Review

Body Memory | On Maya Goded, Laia Abril, and Nan Goldin

by Nicolás García Barraza

At the Centro de la Imagen

Reading time

6 min

The year 2019 has witnessed an energetic rise in protest against the gender-based violence that has so withered this country. Every day the figures become more worrisome; the discontent has been embedded in the marble of those monuments that cause such distress. The social rejection produced by painted graffiti leaves the impression that Mexico neither understands nor takes a moment to reflect on its urgent and necessary social transformation. As Gloria Steinmen says in her book My Life on the Road: “We might have known sooner that the most reliable predictor of whether a country is violent within itself…is not poverty, natural resources, religion, or even degree of democracy; it’s violence against females.” A city that is sinking—something rooted in the collective imagination and in the systematic violence that has so avoided any change in direction—watches as women rise up. Women have (re)affirmed themselves as a symbol of courage and resistance.

In visiting the series of exhibitions at the Centro de la Imagen I could not help but think that the Bienal de Fotografía arrives at a key moment for the city. The recognition and dissemination of the work of women photographers—within a panorama historically taken up by the straight, white male—functions as a declaration before a situation not contained by the exhibition hall. The biennial also reveals the failed patriarchal system that wears us down and makes such a show necessary, when in a more just world there would be no need for such an emphasis. Women (re)claim their position in contemporary art and regain control of a narrative that for years focused on silencing and minimizing their work.

Maya Goded, Laia Abril, and Nan Goldin are three of several photographers exhibited at the venue; their work allows us to observe how the stigmas and limitations that patriarchy has imposed on society have in turn unleashed a sharp rejection of feminism and gender ideology.

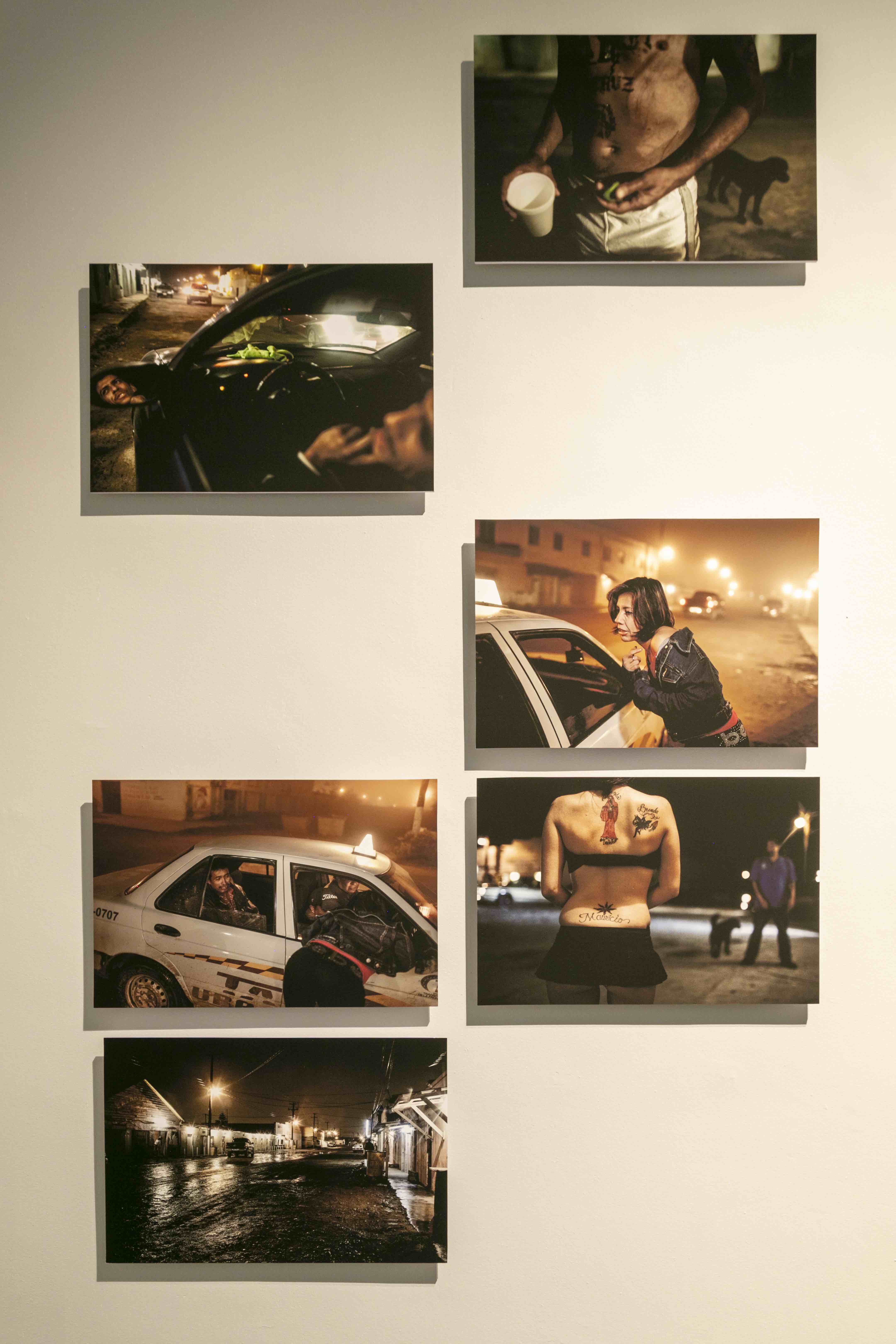

Welcome to Lipstick illustrates the oblivion and decay of the red zone located west of the city of Reynosa, Tamaulipas. Maya Goded shows the reality of a town that was initially thought of as an area designated for the sex trade, where there would supposedly be in place protections and health regulations for women engaged in sex work. It turned out to be the opposite.

The photographs reflect the relentless violence that has caused drug trafficking, migration, and machismo, just as it also portrays the damage that state power and control have occasioned in the lives of women who struggle day-to-day to survive in a profession that profits from their bodies, a profession that remains “hidden” under the gaze of a “decent” society. Goded’s work not only continues her extensive reflection on female sexuality and prostitution; it also fulfills an educational and recording function, offering a historical archive for problems that do not just belong to the past or to the present, but rather, if not worked-through, could be prolonged into the future.

On Abortion by Laia Abril is part of the visual investigation titled A History of Misogyny. In her first chapter, the artist documents and conceptualizes the repercussions of lacking access to a fundamental right: the right to abortion. Charlotte Jansen describes the work as “impossible to erase from your conscience once you’ve seen it.”[1] Abril emphasizes the importance of including abortion in art history, just as Tracey Emin had done in Terribly Wrong (1997) and Paula Rego in Untitled: The Abortion Pastels (1999). The Spanish artist presents a rigorous compilation addressing the stigmas and taboos that have deprived women of their corporal autonomy and of their freedom to make decisions regarding reproduction. The installation’s guiding thread consists of the stories of several women who have had abortions. Abril emphasizes the psychological and emotional complexity surrounding the procedure, as in the case of a Chinese woman who suffered a forced abortion at eight months pregnant. The show, which is sometimes painful to witness, reminds us how essential it is to offer safe and legal access to abortion.

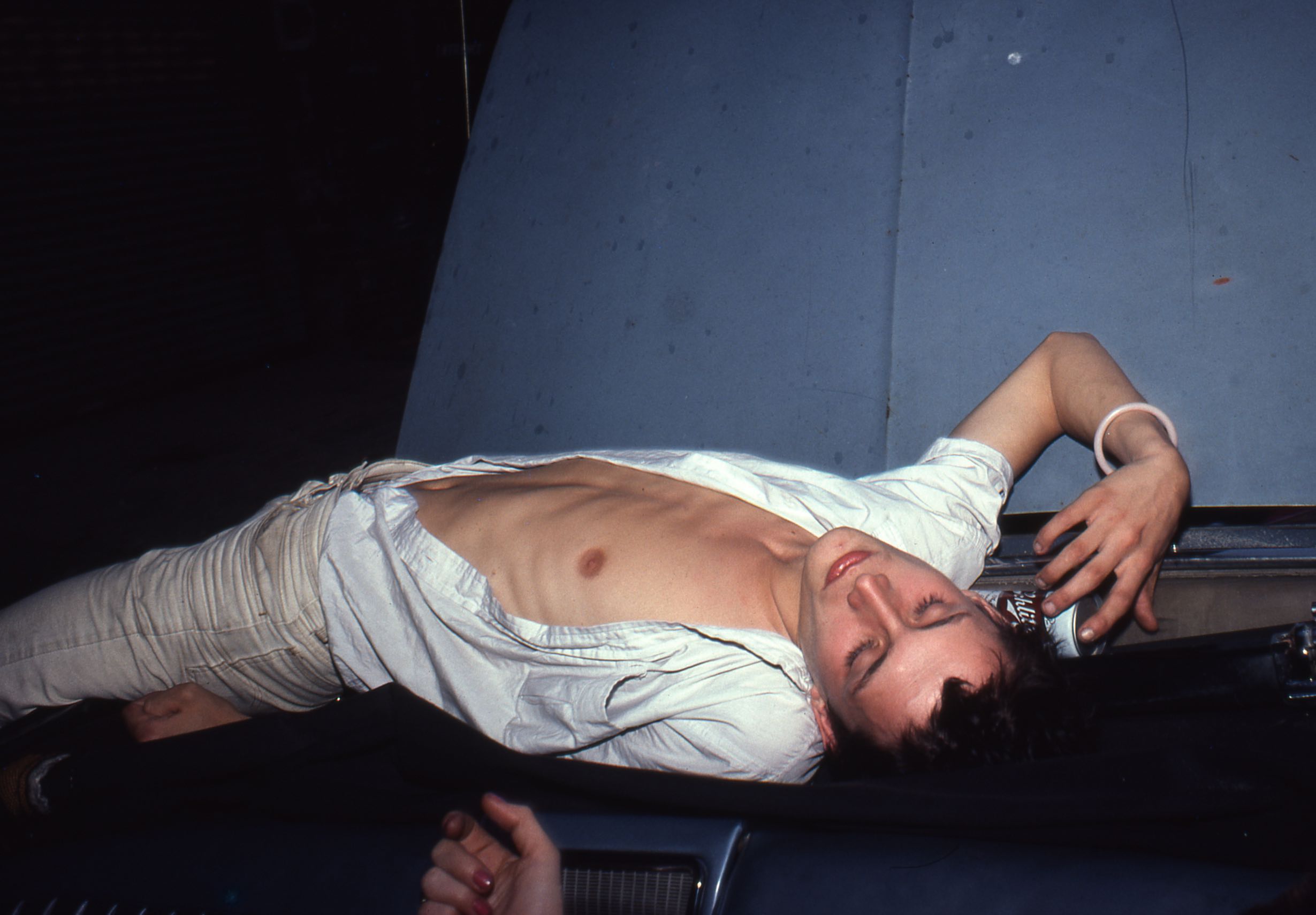

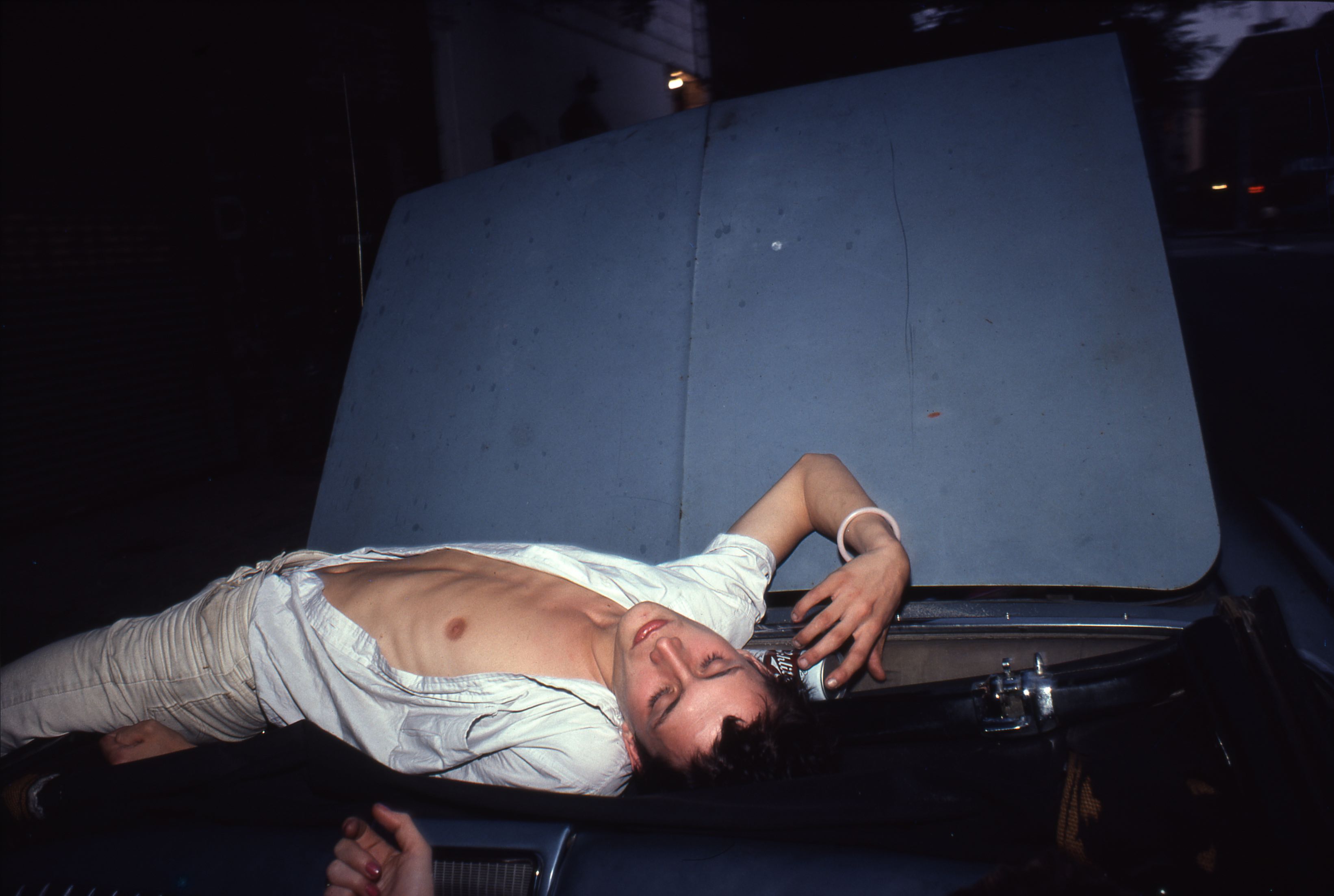

The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, the mythic photo series by Nan Goldin, is presented in Mexico for the first time. The project, which took around 35 years to complete, still resonates with the public. The precise and detailed record of Goldin’s life allows us to glimpse the dichotomy between autonomy and dependence, freedom and addiction. Perhaps what persists in the series is the struggle for understanding within intimacy, inside the different relationships that Goldin formed throughout her youth.

There are aspects of the series—domestic violence, for example—that are still performed in the current construction of the feminine and the masculine. The familiarity with which Goldin approaches the viewer is both obsessive and seductive. For 45 minutes, the American artist explores the social and gender paradigms of each moment, drawing from the emotional ties she forged from 1979 to 1986.

By presenting the series as a slideshow, the viewer moves into Goldin’s world (upon which they can project their fears and desires). The piece offers a tour of cities like Boston, New York, Berlin, and Mexico City, musicalized by Dionne Warwick, Nico, The Velvet Underground, and James Brown, among others. The Ballad illustrates the vibrant post-Stonewall LGBTQ+ community, the growing AIDS pandemic during the 80s, heroin addiction, the physical abuse that Goldin suffered during her tumultuous relationship, death, life, motherhood, and family.

The exhibition serves as an analysis of the current human condition. Sylvia Plath said that, “So many people are shut up tight inside themselves like boxes, yet they would open up, unfolding quite wonderfully, if only you were interested in them;” it is there that this work acquires its power and permanence.

The three exhibitions reflect the difficult reality faced by countless women around the world, and they also propose a comparative reading among themselves. Despite being projects that allude to a past time, they remain valid for the problems they reveal and for the questions they raise.

Unmissable, to say the least, these exhibitions at the Centro de la Imagen are a reminder of both the nonconformity that exists in Mexico and the country’s impetus for change. They constitute a celebration of talent, strength, gender diversity, and the human being’s ability to create alliances in the face of adversities that have arisen. Three projects that bring together a series of stories that persist beyond the exhibition space.

It’s going to fall!/¡Se va a caer!

Sexual freedom for all!/¡Libertad sexual para todes!

The shows will remain up until February 23rd, 2020.

* https://elephant.art/one-photographers-journey-brutal-world-illegal-abortion/

Published on December 19 2019