Review

Memories of a Filmic Shadow at 'Limbo Óptico' by Daniel Monroy Cuevas

by Andrés Ardila

At Laboratorio Arte Alameda

Reading time

7 min

Shadows, nothing more

Between your life and mine

Shadows, nothing more

Between your love and my love

José María Contursi

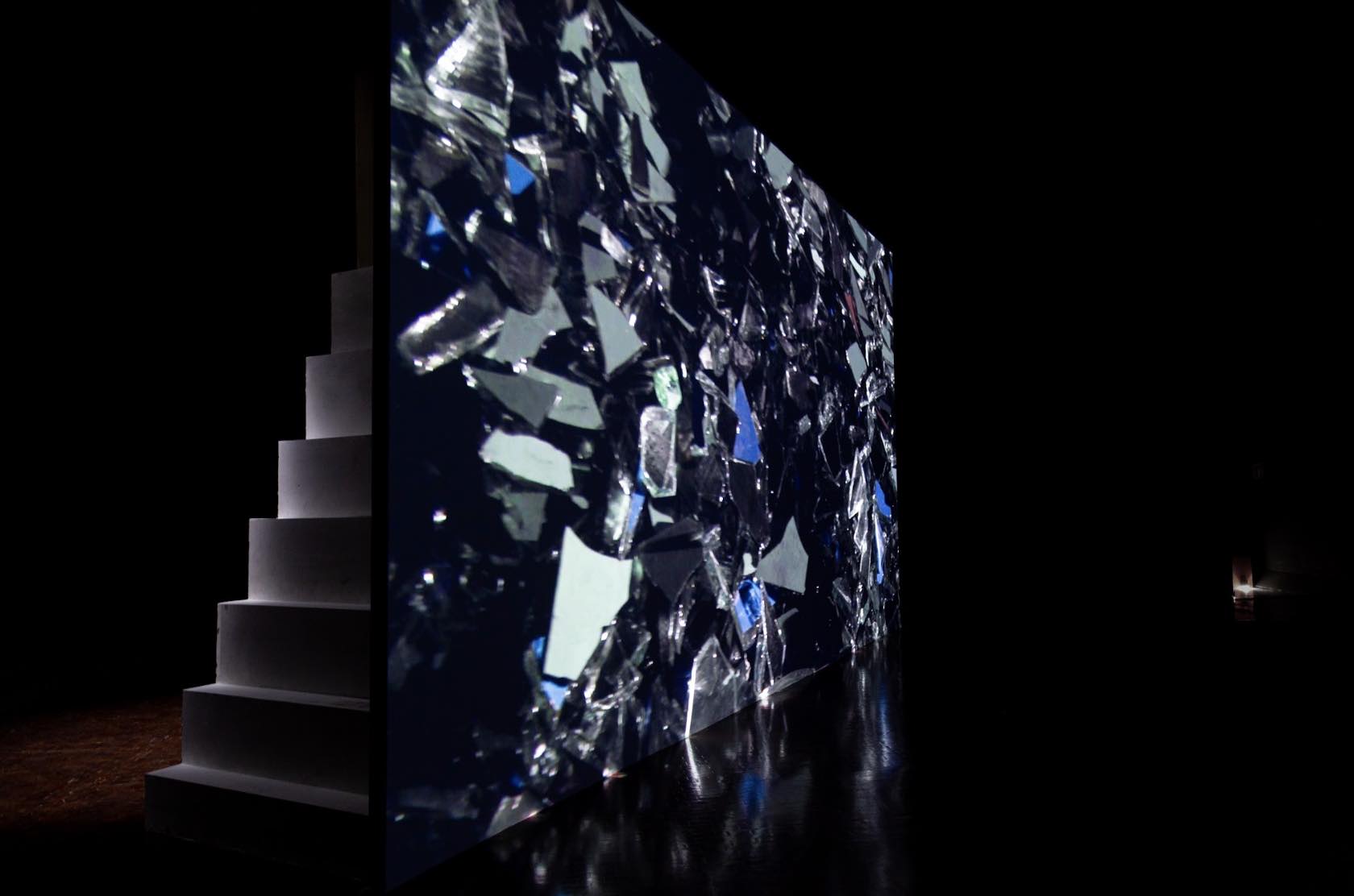

After going through several corridors, one enters a dark room at Laboratorio Arte Alameda in order to see “La hora en que las sombras se proyectan” (“The Hour When Shadows are Projected”), the first chapter of the installation Limbo óptico by Daniel Monroy Cuevas. When one’s already inside, the lack of light can be a little blinding. The gallery’s guards help by lighting the way. From the entrance, a large structure is observed that has some stairs painted white as well as some bare wooden parts, all compacted into a large volumetric rectangle that on one side is a film screen; there are seats in front, available for sitting down if one wants.

The video shows an adult man with a beard, a little scruffy, who is in a kind of limbo where he interacts with some objects, mainly a large white staircase. The man waits there seated on the stairs, walks on popcorn, organizes his shoes, and sometimes interacts with tiny stairs that fit inside the large staircase in an almost Escherian gesture (a staircase going towards another staircase, creating an optical endlessness). In some key moments the video’s music is accentuated, as kinds of strained sounds build up an atmosphere. Then, some shadows in the shapes of bodies occupy the white of the stairs: it is as though they were chasing the man trying to cover both the whiteness of the space and his body. Light, shadow, and body as essential elements of the cinematic.

In Daniel Monroy’s work there is an interest in reflecting on the time of the medium via transforming images into objects. That is, a story, an anecdote; or rather, the film itself becomes an object. This is what takes place in Espectador en el vacío (“Spectator in the Void”), in which a series of magnetic tapes, recorded with the highest light saturation, are compacted and sanded in order to create stones. In this process, the fiction, the process, the narrative, or the contained image vanishes. Why does Monroy seek this de-fictionalization of the image? What is entailed by the gesture of vanishing one’s own object of study, and leaving nothing but its minimal elements?

The video’s protagonist is a structure: a set of stairs. It is a setting that is at the same time the scenery of a video recorded in the same space, of the exhibition and the screen, where it is projected. A staircase that is compacted and that is itself an object of the installation. An object that astonishes by its size and that contains all the temporalities and traces of that cinematic production, but that at the same time expresses the history of those filmed objects. An endless number of memories, or accumulations of shadows.

How many staircases are there in film history? Some are gigantic stages upon which descend musical stars while singing some ballad, while others belong to to Shakespearean lovers confessing their passion. There are those of suspense, persecution, or terror: marks of a distressing urban life. Nevertheless, there is another type of staircase on which public life and violence converge, exemplified in the extremely famous scene of the Odessa steps in the Russian director Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925). This silent film depicts a violent scene in which the tsar’s army goes against the Russian people on a long staircase in the town of Odessa (now in Ukrainian territory). It is famous not only for its subject, but also for its form. The scene is a compelling example of the filmmaker’s own theories, which have been highly influential in film schools around the world as a major reference point for the formalist theory of montage. According to Eisenstein, just as in Chinese pictograms where one ideogram plus another means something totally different, montage can express new meanings by joining discontinuous images. For example: “a dog + a mouth = to bark.”*1

In this way, the most disturbing thing is the presence of those shadows accumulating on the stairs, defying the man’s very existence in them, covering the light that would otherwise allow us to see him, lurking as though disposed to violence or terror. That’s why they remind me of the Odessa steps (or maybe vampire movies, or also Hollywood film noir detectives). The stairs are then a metonym for who ascends or descends, and thus a representation of class struggle, but in its most abstract form: their whiteness and weightiness in this scene permit these types of associations. The fiction is then left to the viewer of the work, who thus supplies their meanings according to what they have in mind, their images or memories. A staircase as blank canvas.

Another fortuitous relationship came to mind when at one point in the video the man dirties the white stairs with his hands, depositing the passing of his fingers as marked by dirt or dust. In his controversial performance Mugre (“Dirt”), the Colombian artist Rosemberg Sandoval takes a homeless person in his arms and carries him to Cali’s Museo de la Tertulia, where he paints the walls and a white canvas with the dirt that the guy’s clothes have accumulated. How many homeless men are there in Latin American movies?… Rosemberg wrote about his performance:

Dirt (mugre) from another universe, from another world, is what documents my sick way of drawing on the walls and the impeccable floor of the Museo de la Tertulia, using a miserable man picked up in the street, used as instrument and as essence, tying together a connection: art-dirt-life. […] This de-staging, of course, has a prelude consisting of the displacement of the performer-(assistant) on my shoulder from his place of settlement to the inside of the Museum. *2

The video, on the other hand, does not represent the displacement of a real character to the gallery, though it does keep this man-actor locked into the image, in limbo, staining the whiteness of the walls, all while the montage inserts details of popcorn and some broken glass—perhaps as a critical commentary of film and its spectacle.

The curatorial text announces: “In this constantly changing exhibition project, the second and third chapters formulate different movements towards the dissolution of the film. […] With inescapable persistence, each chapter accelerates towards abstraction.” Finally, I turn my gaze toward the living room floor painted a reflecting black, and I then see the blurry film screen. I walk upon the floor in order to leave the gallery and I thereby also cast my shadow: a screen as a producer of light, a spectator leaving his mark on the space.

“La hora en que las sombras se proyectan,” part of Limbo Óptico, will be open until January 8. The second chapter will take place from January 14 to February 19, and the third from February 25 to April 9 at Arte Alameda.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

1: Sergei Eisenstein, Film Form: Essays in Film Theory, edited and translated by Jay Leyda (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., 1949), 30.

2: Sandoval, Rosemberg. Mugre en Festival de performance de Cali-Colombia (Helena producciones), 57.

Published on December 19 2022