Review

Post-Luddite Artifacts. On 'Cándida' by María José Karaman

by Stefanía Acevedo

At El arenero

Reading time

5 min

On the night of November 4, 1811, not far from the village of Bulwell, four miles north of Nottingham, a small party of masked m̶e̶n̶ ̶p̶e̶r̶s̶o̶n̶s̶ gathers in the dark. They brandish maces and hammers, axes and pikes, and indeed some sabers and pistols. Walking in an orderly fashion, they head towards the residence of a manufacturer named Edward Hollingsworth. After posting a sentinel to monitor the neighbors’ reactions, they break down doors and shutters, forcing their way into the building. There they methodically destroy six wide frame looms before fading into the darkness. A little later, they meet again near the town in order to make sure that all the masked avengers have managed to escape.*1

If the Luddite uprisings that started among weavers at the beginning of the 19th century had managed to destroy all those machines that robbed them of their leisure time, and if their conspiracy against manufacturers had given rise to another kind of life, what other artifacts would have been created? What other materials, besides those produced and associated with gray factories like steel, polyurethane, aluminum, or fiberglass, would exist if they had some purpose other than utility? It is within these possibilities that we can imagine María José Karaman’s Cándida, in which we find the vestiges of a fictitious civilization where each piece presents a specific proposal of hybridization between materials, shapes, textures, and colors that stave off any prospect of application and efficiency. What would have happened if these machines and artifacts were not used for work but rather for recreational purposes?

Some slightly transparent white curtains welcome us into this strange factory where the anti-slip yellow vinyl linoleum floor recalls for us a feeling that is at once industrial and from childhood. The three walls in front of us are wine-colored, creating a contrast with the floor and with the seven pieces composing the exhibition. The ceiling, made up of a series of metal structures, shows that we are in the basement that has housed El Arenero for the past year.

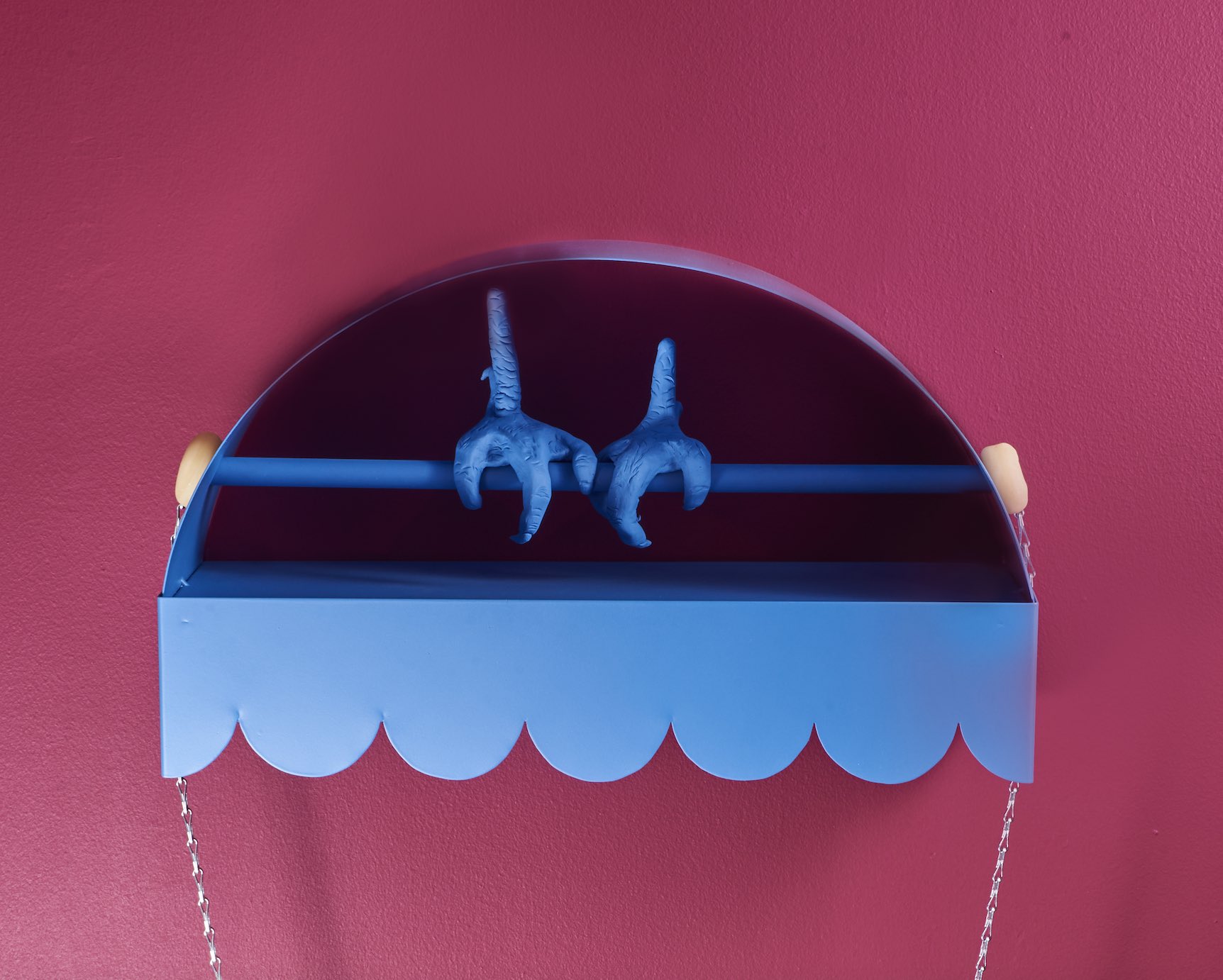

La tiendita de Chucho [Chucho’s Shop] draws attention for being the exhibition’s only monochrome piece, as well as the only one containing a sinister element: the legs of a bird that seem to have been attached to its base. At the same time, it sends us back to a kind of puppet theater or music machine like the one that appears in that film with a dancing chicken. A large steel chain hanging from one to another evokes a part of the cage where paradoxically nothing is imprisoned. Next to it is Caliente [Hot], a piece that combines such diverse materials as steel, polyurethane, and thumbtacks, all of them in different colors. The term giving the piece its Spanish name can be read within the texture of the polyurethane, where linear shadows can also be seen.

The piece Lavadero [Laundry] is a kind of stone photograph made using aluminum, steel, and polyurethane. The green frame contains a metal-colored grid with a circular cavity near one of its corners. Then we find a type of decorative object separated from the walls: Baila como trompo [Dance Like a Top] is a mostly dark thin metal bar rising up to 180 cm, with a baroque ornament covering it with organic shapes that could very well contain a word. In the lower part of this object a movement is concentrated, a chrome spinning top that does not stop turning, accompanied by a bulb emitting colored lights that likewise rotate constantly. In almost all the pieces the rivets are visible, evoking that feeling of manufactured items bearing their assembly processes.

Perhaps the most curious of the objects exhibited in this playful factory is Cándida, a plastic piece with curved contours similar to an industrially produced seat. It contains a small box in the center with a transparent opening that attracts attention, since it reveals that inside it houses pink crystals and a flower. In addition, it bears a steel tube intervened-on by a piece of wood, where one also finds handprints.

Finally, we encounter the last two pieces. No me sigan que voy perdido [Don’t follow me, I’m lost] shows a gradient going from blue to pink, with an embossed texture interrupted by a circle with glass where a red line peeks out. The other artifact is Goma cromática [Chromatic Rubber], a kind of electronic and manual device that seems to be made of stone, owing to its texture and color, when in fact it contains elements of fiberglass, stainless steel, polyurethane foam, and small rubber balls.

Etymologically the words “Luddite” and “ludic” are unrelated; nevertheless, I think that Karaman’s work links them together. The first word comes from the fictional character Ned Ludd, a standard-bearer for propagating the destruction of machines. Meanwhile “ludic” designates, via the Latin noun “ludus,” everything related to play, leisure, and entertainment. In this association, it could be said that Cándida brings together a desire to destroy machines in a jovial way—or, at least, to transform them into something allowing us to evade their historical relationship with work. Here we find artifacts that do not limit us to clock time, working hours, or linear time, but rather allow for another kind of temporal opening. Thus a dimension is unlocked, one where Luddites no longer gather in the dark in order to destroy machines, but rather have conquered a technical moment where materials are used for the pure exploration of their chromatic possibilities. Cándida allows us to imagine other machines, other possible artifacts, where industrial materials could have been used in a different way by a fictional civilization.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

*1: Translation of modified passage from Julius Van Daal, La cólera de Ludd [Ludd’s Anger] (Logroño: Pepitas de Calabaza, 2015 ), 100.

Published on June 30 2022