Review

Matador T-1000. Napoleón Aguilera at PALMA

by Marcela Roldán

Reading time

5 min

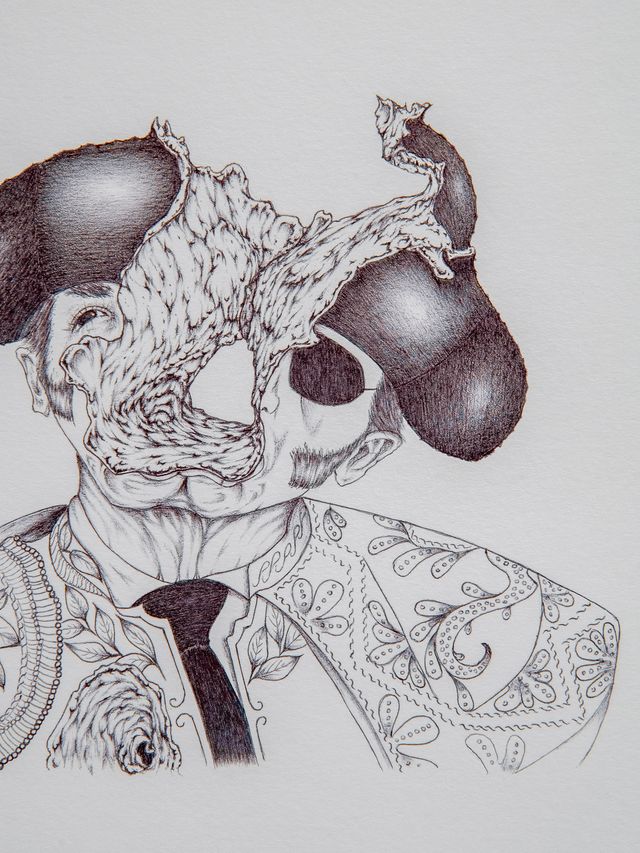

In his latest project Matador T-1000, hosted at PALMA, Napoleón Aguilera brings together two seemingly irreconcilable figures: Spanish bullfighter Juan José Padilla, marked by the loss of an eye in the ring, and the T-1000, the liquid villain from Terminator 2, condemned to fragment and endlessly reassemble. Both embody the same condition: wounds that never heal and matter that splits open only to reconfigure itself. From this, a haunting question emerges: how can one inhabit bodies that never scar over—liquid bodies that regenerate within a present shaped by violence?

In a game between parody and irony, Aguilera deploys humor throughout the exhibition. Yet this humor does not diminish the gravity of violence; instead, it enables a critical, playful look at popular culture, bullfighting symbols, and the influence of science fiction cinema—transforming irony into a conceptual tool to interrogate cultural inheritance and bodily fragility.

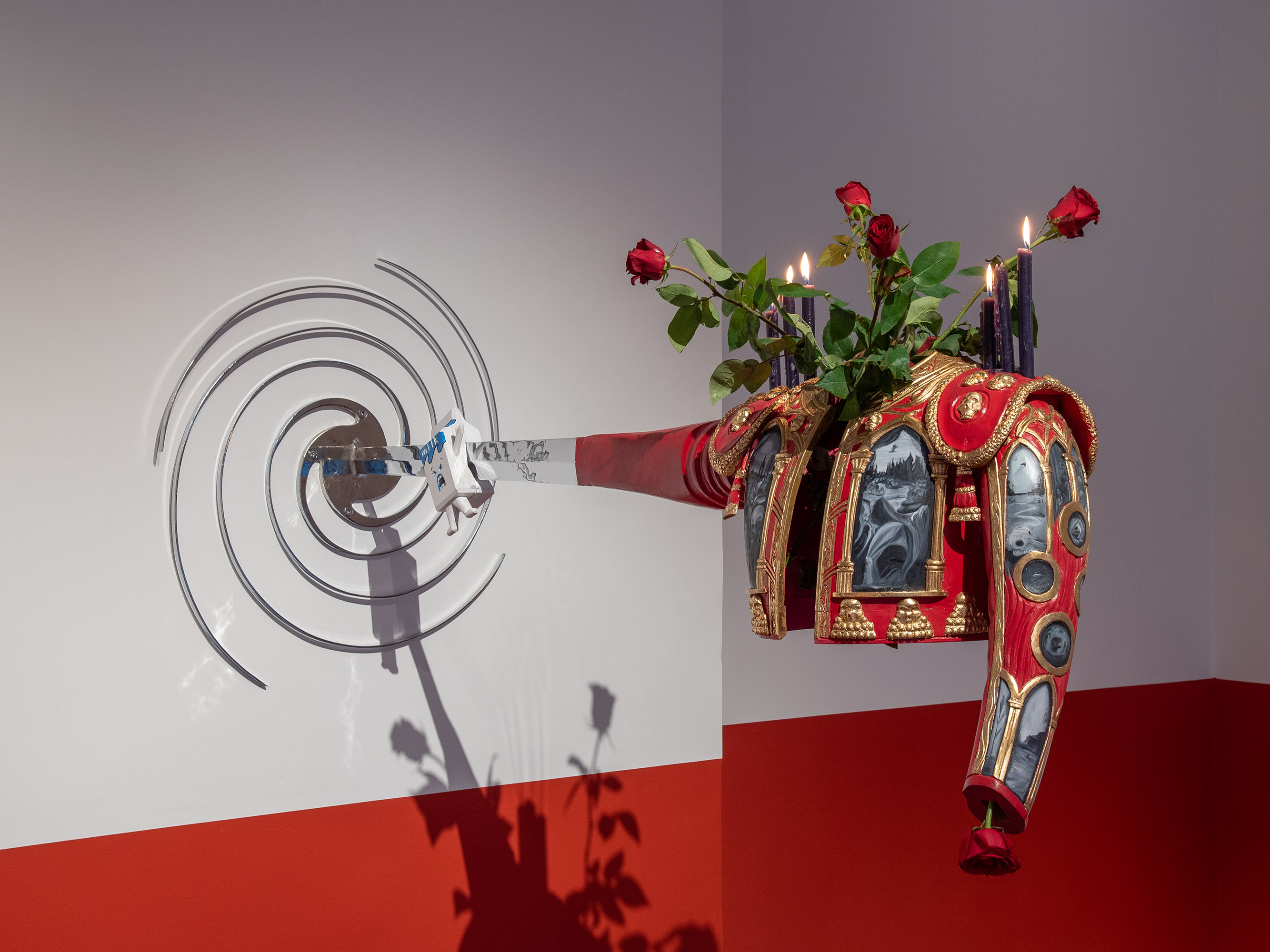

At the heart of the exhibition are four wooden bullfighter’s jackets: tercio de banderillas, tercio de varas, tercio de muerte, and orejas y rabo (trophies), all referencing the traditional stages of a bullfight. Suspended in the gallery, the jackets toy with the weight of their materials. By replacing the customary fabric with wood, Aguilera turns them into heavy, resistant objects, amplifying the idea of bodies that endure both violence and constant transformation. Their arms extend like weapons, evoking at once the movements of the matador and the iconic scenes of Terminator.

The jackets’ surfaces display fragments of a dystopian universe generated by artificial intelligence, but translated into oil painting by hand. Technology drafts the image, while the human gesture fixes it. Brushstroke, paint, and craft hold the digital in place.

Lit candles accompany the jackets, adding a symbolic layer: a metaphor for the “lights” of the bullfighter’s costume, but also a reminder of death’s inevitability. The suits of lights here become altars, recalling the Baroque tradition of vanitas: bodies that shine, burn out, and confront us with the inescapable.

Though posed in cyborg-like stances, the jackets’ density conveys another truth. These are bodies that resist and fracture—open portals to the indeterminate. They mark the infiltration of global culture into local traditions: what was once a symbol of Hispanic baroque has become a canvas for Hollywood imagery, questioning how identities are renegotiated in a world oversaturated with globalized images.

Two smaller sculptures expand the exhibition’s scope. A porta Gayola blends into the floor, born from Aguilera’s research and production within PALMA. Its discretion engages in dialogue with the architecture: rather than imposing, it silently echoes the gesture of the bullfighter unfurling the cape. The second sculpture, Cornada, presents a bullish body disfigured and wounded, yet in motion. Its gesture is not solemn but dynamic—almost dance-like. Unlike the rigidity of the jackets, this piece channels the ritual’s ebb and flow, as if the wound itself could become choreography. Here, bodily liquidity is not only metaphor but the very form of existence: constant movement, oscillating between destruction and regeneration.

Five drawings complete the exhibition, presenting Padilla’s wounds without mediation: torn flesh, violence that does not vanish. They remind us the body never closes. The T-1000 reconstitutes itself without pause, flowing as liquid metal; Padilla bears his irreversible wound. Between them, Aguilera invites us to reflect on contemporary bodies: fragmented, forced to reassemble within narratives that never reach closure.

Craft and digital coexist here. Hand-carved wood and oil painting translate AI-generated images; liquid metal becomes a manual gesture; Padilla’s wound turns into drawing, and the memory of the bullfighter into sculpture. The exhibition unfolds as a contemporary vanitas: bodies that shine, burn out, and remind us of death’s shadow. The darkness of Terminator 2—its devastated, mechanical future—resonates in these works; the same sense of inevitability and expiration permeates each piece.

Aguilera shifts our gaze: what could appear as a playful crossover between pop culture and bullfighting becomes an unsettling commentary on our relationship with damaged bodies. The jackets dazzle aesthetically, yet their conceptual weight goes further: they compel us to acknowledge that the wound is not an exception, but a permanent condition. The exhibition confronts us with a present without closure, where violence never ceases and memory never heals.

Each wound is an open portal to otherness, without promise of escape*, but also without possibility of denial. It returns us to the artist’s central question: what would a Terminator of our time look like? A body that dances through its fractures, a liquid body that never closes, or a collective body—pierced by violences—that endlessly recomposes without ever reaching redemption? The answer hovers in the space, like an open wound we are left to imagine.

The exhibition runs through September 6.

— Marcela Roldán

Translated to English by Byron Davies

*Fragments drawn from the curatorial text.

Published on Aug 22 2025