Review

Memories of Two Exhibitions | Yolanda Ceballos and Gwladys Alonzo

by Othiana Roffiel

At Galería Hilario Galguera

Reading time

6 min

In 2013 Yolanda Ceballos (Mexico, 1985) stumbles upon a plot of land in Monterrey; on it lies the remains of a house that has just been demolished. At this time, Yolanda is considering leaving her career as an architect.

In 2015 Gwladys Alonzo (France, 1990) spends the summer working as a guide in a bunker in Saint-Nazaire, a town on the west coast of France abounding with shelters built during the Second World War. At this time Gwladys’s mother is living in that same city.

From that day on, Ceballos starts keeping a record of every plot she encounters containing collapsed buildings: one hundred eighty to this date. More attracted to destruction than to construction, Yolanda eventually quits architecture. Currently at Galería Hilario Galguera the artist, originally from Monterrey, presents Cinco de septiembre de dos mil dieciséis. Terreno #42 [September Fifth, Two Thousand Sixteen. Plot #42], a solo show that takes inspiration from her discovery of the aforementioned piece of land. In the last few years Yolanda has returned to that terrain five times.

After those months in Saint-Nazaire, Gwladys visits Mexico for the first time—she spends her twenty-fifth birthday in a shabby hostel in Torreón. Years later, she again comes across a bunker, only this time it is not a war shelter located in a French city, but rather a vault in the San Rafael neighborhood of Mexico City. This spot, which once served as the safe of a jewelry factory, is now an exhibition space known as “the bunker,” and currently houses one of the two parts of Alonzo’s solo show, El vicio del peso [The Vice of Weight].

The bunker* is found within what is now the Centro Cultural Rosas Moreno 68, located just around the corner from Galería Hilario Galguera, where Alonzo’s exhibition continues on the terrace. To get to Alonzo’s show, one has to pass through Ceballos’s. Although the two exhibitions are independent, inevitably the memory of what is experienced in one is carried over to the other.

The sun is about to set on the roof of Hilario Galguera. I find myself among six sculptures by Alonzo; several of them resemble the pieces being exhibited in the bunker, but the way that my body travels through this space is totally different. Here the works become part of the environment, existing in tune with the trees, with the sky, and with the roof terrace’s architecture. I feel relief.

In the confines of the bunker, the sculptures not only felt cloistered, but also took on a life of their own: the concrete bodies pounced upon my own body. I was in the bunker for five minutes (it felt like twice that amount of time) and on the roof of Hilario Galguera for thirty minutes (it felt like fifteen).

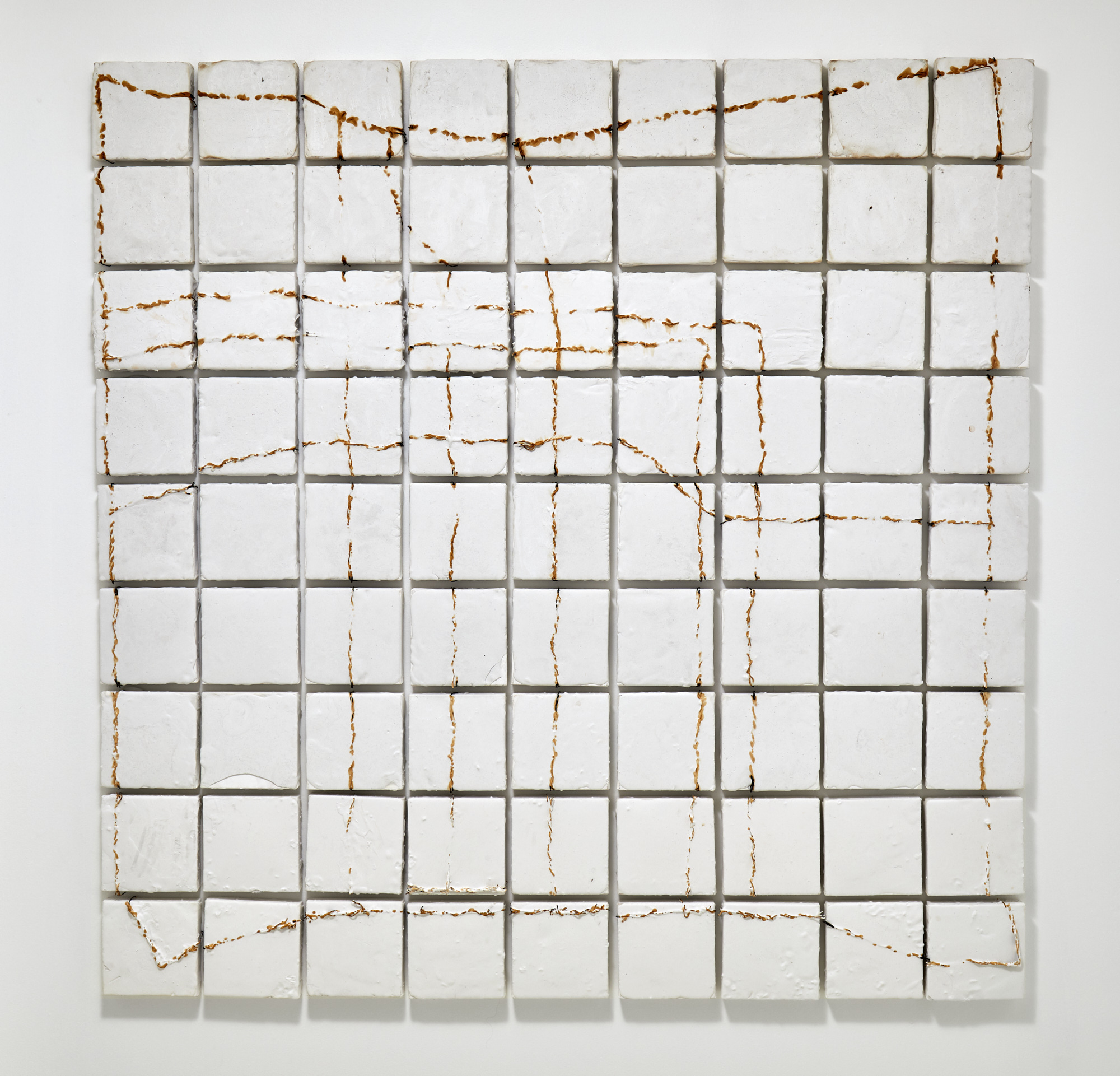

I now think of Ceballos’s fourteen pieces located in the rearmost area of the gallery (it was the last thing I saw before continuing up to the roof). The work of both artists is highly material; its corporeality is undeniable. The pieces make demands upon the body: to stop and to move, to close in and to back away, to tense up and to relax; they call upon the space: to welcome them and to reject them; they exact things from time: to be in transit and to stop. Both Alonzo and Ceballos construct their works with virtually the same elements: rebars and a mixture of white cement and marble powder, materials that record the passage of time in very peculiar and poetic ways. These materials acquire their character after being exposed to different environmental and temporal factors, and although they might undergo changes in color and texture, they do not thereby lose their strength.

In Ceballos’s pieces the white of the cement predominates and color only emerges with the passage of time; in the case of these fourteen pieces, the stagnant water at the base is gradually absorbed by the cement, resulting in a subtle tonality change. In contrast, most of Alonzo’s sculptures are of different colors, created from the cement pigments with which she dyes the mixture.

The essences of these two artists’ bodies of work are different and their pieces come about in distinct ways. For Ceballos, concrete—which, when exposed to water, further hardens over time—acts as memory, ever changing. Ceballos converts physical blueprints into mental ones; she erects works of art from debris. Her pieces transform before our eyes (for example, as the result of the oxidation process of wire immersed in plaster); however, this takes place at such a slow pace that the change is imperceptible to the eye and will manifest itself only after months. If in the future I again converge on one of Ceballos’s pieces, it will most likely look different. What I saw that day will only live on in my memory.

The way that Alonzo approaches this mixture of concrete and marble powder is different from that of Ceballos. For Alonzo this paste is simultaneously abrasive, buttery, sticky, disgusting, and seductive. She manipulates it as though it were a very serious game; she splatters it, she smears it. Forms are born in constant tension: simultaneously rigid and flaccid, undoubtedly phallic; they are uncomfortable and playful, they beguile and they repel.

While for Ceballos this cement mixture is a metaphor for memory, for Alonzo it is something much more visceral; it is cake frosting or shit. Yuck, how delicious! In Gwladys’s work time passes differently than in Yolanda’s: Yolanda’s pieces seem to sway between past and future, their poetry found in their capacity to come into being in time, while Gwladys’s unfold in the present.

I would like to remember every peculiarity of Cinco de septiembre de dos mil dieciséis. Terreno #42 and of El vicio del peso; I wish I could describe every recess of every piece, what I was thinking while immersed in the claustrophobia-inducing bunker with Alonzo’s works, or enthralled in front of the overwhelming white of one of the wall pieces by Ceballos; but there are things the mind forgets. However, through a multitude of sensory and physical impressions, my body returns me to those memories.

Could it be the vice of remembering?

*The bunker is open by appointment only.

Published on Oct 23 2019