Review

Mnemósine by José Eduardo Barajas at Proyectos Multipropósito

by Eric Valencia

Reading time

5 min

Mnemósine does not have a dominant theme. In the guided tour that its author, José Eduardo Barajas, offers me, he is very careful in constructing a discourse that does not privilege any one of the facets that motivated the exhibition. He presents it rather as a framework that’s built with reflections arising from his practice as a painter, his readings and academic references, his experience with technique, and his personal life.

The exhibition is titled Mnemósine, like the female titan, and like Warburg’s atlas. Memory as the guiding axis, to the memory of his sister Aurelia, from the memory of the experiences he shared with her, but also as a spell of forces that are being built in the frantic production process of the 625 paintings making up the exhibition.

The ceiling panels of Proyectos Multipropósito provide the works’ support and are exhibited mounted on the aluminum grid dating from when the space was a call center. Barajas takes advantage of this order as a reminiscence of a certain way of storing information and memory, such as the grid of the photographic roll on the cell phone or the order of posts on Instagram. He uses this structure to organize an evasive and complex narrative, a saturated one, which invites the viewer to produce his own routes, his own organization.

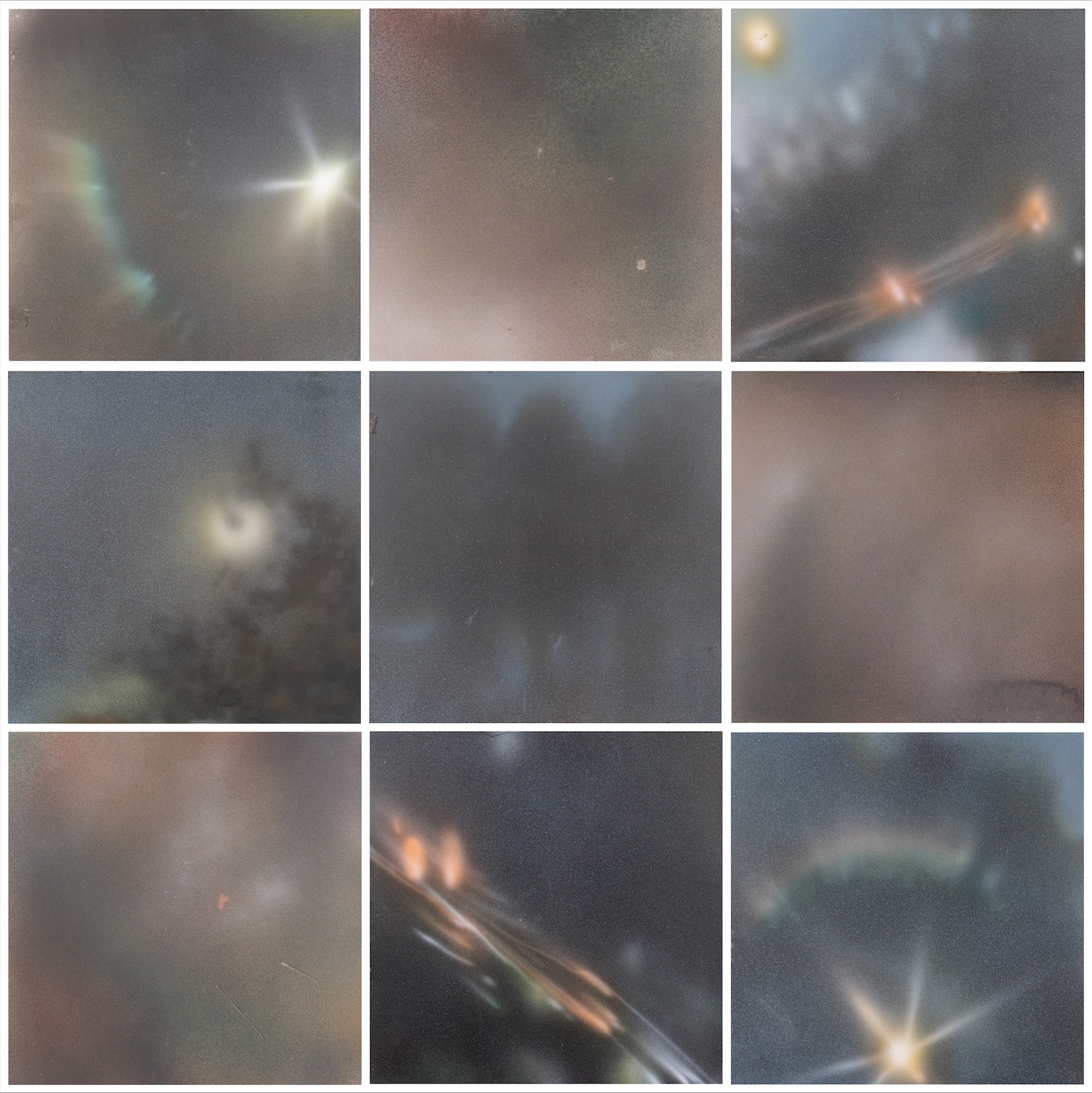

Barajas works each panel with acrylic applied using an airbrush. He constructs each painting with his own version of the Venetian technique: by accumulation of layers that are sometimes translucent and at other times opaque. He starts from a dark background upon which he builds light and color. From a certain moment on, he begins to take advantage of the indeterminate quality of these backgrounds in order to use them as stimuli for his memory: “I did not want to approach the image from a preconception, but rather to find something in the ambiguity of the mark, through the mark.” He even includes several paintings completed at the time of the process in which the layers have not yet formed recognizable scenes; they appear as abstract environments, almost monochrome. He distributes the pictures in the composition, using them as “pauses,” in areas where he felt there was “excessive information.”

_amp_p_36_(1).jpg?alt=media&token=1456bae6-bbed-4043-900a-682caaa91a47)

The first large block of images that we find upon entering is a scene built with forty-two panels in which the tops of some trees are represented, crossed by sunlight and seen in a low-angle shot. It’s the most distant memory that he could evoke in the company of his sister.

Beginning with this first group of works, Barajas decided to work in a more fragmented way. With some exceptions, the scenes are now represented in a single frame, albeit gathered in sequences in which figurative motifs—such as plants, waves, a sail—as well as pictorial motifs— such as color palettes or types of contrast—are repeated.

The artist tells me that beginning with the first large block he maintained the same lighting in groups of large works, strips that go from south to north in which he moves the light from different times of day, thus corresponding to the actual movement of the sun above the gallery. They begin in the east, with a morning light, and advance towards the night, in the west of the gallery, to end up in the northwest corner, where scenes of a dawn (in a small group) can be distinguished. It is a double movement that fragments the scenes into frame-units and, at the same time, creates a great narrative that encompasses the entire exhibition. Nevertheless, one area leaps from this logic, beyond the night: at the western limit of the exhibition space, we find a line of abstract works.

In his guided tour, Barajas refers to a method with which he has been working for a long time. As we flip through his publication titled Sky,* he explains to me: “The pink is a face; it’s a face, and then only pink.” First he establishes an association between elements: “The pink is a face…,” then he performs a sequence in which it is repeated, thus producing combinatorics until they are exhausted. “The pink is a face; the pink is a face…” Upon reaching the combinatoric limit, the association is broken: “The pink is a face; it’s a face, and then only pink.”

In the previous paragraphs I have wanted to describe how this method occurs at different moments of the exhibition, as well as how a type of non-figurative painting, one that is almost monochrome, emerges from them. It’s the “only pink” of this method, which is mounted on the exhausted series and is then detached from it. It’s never, by any means, just any pink. These paintings are no longer the figuration of memory, but rather the very event of remembering: embodied, turned into an image. At the limit is the object that exclusively concerns each field, each practice, or each faculty. At the limit of representation appears the image. And it is, perhaps, at the limit of memory where we can remember what has not been lived.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

*:Barajas, J. E. (2018). Sky. Vacaciones de trabajo.

Published on May 4 2023