Review

Listening is relational. Lawrence Abu Hamdan at MUAC

by Sandra Sánchez

Reading time

5 min

This is the aesthetic work: your capacity to self-aestheticize,

not in the sense of beautification, but increasing your sensitivity to the world.

Eyal Weizman in conversation with Lawrence Abu Hamdan

Letting go.

45th Parallel (2022). A library between a border. People from both sides can meet as long as they return the same way they came in. Located on the 45th parallel, the Haskell Free Library & Opera House suspends the border and allows the flow between Quebec and Vermont. Migrants who are denied U.S. visas can meet their loved ones for a few hours. No big hamburgers nor big cokes, but a chance to talk, sheltered by books.

"It’s not only about sound; I’m listening to the way people listen. Or, I’m interested in the way people listen,"¹ says Lawrence Abu Hamdan, an artist whose solo exhibition, Crímenes Transfronterizos, is on through March 17 at the Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC). Lawrence is in conversation with Eyal Weizman, with whom he has collaborated from Forensic Architecture, a multidisciplinary research group based at Goldsmiths, University of London, that uses architectural and technological techniques to investigate cases of state violence and human rights violations in different global latitudes. The results of the studies are frequently condensed into creative works as well as data that has been used in legal proceedings by international courts.

See beyond the walls (muography).

"Sound is indivisible from the space in which it resonates. It is relational..."² Listening and overcoming the temptation to stop after locating the message, decoding it and responding or discarding it. Listening to the space around what is heard transforms listening from something limited to what the ear can perceive into an active process of attending to reality. Listening produces space.

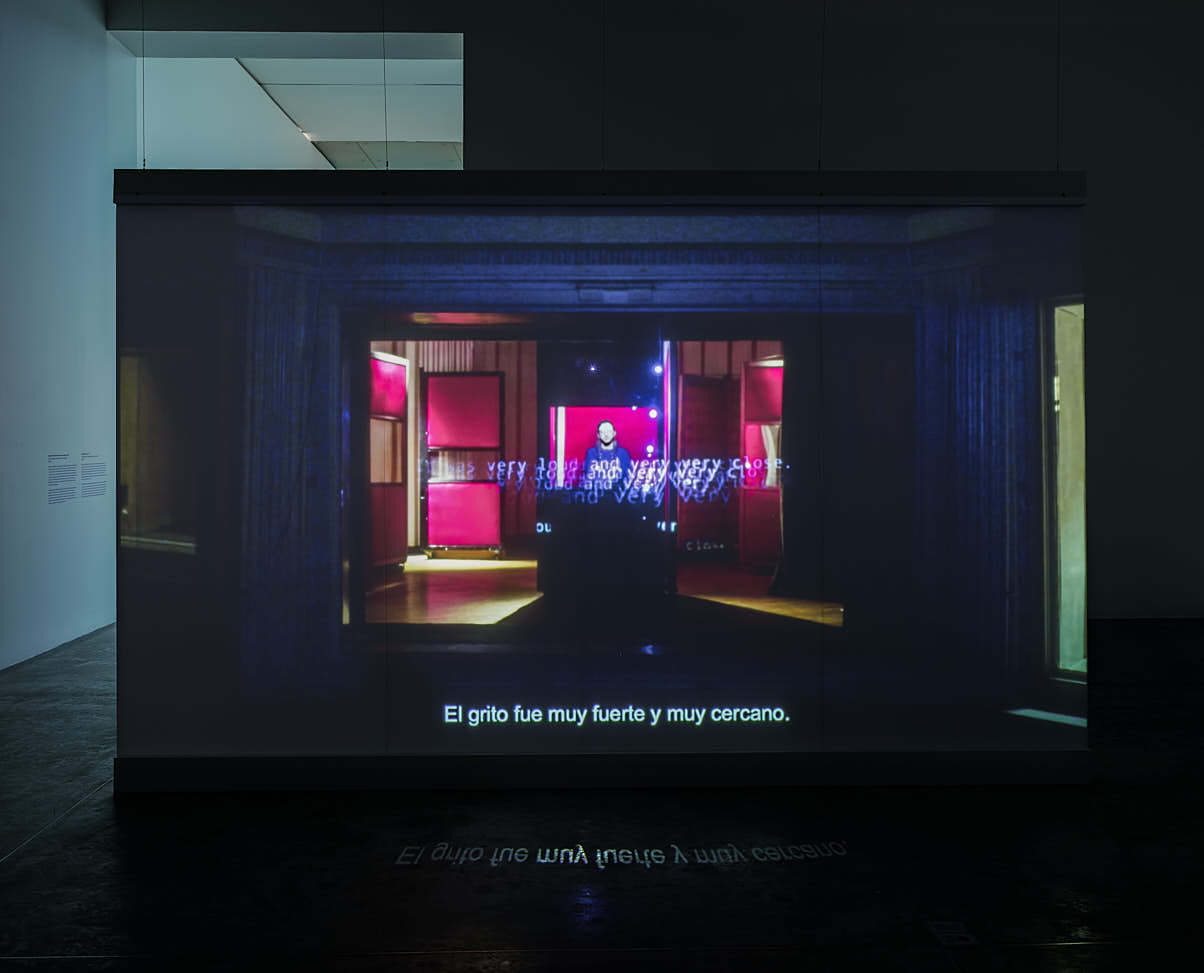

Walled Unwalled (2018).

- The decision favors the home-based dealer since the heated walls that gave him away are private property.

- “The murder that athlete Oscar Pistorius committed against his girlfriend, Reeva Steenkamp, in the bathroom of the house. Pistorius was convicted after it was found that the bathroom wall he shot at amplified the sound–rather than muffling it, as he claimed–and therefore he could have distinguished his girlfriend's scream behind the wall.

- Finally, the video addresses the acoustics in prisons and, in particular, in the Syrian torture prison of Saydnaya. The prisoners were always blindfolded, so that the world of sound was their only means of relating to their environment and of survival during the time of their detention. Abu Hamdan asked the prisoners to describe the architecture of the space where they had been imprisoned. However, it was their perception of sounds that made it possible to discover the conditions of torture and suffering to which they were subjected."³

Sonic image.

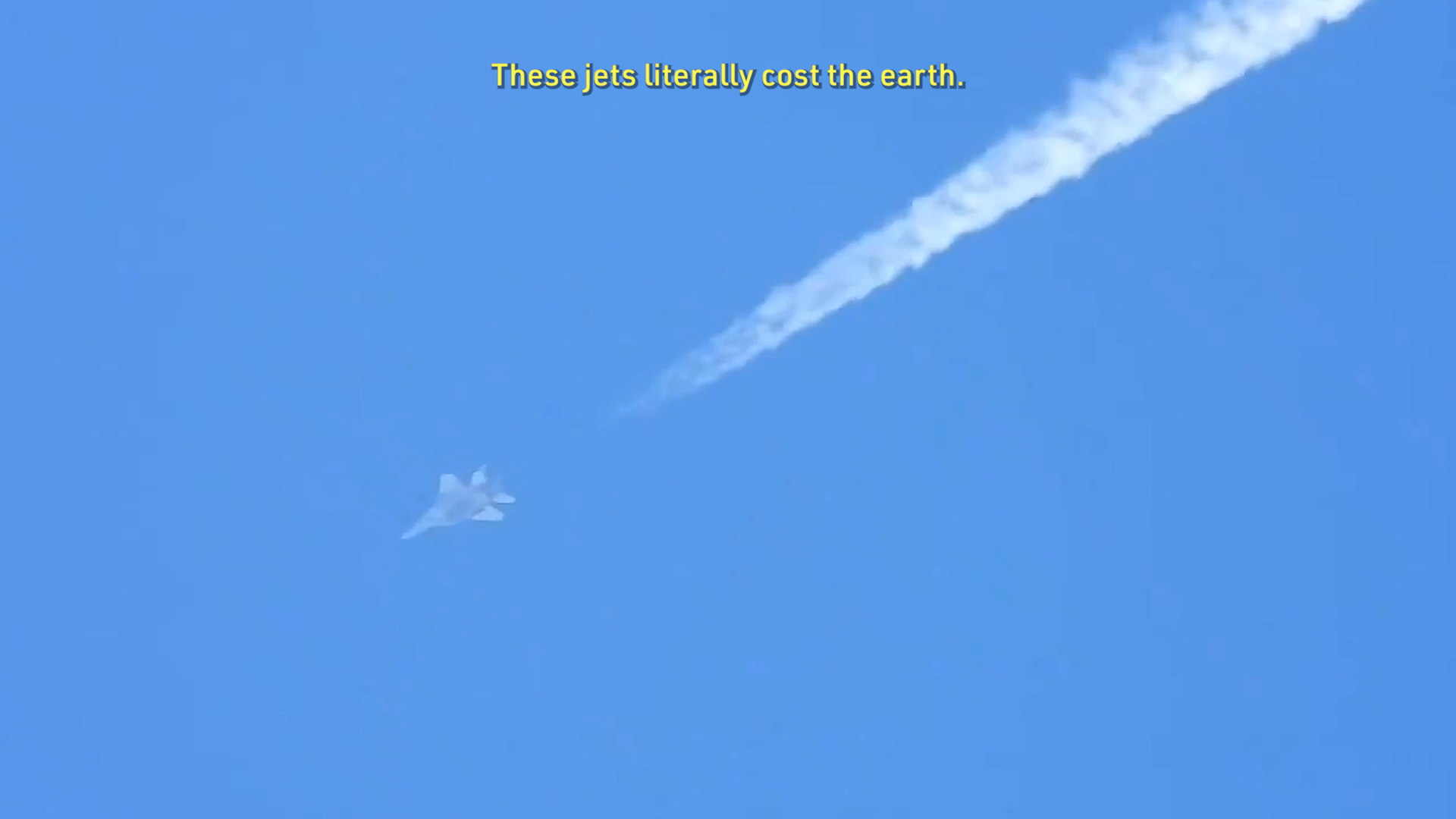

An explosion. The search for a cause, planes flying over Beirut. To listen is to construct a signifying chain, hence its possibility of critique, of dismantling, of making other signifying chains.

"On August 4, 2020, 2750 tons of ammonium nitrate exploded in a warehouse in Beirut's main port, one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history, resulting in thousands of displaced, injured and hundreds of dead. Abu Hamdan found that there were no Israeli planes flying at the time of the explosion. However, it was the beginning of an exhaustive investigation that revealed the constant encroachments that Israeli fighter aircraft had made into Lebanese airspace over more than 15 years."⁴

Lawrence Abu Hamdan describes the sonic image as one whose "individual value or truth value is derived not from a single source, but from its relational qualities. It is not a visualization of sound."⁵ A sound that produces images that were not there before, but were there: the power to relate. It is no longer about people, actions and objects, but about situations, scenarios, staging, where one variable is inscribed from the others.

The Diary of a Sky (2023) where attendees are required to lie down on pillows and gaze up at the video on the ceiling, which depicts "the repercussion of the persistent noise of airplanes and the anxiety that a possible bombing produces in the citizens. These air raids have been part of the daily life of the inhabitants of Lebanon [...] The piece is made up of images of the sky obtained by the inhabitants of the city with their cell phones. It is archival material found online that shows new forms of testimony where, beyond the first person, the witness becomes collective".⁶

It is not about listening to something new. Hamdan's work suggests listening to what is already there, paying attention to sound as a biopolitics to understand its control mechanisms, and proposing alternative choreographies of reading and rewriting that which violates us and is frequently justified by the law, all from an aesthetic linked to proprioception rather than to the hierarchical ordering of sensations. This is far from the modern politics of a differential that will finally succeed in establishing a utopian moment. Apart from the political significance of these pieces, it is noteworthy to honor the artist's staging efforts, since he employs theatrical and performance techniques to convey his findings to the audience; a listening courtesy that showcases its own creation in its presentation.

Translated to English by Luis Sokol

¹ Lawrence Abu Hamdan. Video of virtual tour with the artist and curator Virginia Roy. Accessed January 19, 2024 https://muac.unam.mx/exposicion/lawrence-abu-hamdan

² Ibid.

³Virginia Roy Luzarraga. “Fugas acústicas y muros de escucha” by Lawrence Abu Hamdan. Crímenes transfronterizos. UNAM, México, 2023. p.11.

⁴ Ibid. p. 14.

⁵ bid. p. 15.

⁶ Ibidem.

Published on January 28 2024