Article

The Eye’s Bodies: Calixto Ramírez

by Renard

Reading time

5 min

Calixto’s eye is full of dirt and without further ado he’s learned to see through that. Atop the armor of his intuition, the artist floods his head into the subsoil that he transports everywhere.

He stains the landscape with dust that succumbs to the air, just as a brushstroke does with the imagination by not being traced, and—although the dust falls—it returns to the ground and the stain disappears. Calixto plays with pictorial perpetuity because he knows that the terrain could only fade if time did as well.

He buries himself in order to become a horizon; he stands up in order to be a mast on which fly pagan flags of the territory of experience; he is willing to become a line and surrender to the insatiable task of being, at every second, a potential drawing.

When the eye commits itself to seeing (which is not the same as just serving its biological function), it swells and expands, bodies grow everywhere (including their own and that of things); distinguishing one from another is then at the service of relating to them. Under these conditions, painting is the art of observing the world and reacting to it. But what is knowing how to observe the world? In this case: it’s putting lime on the face.

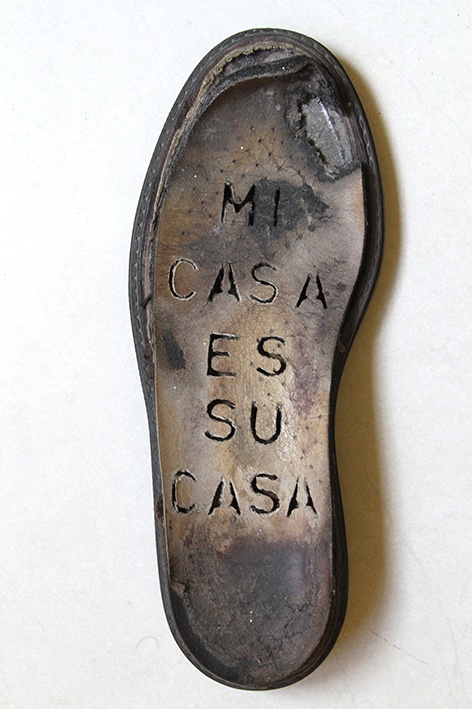

One should not underestimate the scope of painting as an eminent discipline in the face of the variety of media concerning us today, since the pictorial task does not begin or end on a canvas. It has never been like this, and long before any action painting or self-reflexive discourse about art there was already a painter walking miles with material on his back, waiting until he found the dignity to sit down to observe something: a painter looking in the mirror until she manages to appear, dust raised in front of a face that struggles to see, skies clouded by the gaze, suns that blind against understanding in favor of contemplation, paths traced by the worry of drawing something, and dirt spots on the soles. I have always admired Calixto’s filthy shoes, operating as a sign that he’s an artist, since although many of us appear caught up in our own heads, it should not be forgotten that with the swollen eye, the skull has feet and the feet a thought that forces us to walk through the expanse of a city or a desert: or else, like me, to make circles in a room with the windows closed.

Despite the tidiness of his framing and the straight lines anchoring him to a demanding aesthetic, Calixto is inevitably disorganized because otherwise he would not be able to talk about things with his eyes in his mouth; his work’s poetics lie in it. When he explains the origin of an image and its relationship with its surroundings, it is as if a piece of earth had risen up to speak through its cracks and narrate its experience as soil. For me there is no difference between the author and the work—but not because I think they’re the same thing, but rather because neither of them is delimited by their identity. Whether in a photograph, a sculpture, or Calixto himself leaning against a column smoking, I cannot help but notice the eye growing in each territory that his image occupies.

Subject, object, discourse, landscape… all of this is interchangeable when the aim is focused on the world and its perception is being aligned under the idea of the universe knowing itself, which alludes to reflections on quantum physics or contemporary cosmology. I could say that Calixto’s work makes me think that this is one of the infinite ways in which nature knows itself, in this case by means of an artist willing to become a branch, mountain, cement, or footprint.

All of this invites reflection on the captured images: the ephemeral ones or those that are constantly updated about the object. The disciplines are those that sometimes give us a guideline in order to know what type of image is being worked on—but is this really as important as the eye that experiences them? Although Calixto’s pieces sometimes make specific reference to painting and its history, on other occasions—where it could be assumed that such a note was not intentionally made and that there’s rather an interest in developing a conceptual, sociological, or geographic discourse—one can’t avoid noticing the pictorial event sustaining his work. I say this because I want to insist on the performativity of painting as well as on the pictorial nature of an action: qualities evident in the artist’s labor.

Just like on a canvas, in photos and videos I see the colors that he recognizes in what he sees, the amount of sky he allows into the picture. His brush body shaking or slightly operating, like a pictorial gesture on a plane, throws earth towards the earth, stains a wall of a wall, soil of soil, or rain of rain; purisms or tautologies that always reveal something moving about the space they inhabit.

Calixto is a line of the horizon with ribs, a vertical landscape that moves throughout his restlessness, insisting on ideas that when sublimated land even further, forcing the poem to be at the mercy of reality, inviting the eye and the world to become confused in order to see if they can fall in love.

When I cry upon seeing Calixto’s work it’s definitely because I’ve got dirt in my eye.

— Renard

Translated to English by Byron Davies

Cover picture: Calixto Ramírez, Pero yo ya no soy yo, ni mi casa es ya mi casa, 2015, Installation, rubble and sand, variable dimensions, photographic documentation. Courtesy of the artist

Published on April 6 2023