we want than one that leads us to continue dedicating ourselves to art, despite all laws assigned to our lineage?

The exhibition Se siente fe mientras se llena un vaso by Alonso Robles (born in Ciudad Juárez in 1998) is on display at Interior 2.1 until August. To attend you must make an appointment via Instagram: @interior2.1.

Published on July 23 2022